Behind the Victorian-Era Obsession With Porcelain, There’s a Fraught History of Exploitation

The westward spread of the Chinese ceramics, known as "white gold," saw these objects become a fascination in upper-class households—and resulted in a damaged relationship between empires.

For most of the modern era, porcelain has been a common heirloom, a traditional wedding gift to a new couple, and a material that generally signified sophistication, upward class mobility, and maturity. During the 19th and 20th centuries, owning a special set of porcelain dishes meant something, a form of consumerist propaganda for the middle-class self.

In America, this is no longer true. Fussy dishes have fallen out of favor, and family meals are becoming less common as fewer people are willing (or able) to take the time to cook, sit, and eat. Now, we’re more likely to see porcelain in the bathroom than on the table. We’re more likely to see it on television, winking brightly at us from the mouths of our most chaotic reality stars and magnetic actors, their smiles fixed and brightened with layers of glue and clay. We still use porcelain, and we still consume it, but it’s no longer revered in the same way. The porcelain object I interact with most often is probably my toilet.

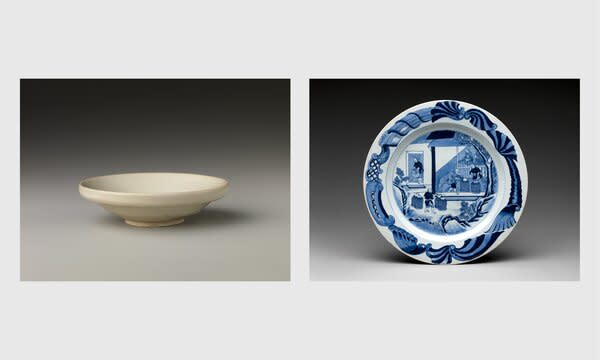

Not all fine china is porcelain, and not all porcelain is "true." There are several different definitions for the material. In China, porcelain is distinguished by its bell-like sound. "Resonant when struck," explains the Encyclopedia Britannica. European countries tend to define porcelain by its transparency—a fine china cup allows light to flow through its fine-grained, nonporous edge. According to some, the only true porcelain is that which includes kaolin, a type of clay mineral that we use in toothpaste, paint, cosmetics, organic farming, and ceramics. However, many people consider "bone china"—a British invention that uses cattle-bone ash mixed into the clay—to be of equal quality. There are chemical differences between these various porcelains, but for the average consumer they matter little.

The first pieces of porcelain were fired over two thousand years ago in the mountains of China. What made porcelain a distinct form of pottery was the introduction of kaolin into the mineral mixture. It took hundreds of years of experimenting to create the distinctive style of Chinese ceramics that would come to obsess Europeans, with its starkly white background and delicate cobalt-blue brush painting. While English speakers have often used the shorthand "china" to refer to our nice dishes, it was more commonly known as "porcelain," a name that originated from a comment made by the famous Italian trader Marco Polo. He noted that the dishware was as smooth, light, and pale as a cowrie shell, and so he called it by the shell’s Italian name—porcellana. This is also similar to a slang term for female genitalia, and according to some sources, it derived from the word for a sow’s belly—or maybe a young pig.

But long before porcelain made its way to Italy, it arrived in the Middle East. In 851, one merchant wrote of "a fine clay" from China that was used to make drinking vessels so fine that "one can see the liquid contained in them." While people in this region weren’t using porcelain to make their pots—they didn’t have the fuel to fire such hot kilns, for one, and they didn’t have access to kaolin, for another—they were still able to make finely decorated earthenware in traditionally revered colors, including cobalt blue. Some historians have speculated that the blue-and-white color scheme that would come to define porcelain in the European imagination originated in the Islamic world and was a result of many years of trading back and forth between cultures. Artistic practices don’t often stay within the borders of a nation-state, no matter how hard the powerful try. Inspiration moves across cultures, countries, and times, muddying the waters in a most beautiful way and obliterating the myths told about superiority and tribalism.

While there are similarities in the westward spread of porcelain and the movement of silk, it wasn’t quite as easy for other cultures to seize the secrets of clay as it was for them to plant mulberry groves. During the Yuan dynasty, merchants carried porcelain vessels, plates, and figurines along the Silk Road to trading cities in southern Spain and Italy. Medieval Europeans were immediately obsessed with these light, smooth, intricately painted pieces. They knew how to make pottery, but they couldn’t make anything like that. Chinese-imported ceramics took on magical qualities in the European imagination. Known as "white gold," porcelain objects remained prohibitively expensive for most households until the eighteenth century. They were a highly desirable but not particularly accessible object of fascination for the upper class.

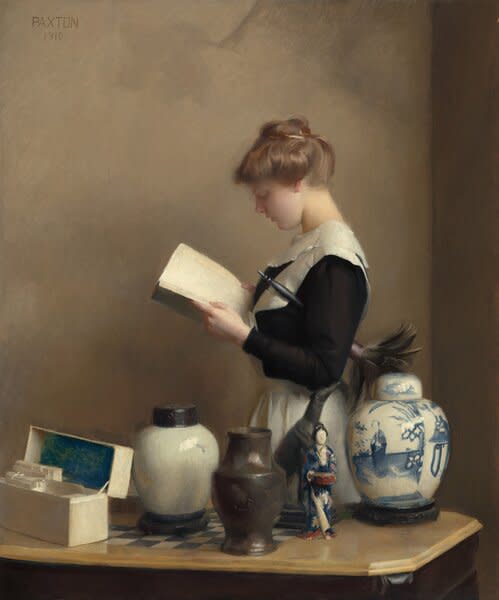

As more workshops began to pop up across the European continent, a number of different styles began to compete for marketplace supremacy. The most fashionable pieces came from France, where Madame de Pompadour, mistress to King Louis XV, used her considerable wealth and whimsical tastes to influence the artistic development at Vincennes and later Sèvres. The lady favored rose hues, and Pompadour pink became a favorite color for nobles shopping for gilded tureens or fanciful vases. Porcelain was so popular that dinner itself transformed during this time period. There were suddenly all these marvelous products that could be used to transform the dinner table into a miniature landscape, complete with elephant-shaped pitchers, boat-shaped tureens, and asparagus- shaped plates made specifically for serving buttered spring vegetables. The idea that a dining table could be representative of the hosts’ personalities and values began to spread beyond European nobility and into the houses of American merchants. A new era of eating had begun, one that was prettier and more public than ever before.

During the nineteenth century, the shift toward more stylized living spaces became widespread throughout the Western world as the middle class began to gain economic power and women were, for the first time, encouraged to stay inside instead of working in the fields or factories. This created an entire class of person—the housewife—whose raison d’être was caretaking, nourishing, and beautifying. During the Victorian era, there was a massive boom of consumer goods, and it became the job of the matriarch to buy them. While women were still unable to participate in many areas of society, they were encouraged to shop, attend dinners, and host parties. This is also when the lifestyle publication took off. For the first time, there were multiple magazines dedicated to women’s interests, including Godey’s Lady’s Book, which held up Queen Victoria as the very model of femininity and elegance. The British monarch had everything—diamond tiaras, silk lace gowns, a storybook romance, a line of porcelain named after her, and a drug habit.

During the day, Victoria purportedly chewed gum containing cocaine to give her a bit of bounce, and she often sipped laudanum—a beverage containing a tincture of opium. Maybe this is why she didn’t think it was a terribly big deal to begin introducing new users to the drug. She drank it, so how bad could it be? Or maybe she just didn’t care what happened to people in other parts of the world. Either way, it was under Victoria’s leadership that the British East India Company started a drug epidemic in China, smuggling in tens of thousands of chests per year.

They did it to correct the long-standing trade imbalance between the two empires. China had many desirable products that appealed to Victorian-era consumers. Tea drinking had become a ritualized event, one that came with an incredible number of accessories, from decorative teapots to mahogany tea caddies to silver tea urns. Tea came from China, as did the most beautiful porcelain (and the softest silk, the nicest paper, and such refined lacquer boxes). Unfortunately for the British, their own products weren’t nearly so popular in China. Perhaps if the populace just happened to get addicted to a substance produced in British-controlled India, well, maybe that could all change. Maybe they could get cheaper tea for their tea parties, cheaper porcelain for their tables, cheaper silk for their dresses.

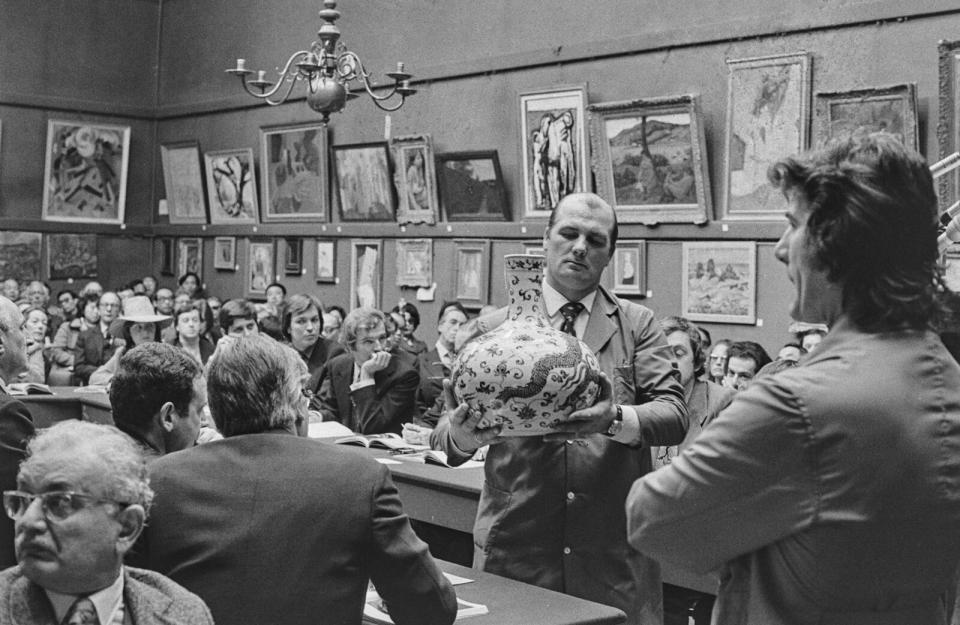

Opium, porcelain, tea, silk, silver. "It’s all interconnected," says Karina Corrigan of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. The museum has one of the richest collections of Chinese export art in the world, including large porcelain urns, small porcelain crabs, and silver- caged porcelain goblets. These pieces attest to the continued popularity of Chinese ceramics on the American dinner table, as well as the tangled, damaged relationship between empires. While other museums have struggled with the question of whether they should return looted treasures to their home countries, the Peabody Essex has a slightly different problem. When I’m gazing past the glass case and at the shelves full of decorative porcelain plates, figurines, and candelabras, I’m missing a huge part of the story behind these pieces. They weren’t just made for foreign tastes, thus turning them into fascinating hybrids of aesthetics and projected desires, they were also part of a larger system of exploitation.

See the full story on Dwell.com: Behind the Victorian-Era Obsession With Porcelain, There’s a Fraught History of Exploitation

Related stories: