This biathlete learned to speak Korean while training for the Olympics: It's 'like watching TV!'

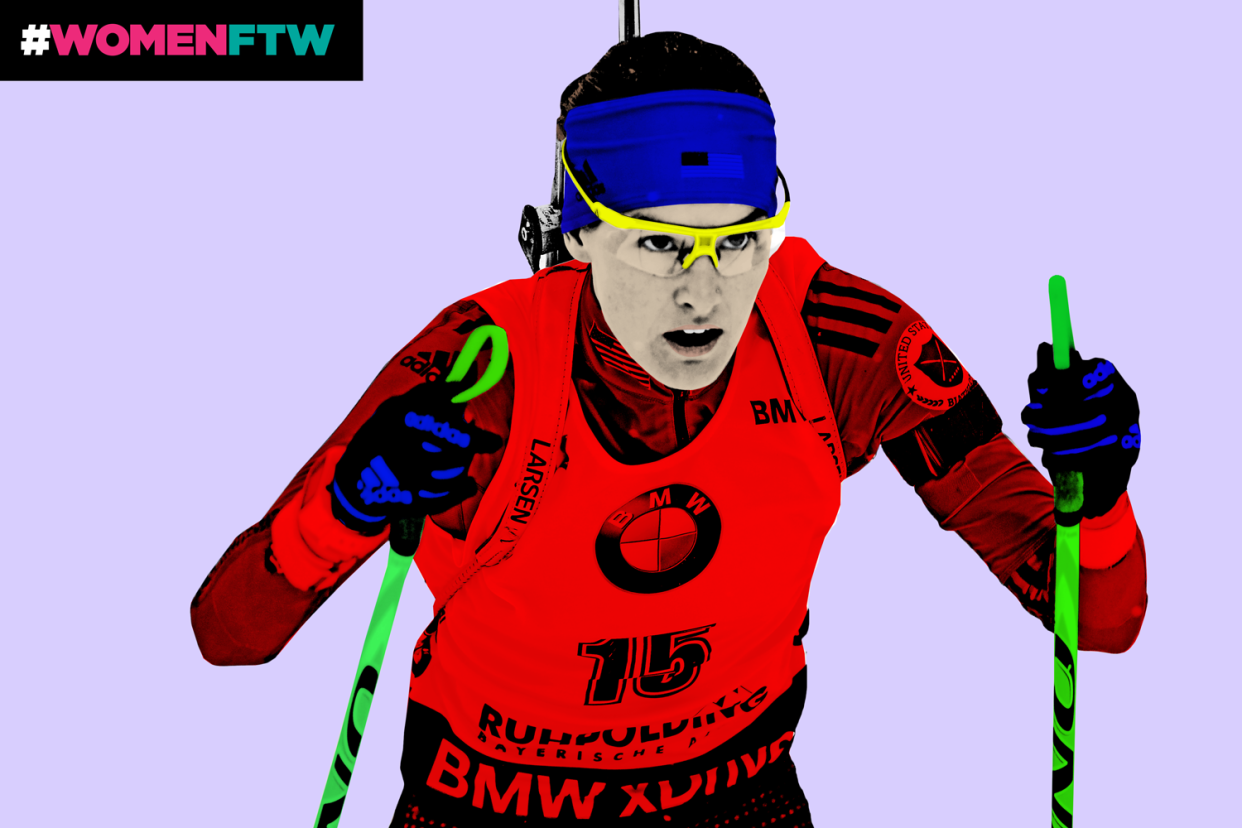

Clare Egan, a Team USA biathlete competing in her first Olympics, is not only a pro when it comes to cross-country skiing and rifle shooting — the elements of biathlon — but also at learning new languages. She speaks five already, and is quickly on her way to becoming proficient in her sixth: Korean.

“Learning another language is one of the greatest signs of respect,” the biathlete wrote in her personal blog recently, “and at a time when the U.S. is perhaps not viewed in the kindest light by our global neighbors, I hope my small voice can make a big impression.”

A post shared by Clare Egan (@clareeganbiathlete) on Feb 11, 2018 at 8:26pm PST

But her effort is not solely motivated by ambassadorship. “I’ve always been really intrigued by languages, and the connections that learning a language allows you to make with other people,” Egan, 30, tells Yahoo Lifestyle. “I guess I also like experiencing different cultures, so those things go together. I’m always trying to learn a language on the side. I feel like it’s one of these things where, if I can spend a couple minutes learning a language every day, I can probably speak 15 languages by the end of my life.”

Plus, says Egan, who majored in linguistics at Wellesley College, mastering a new language is also relaxing and fun: “For me, doing my Korean workbook is like watching TV. It’s downtime.”

A post shared by Clare Egan (@clareeganbiathlete) on Feb 4, 2018 at 11:33pm PST

Finding ways to unwind is vital for Egan, considering her grueling year-round training schedule: perfecting her skills twice daily, six days a week; doing intensive training camps; and spending five months on the road, competing, throughout the winter.

“Taking care of myself and making sure that I’m emotionally healthy, as well as physically healthy, is critical to doing well,” the Maine native shares, explaining that being an athlete is her full-time job, thanks to her annual $14,000 U.S. Biathlon Association stipend (“pretty good for a U.S. athlete…”), funded through private sponsors and the U.S. Olympics Committee. “I think it’s really important to do things every day that enrich your life and make you feel happy” and she tries to “do some non-biathlon things at least once every day.”

Egan, who has an athletic background as a runner and cross-country skier, discovered her love of biathlon a bit late in life, when a U.S. development coach offered to teach her how to shoot during a period of intense cross-country competition.

“I took coach up on the offer. I was really excited to learn a new skill that was totally different from anything I knew,” she recalls, explaining that her only experience with shooting at that point was at summer camp as a kid, when she’d had target practice. But she took to it right away.

“I liked the challenge of trying to be really still and really calm and really focused and precise, especially in combination with cross-country skiing, which is the opposite,” Egan says, explaining the difficulties of biathlon. “There’s the physical shaking, which is a challenge, and the breathing and the heart rate… But there’s also major mental challenges that comes with shooting, which is more like sinking your final putt in a golf tournament or hitting a game-winning free throw in basketball — something where you have the skills, you’ve done it a thousand times, but you have to execute it perfectly under pressure. And that’s what every shot in biathlon is like. So that’s why it’s an exciting sport to watch.”

Another challenge of the race, she adds, is the “volatility” of results, due to the combined skills at play, meaning that one day you could find yourself on the winners’ podium and the next day you could be way at the back of the pack. “That’s something that I wasn’t used to as an elite athlete in cross country skiing, and I think most elite athletes are at the top of their game and don’t often see themselves on the very bottom,” she says. “So that volatility is maybe the biggest struggle, and that’s a psychological struggle, not a physical one.”

Also adding to Egan’s Olympian battles: being a woman in a largely men’s world. “Almost all the staffers are men — so all male coaches, all male ski technicians. We have one woman doctor who is matched up with our team, which is cool, but it’s usually just all men and us,” she explains, noting that she is often the only woman in the room, and always “very outspoken” against any perceived sexism. “And I don’t think my team is particularly bad or misogynist, but it’s just our culture,” she says. “We have to stick together as a women’s team and stand up for each other.”

If Egan wins a medal on Thursday, she says, she’ll be standing up for one very special woman: her grandmother, 89, who lives in Maine. “She also went to Wellesley College, a women’s college, and I feel like she was a really strong and brilliant woman, though I don’t even think she had opportunity to do sports,” Egan said. “I want to dedicate my performance to her, whether or not I win a medal.”

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Meet Maame Biney, the first black woman to compete as a U.S. Olympic speed skater

Mirai Nagasu just landed a triple axel at the Olympics. Here’s how she did it.

What 11 Olympians do in the morning to start their days off right

What 11 Olympians packed to make PyeongChang feel a little more like home

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.