'Americanized: Rebel Without a Green Card' author, on growing up undocumented: 'We tried to do everything right'

For someone who spent nearly two decades concealing her identity as an undocumented immigrant, Sara Saedi is remarkably forthcoming. “I feel so envious of people who speak Farsi perfectly,” she tells me via phone from Los Angeles, where she’s busy promoting her new book, Americanized: Rebel Without a Green Card. “I have an American accent when I speak it — and it’s thick.”

Saedi is now a U.S. citizen, but the journey to get here wasn’t easy. The 37-year-old was born in Tehran at the start of the Iran-Iraq war, prompting her family to flee to San Francisco. Only 2 years old at the time they arrived, Saedi was unaware that they’d overstayed their visitor visas until her teens, when an older sister spilled the beans. “She told me we were ‘illegal’ — which was the term more commonly used then,” says Saedi. “It was a very scary word to hear at 13.”

The realization that she was undocumented shook Saedi to her core, bringing fears of deportation and an internal battle over her identity — both of which she had to keep secret from friends. It would be another seven years — and 18 total since their arrival in America — until green cards were finally within reach. It was a long, sometimes terrifying journey that even her closest friends were unaware of.

But that was then.

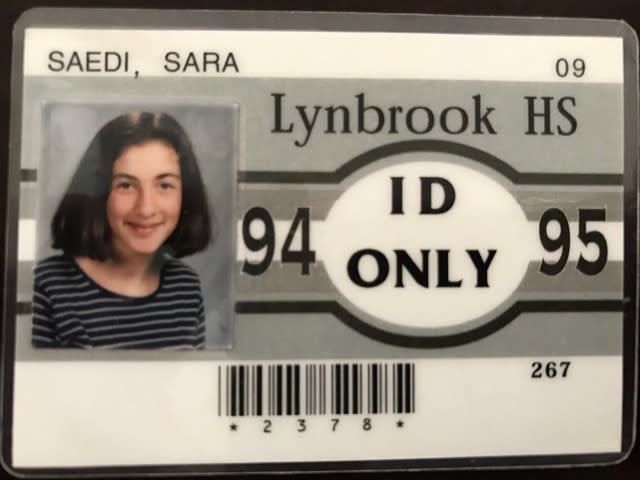

Now a novelist, TV writer, and mother of a 17-month old son, Saedi looks back on that time with humor in her book — weaving diary entries and photos into clever commentary on life as an immigrant. While the details of her story are unique, the overall narrative is not. There are an estimated 3.6 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. Their stories are — increasingly — the American one.

Yahoo Lifestyle: You were born in Tehran, Iran, in 1980 before moving to San Francisco at age 2. In the biography from one of your earlier books, The Lost Kids, it says you literally “entered the world to the sounds of bombs exploding near the hospital.” Is that surreal to imagine now?

Sara Saedi: Yeah, it’s very surreal. My mom’s labor had to be induced because they were worried about her going into labor at a time when she wouldn’t physically have been able to get to the hospital. So it was a special delivery, literally sped up because my country was at war. It gives me perspective on things today.

You mention in the book that you don’t remember Iran. What were your first memories of America?

I have a lot of memories of adjusting culturally — of assimilating. I remember being in preschool or kindergarten, and for me, it was very commonplace that when you greeted somebody you kissed them on each cheek. But I remember picking up on the fact that my 5-year-old friends were very uncomfortable with it and telling my mom like, ‘I don’t understand, the other kids don’t seem to like it.’ And she had to explain to me, ‘Oh, in America you can give them a hug, but people aren’t used to kissing their friends on the cheek.’ My cultural touchstone was everything that was going on within my own household, but I had to shift that behavior when I left.

You went to a diverse school where there were other Iranian immigrants. But it wasn’t until age 13 that you learned about being undocumented. What was that like?

I remember my sister was filling out job applications and was really frustrated because they all wanted a Social Security number. She said, ‘Yeah, we don’t have Social Security numbers, we live in the country illegally and we could get deported at any time.’ I had no idea. I knew I was a citizen of Iran, but I didn’t know there was other legal paperwork that we needed in order to live in the country. So it was a huge shock. And the fear of getting deported — to think that I could suddenly be forced to live in a country that I wasn’t familiar with — that was very scary.

Do you think that fear hindered your ability to be a normal teenager?

I think it definitely hindered my ability. As a teenager you’re so used to having girlfriends who you tell everything to, so it’s definitely weird keeping a part of yourself secret. That was always a challenge. But even just being an immigrant and being raised by immigrants made me feel more awkward. I was very cognizant of the things that seemed different about me, or different about my family, compared to some of my friends.

Like the fact that you had a unibrow? You mentioned in the book how a boy in grade school pointed this out, in a mocking way, which ultimately convinced you to tweeze it.

Yes, exactly.

But now they’re back — unibrows! In the fashion world.

Wait, really? I don’t believe you.

I promise you.

Well in that case, maybe I’ll have to stop tweezing mine! [Laughter]

In all seriousness, how did you overcome all of these things — managing to keep this secret, marrying your two identities of being Iranian and American? It seems like a lot for a teenager.

I really give a lot of credit to my parents. I think once I confronted them [about being undocumented], they were very adamant that nothing was going to happen and that everything was going to work out. They told me that we weren’t going to get deported — and even though they didn’t know whether that was true or not, they knew they needed to make it a priority for us to feel like we were safe and that our status was stable even though it really wasn’t. So it was definitely always a fear and anxiety in the back of my mind, but I think that my parents tried to always make us feel like everything was going to be OK. If they were more reactionary, or if they had a harder time basically disguising their own fears and anxieties about it, then I think I would have been much more worried as a kid.

Something you also touch on in the book — and that other immigrants have too — is this sensation that sometimes it feels like you’re living a double life. Do you still feel that now?

It is something that I feel as an adult, particularly now that I’m raising a child. I don’t look very Iranian and [my son] looks even less so — I don’t think anyone would look at him and know that he was half Iranian. So there’s that part of me that really, really wants to teach him to speak Farsi and to try and raise him with some of the cultural touchstones that I was raised with, so that he will feel comfortable also identifying with being Iranian. I don’t know if I’d say I’m leading a double life necessarily, but sometimes I feel like a little bit of an outsider with the Iranian community.

That’s really interesting. You’re trying to straddle these two worlds, essentially.

Exactly. Especially in writing this book — so much of which is about being raised by Iranian parents — there was a little part of me that was like, ‘Oh, but if I’m too American, am I a fraud for writing about this?’ But I would imagine that’s something that’s normal among immigrants, that you are always comparing yourself to other people in your culture and always worrying that you’re letting go of too much of what you were raised with.

It seems like there is a lot of concern too about making your parents proud. In the book you called this “Immigrant Child Guilt Complex.” How did your case of “ICGC” inform who you are today?

[Laughter] It’s not like a scientific term; it’s something I made up. But I do think it’s informed my work ethic in a lot of ways. Growing up, it was just really obvious to me how much my parents sacrificed in hopes of giving us a better life, so it felt like the worst thing I could do was not make good on my side of the bargain. They never made us feel guilty, but we were just very aware of the fact that they completely uprooted themselves for us. So I’ve always wanted to be successful as an adult and do well because I never wanted them to feel like they brought us out here and we didn’t do anything.

I think that’s definitely relatable to a lot of people. So as a former undocumented immigrant, what do you want undocumented immigrants reading this to know?

Well, I know it’s a very scary thing to be undocumented, and the best advice I can give is there is a light at the end of the tunnel for many people. But until then, there are certain rights that undocumented immigrants have that I think they either don’t know about or they’re just so afraid in that moment and they feel like they need to comply. But I think it’s really important for people who are undocumented to educate themselves, and there are lots of great resources for that online.

But now as an American citizen, living in a city with many undocumented immigrants, what do you want these communities to know?

A large part of the reason I wrote the book is that I felt like a lot of people didn’t know how complicated the immigration process is in this country — or how long it can take. I really wanted people to know that we once we got here, we really tried to do everything right. And the system didn’t help us in a lot of ways. It took 18 years for us to get green cards and another six years to become a citizen. It isn’t just the length of time, it’s also a very expensive process: application fees, lawyers. I think maybe once people see how much undocumented immigrants are struggling to become naturalized citizens, that’s where the empathy comes in. Not only are they trying to live here legally but in the meantime most of them — like my family — are paying taxes. They’re really really trying — and it isn’t easy.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

The woman who wouldn’t back down to Donald Trump: Sally Yates

Beauty influencer: I don’t want to be the ‘token’ black girl

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.