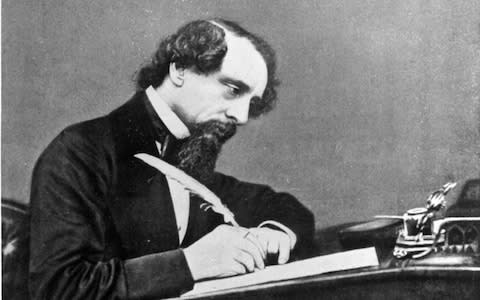

‘Bah! Humbug!’: How Charles Dickens grew sick of Christmas

“Mr Dickens stirs the gravy,” reported a rapt member of the audience at a reading of A Christmas Carol by the author in December 1867. The auditorium was packed; the queue for tickets half a mile long. “[He] mashes the potatoes with something of Master Peter’s ‘incredible vigour’, dusts the hot plates as Martha did, and makes a face of infinite wonderment and exultation when shouting, in the piping tones of the two youngest Cratchits, ‘There’s such a goose, Martha!’”

A Christmas Carol, concerning the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge and his conversion to Yuletide generosity, was 24 years old by the time this particular performance took place – and a firm fixture on the British Christmas circuit. The novel, with its beautiful illustrations by John Leech, had flown from booksellers’ shelves when it first came out on December 19 1843 – its entire print run of 6,000 copies gone by Christmas Eve.

Later holiday editions sold at the same remarkable rate. It was, said one contemporary commentator, “a national benefit”. Another called it a “an institution” and indeed, the Carol, as it’s known by its devotees, has haunted us ever since. It remains the most filmed and television-adapted of all Charles Dickens’s works. There’s yet another version coming to the BBC this Christmas, starring Guy Pearce and produced by Tom Hardy – though it’s hard to imagine it knocking A Muppet Christmas Carol off its perch.

It’s a surprise to learn, then, that by the time Dickens was standing on that gaslit stage in 1867, he had developed a Scrooge-like aversion to Christmas, adopting a position sympathetic to the curmudgeonly character who calls for “every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips” to be “boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart”.

“I fear I am sick of the thing,” Dickens wrote in 1868 to his close friend, the journalist and editor William Henry Wills, in a letter featured in a new exhibition at the Charles Dickens Museum. To the actor Charles Fechter, he wrote later the same year: “I feel as if I had murdered the ghost of… Christmas… years ago (perhaps I did!) and its ghost perpetually haunted me.”

Dickens is often credited with inventing Christmas as we know it. In truth, as the exhibition – Beautiful Books: Dickens and the Business of Christmas – makes clear, he was fanning an already healthy flame. “When he wrote the Carol, he was buying into a growing interest,” explains the exhibition’s curator, Louisa Price. She shows me a Christmas envelope – a piece of novelty stationery decorated with drawings of gift-giving, plum puddings and other traditions that the Carol is often wrongly said to have inaugurated – that actually predates the book by three years. “He was always commercially responsive,” Price adds. “He saw an opportunity and grabbed hold of it with both hands.”

As early as the 1820s, there had been a market for “gift books” – prettily illustrated annuals of poetry and short stories bound in red silk with gilt-edged pages that came out in December, for the Christmas market. Forget Me Not and The Keepsake were two of the most successful. (Indeed, in George Eliot’s 1872 novel Middlemarch, Ned Plymdale, “one of the good matches in Middlemarch, though not one of its leading minds”, uses a Keepsake to try to woo the beautiful but shallow Rosamond Vincy.) Dickens, along with other serious writers of the day such as Byron and Mary Shelley, would contribute pieces to these gift books. In 1835, he wrote a Christmas-themed essay, brimming with goodwill, for the weekly newspaper Bell’s Life in London. “Would that Christmas lasted the whole year through (as it ought)!” he writes.

Dickens’s relish for the season can be traced back to his grandparents, who were servants at Crewe Hall, a stately home in Cheshire renowned for its Christmas festivities. Later, Dickens’s father John would stage lively plays for the immediate family each Christmas, a tradition Dickens himself would continue, putting on his own theatrical performances – along with a Boxing Day cricket match – for friends and family at Gad’s Hill, his country house in Kent. Dickens’s daughter, Mamie, recalled that the entire household “looked forward to [Christmas] with eagerness and delight, and to my father it was a time dearer than any part of the year”.

Until he wrote A Christmas Carol, Dickens had tended to publish his books in serial, “and with good reason. It had really worked for him,” says Price. “But when he conceived of the Carol, he wanted a book that people could gift: something that was compact and really beautiful. He put his heart and soul into it.” Dickens wanted, he told his publishers, “brown-salmon fine-ribbed cloth, blocked in blind and gold on front; in gold on the spine… all edges gilt”. The illustrations, he stipulated, should be hand-coloured. He then changed his mind about those colours and about the colour of the endpapers, and the frontispiece, too. On one of Leech’s sketches for Fezziwig’s ball, Dickens scrawled, “this is not what I thought!!” Differing trial editions of the book form part of the exhibition.

The result was a book that made far less profit for Dickens than he had hoped – just over £100, when he had envisioned something nearer £1,000. “He was bitterly disappointed,” Price says, adding that, for later editions of the Carol, and for the four other Christmas stories that he would go on to write – The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846) and The Haunted Man (1848) – the author settled for black and white illustrations, even camping out at his printers while they were producing the books, to prevent any costly mistakes.

From 1850, when he started his journal Household Words, he switched to producing a special Christmas issue full of short “fireside” stories, including pieces by other writers (Wilkie Collins and Elizabeth Gaskell, for instance), which eased his seasonal burden somewhat, though not entirely. “I have invented so many of these Christmas nos.,” he explained to Wills, “and they are so profoundly unsatisfactory.” He added: “I can see nothing with my mind’s eye which would do otherwise than reproduce the old string of old stories in the old inappropriate bungling way, which every other publication imitates to death.”

The market for Christmas books had quickly become saturated. One contemporary newspaper noted that, “regularly as the year draws to a close we are inundated with a peculiar class of books which are supposed to be appropriate to the goodwill and joviality of the season. Most of these publications are quickly forgotten; and indeed are so full of display that they deserve no better fate”.

For further indications that Dickens’s Christmas cheer had begun to curdle, we need only look to his bleaker, later writings. In Great Expectations (1861), Pip’s Christmas consists of a terrifying encounter with an escaped convict, being forced into stealing food, followed by an excruciating Christmas dinner in which he is near-paralysed by fear of discovery. In The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), Drood’s disappearance, on which the novel turns, takes place on a miserable Christmas Eve, marked with decorations and festivities described as tawdry and tired. In The Uncommercial Traveller Dickens even writes an account of a Christmas Day spent visiting a morgue.

His mood, at this late stage of his life, can be gleaned from a letter sent in 1869 – the year before he died – after a turkey that was coming to him by train had failed to reach him by Christmas Eve.

“WHERE

IS

THAT

TURKEY?

IT

HAS

NOT

ARRIVED

!!!!!!!!!!!” he wrote to the theatre manager George Dolby, supposedly a friend. He might as well have signed off “Bah! Humbug!”

What Dickens was still doing, of course (though some say it sent him to an early grave) was performing the Carol. “He knew how popular that early Christmas story was,” says Price, “and even as he matured as an author and his writing gained a darker tone, he was happy to continue to perform it. Unlike some of his early work, which he was very keen to distance himself from, there is no evidence of his feeling any distaste towards the Carol. I think he remained proud of it – and what it had given to his readers – all his life”.

Beautiful Books is at the Dickens Museum, London WC1 until April 19; dickensmuseum.com