This Bottle Was Bourbon’s Greatest Mystery—and Worth a Fortune. Then They Drank It

Kevin Minnick immediately noticed the weird packaging: an old-fashioned wine bottle with deep punting, that indentation on the bottom of bottles; a cork covered in wax that had dripped flush against the neck; and—strangely—a Cuban tax strip pulled over the lip.

If you know anything about bourbon, one of its most prevailing regulations, aside from being made predominantly from corn and aged in new charred oak barrels, is that it must be distilled in the U.S. Yet this bottle claimed it came from Berman Liquor Co. Inc. in "Habana-Cuba." Even without opening it, Minnick could see the liquid was ridiculously dark, much darker than the amber color a bourbon should be.

The label claimed the whiskey was 'Bottled-in-Bond,' an alcohol-by-volume (ABV) classification created by the U.S. Congress in 1897, which meant the liquid must have been aged in a federally bonded warehouse under U.S. government supervision for at least four years, then bottled at 100 proof. Meanwhile, this bottle was only 90 proof.

In the vintage spirits game, you encounter plenty of strange anomalies, but it was hard to rectify all this conflicting, seemingly impossible information. Something so unique might fetch a hefty price in the rare spirits market. But unlike more cautious, economically minded bourbon collectors, Minnick knew instantly that he wanted to taste it.

"I was like, fuck it, man," says Minnick. "Here’s an odd bottle nobody’s really seen."

Minnick, a 45-year-old chef and restaurant owner, is known as a 'dusty hunter,' someone who seeks out vintage spirits. Dusty hunting arose in earnest in the aughts, with collectors scouring out-of-the-way liquor stores, estate sales, and even eBay in the hopes of scoring valuable bottles of booze from the past. As the 2020s arrived, it became harder and harder to make great scores, as most places were picked over. The most clever dusty hunters, thus, had to employ new tactics.

Minnick is one of the best. He has an incredible knack for finding things no one else even knew existed. His restaurant, The Maine Course in Quincy, IL, is famous for having one of the largest whiskey collections in the state. One of the keys to his continued success is his relationships with numerous 'pickers,' antique hunters who travel state to state sifting through junk to find gems. One of his picker friends has an interest in vintage signage, but not dusty alcohol—so he passes those finds on to Minnick. In Chicago, this picker found a small lot of booze containing two bottles of Horse Shoe Cuban bourbon. Vintage spirits only maintain their value if full and sealed. These bottles were both, marking a special haul.

Because of their high ABV, spirits are always safe to drink. And unlike wine, they don’t age in the bottle, so vintage spirits taste exactly the same as the day they're sealed. The two bottles of Horse Shoe Cuban bourbons were essentially liquid time capsules. But to what era?

Kevin Minnick

Minnick lugged a bottle of his latest find to the Grains & Grits Festival in Townsend, TN, a whiskey and Southern grub event he attends annually. Cuban chef Mike Behmoiras and his father identified the bottle as pre-embargo, which meant it hailed from 1961 or earlier. Once Fidel Castro seized power of Cuba in 1959, he nationalized the country’s rum distilleries. The Bacardí family and their company's top executives immediately fled to Puerto Rico, where they continue to produce the brand today. Meanwhile, Castro reportedly sent spies to Scotland to learn how Cuba could start making its own whiskey. But Horse Shoe’s confounding label reads bourbon, not Scotch, meaning it must have U.S. connections.

Exasperating Prohibition laws could be to blame for the unconventional label; numerous distilleries pulled similar shenanigans in other countries. Perhaps most famously, Mary Dowling, heir to the Dowling Bros. Distillery, dismantled her operations piece-by-piece and moved to Juarez, Mexico in the early 1920s. She hired Joseph L. Beam, one of the first investors in Heaven Hill Distillery, to make bourbon. In fact, Dowling’s Mexican distillery continued to make, according to ads, "Kentucky-type bourbon" until 1964, when the U.S. Congress declared bourbon a "distinctive product of the United States." After that point, no other countries could label their whiskey as bourbon.

Minnick took the second bottle of Horse Shoe to Kentucky, where several vintage whiskey bars and retailers have sprung up since 2017, when Governor Matt Bevin signed HB100 which allowed for the legal buying and selling of vintage spirits. Minnick took a seat at Neat Bourbon Bar + Bottle Shop, opened in Louisville’s hip NuLu neighborhood in 2022, and propped the bottle on the bar.

"Let’s open this and drink it," he told Neat co-owner Owen Powell.

"I looked at it, and I knew it was going to be special," Powell says.

As they sipped, the two vintage whiskey enthusiasts reckoned how the bottle came to be. Cincinnati-based Mill Creek Distilling Company, once offered a Horseshoe (one word) whiskey. Had a few bourbon barrels been smuggled out of Mill Creek—one of the "largest distilling companies in the country" as of 1885, according to Demorest's Monthly Magazine—during Prohibition? Had these barrels made the secret trek over the border to Canada—which also bottled its own 'bourbon' during this time, via brands like Gooderham and Worts—before being shipped down to Cuba, where it was bottled?

In 1937, Morris Roisner, part of a known organized bootlegging syndicate, was charged with tax evasion and put on trial in a St. Paul, MN, courthouse for illicitly sending $41,500 to Cuba during Prohibition. The recipient down there? Mill Creek Distilling Company in Havana.

Another lead? With rising anti-Semitism in both Europe and America, many Jewish people fled to Cuba after World War I. Some entered the cigar industry. Others started booze companies, like Philadelphia whiskey man Irving Haim, sometimes known as Haimovitz, who first worked as general manager of Maryland’s Sherwood Distillery Co.

According to Mark Haller’s Philadelphia Bootlegging and The Report of the Special August Grand Jury, Haim and his brother Charles moved to Havana in 1929 and set up Mill Creek Distillery, working with Minnesota bootlegger Leon Gleckman to get their spirits illicitly imported back to America.

Courtesy Image

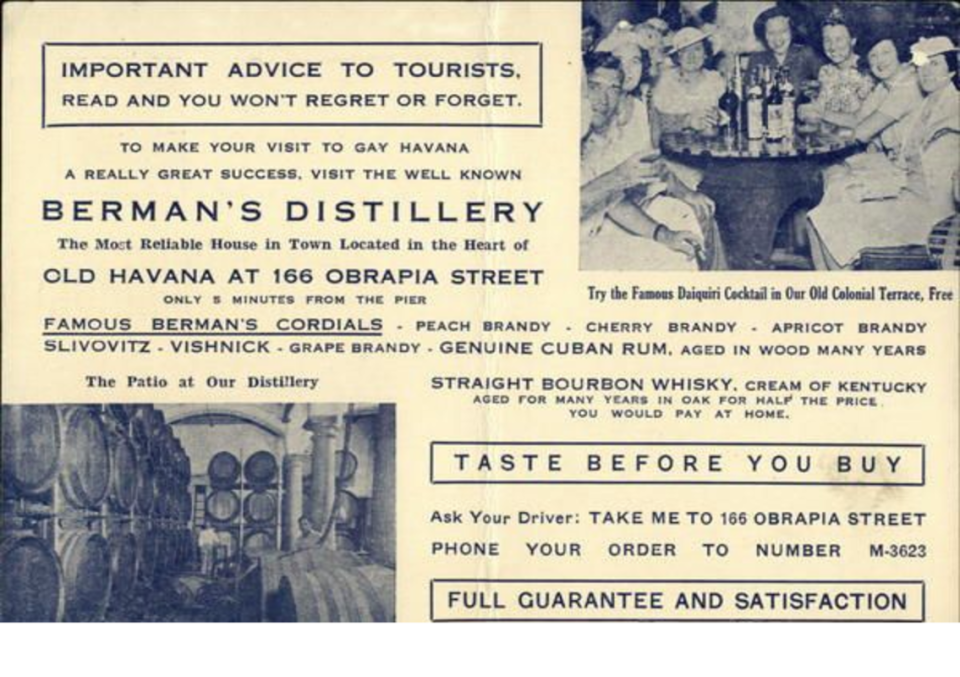

But Mill Creek Distillery isn’t written anywhere on the bottle. Instead, in black letters across the bottom, the label reads Berman Liquor Co. Inc. Dan Gifford, an independent historian in Louisville, believes Berman Liquor Co. was a retail and drinking stop for out-of-towners rather than exclusively a wholesale business or distillery itself. He found an old postcard advertising Berman, then located on Obrapia Street "in the heart of Old Havana … only 5 minutes from the pier," where ferries would drop off Americans arriving from nearby Key West.

"I could argue that the Berman Liquor Co. name on the [Horse Shoe] label was that of the retailer, which was a common practice, thus meaning it could have still come from the Mill Creek Distillery in Havana," Gifford says.

Berman, almost certainly another Jewish émigré, sold 'Famous Berman’s Cordials' like peach, cherry, and apricot brandy—along with slivovitz (plum brandy), vishnick (cherry liqueur), and Old Tranquility Brand rum—in handsome gold-necked bottles, as well as, yes, straight bourbon whiskey "aged for many years in oak for half the price you would pay at home," according to the postcard.

Courtesy Image

So, was Horse Shoe distilled in Kentucky, Cincinnati, or Cuba? All we know is that it was almost certainly bottled in Havana, then some of it made its way back to the States. In 1931 in Shreveport, LA, cops caught a man with 12 pints of Horse Shoe Bourbon in a hermetically sealed tin, apparently shipped to him from some great distance. In 1933, the Key West Citizen detailed U.S. customs officials stopping a boat from Cuba loaded with "good stuff," like twelve quarts of Hennessy, twelve quarts of Ron Can?a, twenty-four quarts of 1873 Bacardi?, five-gallon demijohns of gin, twenty-four bottles of Crystal beer, and, of course, fifty-one pints of Mill Creek whiskey.

Powell, who describes Horse Shoe as "phenomenal," speculates that the whiskey owes its flavor to those other liquids. Horse Shoe is viscous, with just a kiss of Cuban rum on the aroma and palate, making it a hair sweeter than expected from American oak. "Because it was bottled at a rum distillery, maybe some rum was still present in the bottling machine and got imparted into the bourbon," he says.

Minnick left him with about four ounces of Horse Shoe, and Powell immediately called bourbon industry friends like Heaven Hill’s Andy Shapira and Bernie Lubbers. Everybody who tried a sip was equally blown away. They agreed that it was one of the best bourbons they’d ever tasted.

Powell, who knows as well as anyone in the industry what vintage booze is still out there, believes Minnick’s two bottles might've been the only two left in America. And now, perhaps, there are none.

"It’s definitely my unicorn of all unicorns," says Powell, who speculates what Minnick generously popped might have been $100,000 worth of whiskey.

When I passed that info along to Minnick, he was silent for a second before responding. "Well, that’s interesting. I think that’s kind of a crazy story. Is it far-fetched? Maybe. Is it realistic? You never know what’s going to happen when it goes to auction."

Powell claims that if he knew then what he knows now, he would have demanded Minnick never open the whiskey, and instead send it to a local museum. "But I’m also glad that I drank it with him," Powell says.

Such is the struggle of any vintage booze enthusiast: diminish its value, or know what it tastes like?

Ever since he sipped it, though, Powell can’t stop thinking about the mysterious Cuban bourbon. He’s even considered hiring a translator and taking an expedition to Havana. Surely there are more bottles in someone’s closet, right? Maybe there are some dusty Horse Shoes hiding in the back of a store or warehouse or Castro’s old offices? There has to be. He knows there has to be.

In Aaron Goldfarb’s latest book, Dusty Booze: In Search of Vintage Spirits, he writes about a coterie of eccentric collectors searching the world for old bottles of whiskey, rum, and other libations from the past. He details pre-Prohibition ryes uncovered found in old Pennsylvania farmhouses and World War II-era bottles of rum located in shuttered San Francisco restaurants. He follows one man, Kevin Langdon Ackerman, hot on the tail of a collection that was supposedly sealed shut in Howard Hughes’ Los Angeles office after the entrepreneur’s 1976 death.

Solve the daily Crossword