'It's long overdue:' After T.I.'s controversial 'hymengate,' NY lawmakers hope to ban 'virginity testing'

When Cassandra Corrado, 27, remembers lying back on a medical examination table with her feet in stirrups and legs wide open for a pelvic exam with her family doctor at the age of 15, she can still recall how vulnerable and uncomfortable she felt. But what she says “haunts” her about one particular exam is when the physician oversaw a “hymen check” to — according to him— confirm that she was still a virgin.

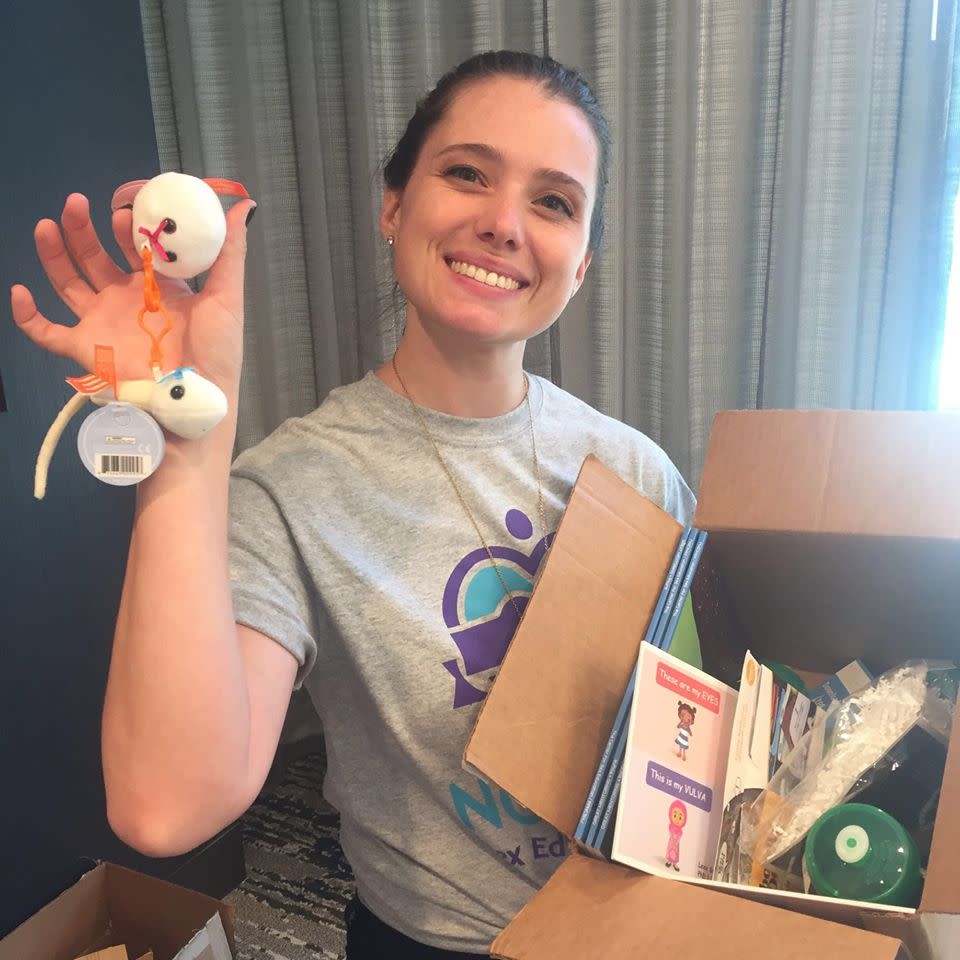

“I felt violated and I felt ashamed,” Corrado, now a sex educator, tells Yahoo Lifestyle. “My mom didn't ask to have this done, it was just my doctor kind of putting in this judgment call on my virginity.”

Until rapper T.I. revealed that he attends his 18-year-old daughter’s gynecologist appointments to make sure she’s still a virgin, it was hard for some to imagine the largely debunked “virginity tests” being performed in accredited hospitals and clinics across the country. His admission ignited public outcry and revealed the prevalence of the seemingly antiquated practice that continues with little oversight.

But that might be changing — at least in New York.

As of this week, lawmakers are trying to enact a bill that would ban the practice altogether. If passed, it would become the first piece of legislation to do so on the state and federal level. New York Assemblywoman Michaelle Solages, who drafted and introduced the bill, says it’s “long overdue.”

“Virginity tests always seemed like a faraway idea that [happened] in other countries, in other places… But it’s happening,” Solages tells Yahoo Lifestyle, who was “outraged” when T.I. made headlines. “So I submitted legislation on the state level to ban the practice of virginity exams, and also prevent doctors from engaging in this unscientific, nonclinical practice.”

A ‘Virginity Exam’ does not exist

For years, doctors and clinicians have been performing “virginity tests” by checking to see if a woman’s hymen, a thin membrane that partially covers the entrance to the vagina, is still intact. However, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the “presence or absence of a hymen does not indicate ‘virginity’” as the hymen can be torn or stretched by many activities aside from sexual intercourse including tampon use, playing sports and other medical procedures.

“A ‘virginity exam’ does not exist,” says Maura Quinlan, MD, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University and legislative chair for the Illinois section of ACOG. “It’s a myth that any type of medical exam can prove if a woman is a virgin.”

In a statement, the ACOG says they do not have guidance on “virginity tests” because they only offer it for “medically indicated and valid procedures.” In 2018, the World Health Organization called for the elimination of the practice, arguing that "virginity exams" are a "violation of the human rights of women and girls" that have "no scientific or clinical basis."

Although it is nearly impossible to track the prevalence of these exams, in a 2016 survey of honor-related practices among nearly 300 U.S. obstetricians and gynecologists, 10 percent said they performed care on patients who requested “virginity testing” while five percent agreed to perform “virginity restoration,” or the surgical restoration of the hymen.

Beyond the fact that “hymen checks” have no scientific or medical basis, the practice can have long-lasting impacts on women. For Corrado, it’s an experience that she says “haunts me 11 years later.”

"I felt violated and ashamed"

Since the age of 12, Corrado’s mother had always told her daughter that she could go on birth control when she was ready. That day came at age 15 for Corrado who, at the time, had just started having sex with a boyfriend she’d been dating for a while.

Her mother, who had never gone to a gynecologist, later scheduled her daughter an appointment to get birth control with the family’s physician, a male general practitioner. Sensing Corrado’s discomfort with a man performing her pelvic exam, which is not medically necessary to receive the prescription, the doctor had a female medical school intern perform the exam instead, while he stood by and oversaw the procedure.

“I was uncomfortable to start with — and even though the intern was doing the exam, he was standing right behind her,” Corrado says. “I felt like I was more comfortable with him doing the exam because I would have felt more protected. But instead, he could see my whole body at once.”

Despite her discomfort, the exam was done without cause for concern until her doctor asked an unprompted question that she says made her feel “judged” and “violated.”

“He kind of leans down to her and says, ‘Is she still closed?’” Corrado recalls. “What he meant was, ‘Is her hymen intact? Is her hymen still undisturbed?’” With her mother sitting behind her she froze, worried her mother would discover she had lied about already having sex. Fortunately, the intern chose to confirm that Corrado was still a virgin. In response, the doctor nodded his head and said, “Good girl,” a remark that “stuck” with Corrado, and echoed a larger societal notion that a woman’s worth and value are hinged on her “purity” or virginity.

“Well, okay, if I'm a good girl because you think I'm not having sex and I am having sex, what does that mean for who I am?” Corrado recalls thinking at the time. She adds that as a high-performing and actively involved student, she was indeed, in the traditional definition of the term, a “good girl.”

For Corrado, this single traumatic experience had irrevocable and life-long consequences on her relationship with doctors and her own body.

“I felt violated and I felt ashamed as someone who was having sex. I felt like I couldn't talk about it. Because of that, I felt like I could never talk to my doctor or my parents about having sex,” Corrado tells Yahoo Lifestyle.

To this day, she gets nauseous driving to her gynecologist appointment and is often wary of physicians. But even worse than losing trust in her doctors, she felt any sexual intercourse she had throughout high school felt “shrouded in shame,” making it difficult for her to advocate for herself in sexual situations.

“That experience took that [ability] away from me. I didn't feel comfortable having that autonomy afterward,” Corrado says.

In response to T.I.’s revelation, Corrado revealed that her experience with her doctor made her feel “dirty, bad, and wrong.” Now, Assemblywoman Solages is working to make sure doctors and any other medical professionals don’t make other young women feel the same way.

Virginity exams "violate the rights of women"

On Nov. 8, Solages introduced the bill in response to the incendiary comments made by T.I. in the hopes of altogether banning New York State “virginity tests” — or exams in which two fingers or a speculum are inserted into the vagina in search of the hymen or to measure the elasticity of the vaginal wall.

The proposed bill states that “any licensed medical practitioner who performs or supervises a virginity examination” could face professional penalties such as losing their medical license. If a clinician performs or supervises a virginity examination in a “non-medical” setting, they could be charged for sexual abuse in the first degree. For those who may believe this punishment may be extreme, Solages argues that these “virginity tests” are yet another “component of sexual violence against women” and is often “humiliating,” “traumatic” and “often painful.”

She and other co-sponsors of the bill argue that the “unnecessary” practice “violates the rights of women and reinforces stereotyped notions of female sexuality.” Solages adds that the bill is all about ensuring that “women are given basic respect.”

Corrado, who currently lives in Florida and teaches sex education to adults 18 and older, echoes the larger impact of “policing” a woman’s virginity, having experienced and witnessed first-hand the detrimental and traumatizing impact virginity standards can have on young adults.

“Virginity is a social construct,” Corrado tells Yahoo Lifestyle, referring to the idea of virginity, and sex itself, having different meanings to different people, particularly when various sexualities are taken into account. “When you are upholding such strict standards of what it means to have sex, you're [confusing] them about their bodies. You’re telling them that their bodies aren't theirs and that they don't have autonomy over them. You're telling them that anything they're doing with them should be kept in secret because to be sexual is to be shameful — and none of those things are true.”

When she first read the headlines revealing T.I. forced his daughter, Deyjah, to undergo a “virginity test,” Corrado says her “blood was boiling.” Outraged, the news prompted her to write an op-ed for online blog SheKnows detailing her experience with an open letter to the rapper and her former physician warning about the potential “trauma” and damage they could be having on a child’s self-worth.

“One day, your child will probably have sex. And if you spent years policing them about their purity, you will be haunting them,” Corrado wrote. “When I am a parent, I want my children to grow up and know that they are worthy. That they are lovable. That they are not used up, cast aside, wasted, once they’ve had sex. When I am a parent, I want my children to feel safe going to the doctor.”

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

? 3 STDs have skyrocketed in the U.S., new CDC report says — here’s what you need to know

? Record-high STD rates in Hawaii linked to online dating — why apps may be making sex less safe

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.