The Brutal Fight to Include Women in Obamacare

Get ready, women, we are going to war!” Barbara Mikulski, a senator from Maryland and the longest serving woman in Congress, shouted into the microphone. Then she pulled out her bright red lipstick and smeared it on.

These were the early days of the fight for health care reform in 2009, and I’d accompanied Barbara to a press conference in the Capitol Visitor Center to announce Planned Parenthood’s support for Obamacare. Back then, the uninsured rate in America was at its highest point in a generation. At Planned Parenthood we saw every day how the lack of health insurance affected our patients. This was an opportunity to take a big leap forward.

The passing of Obamacare was long and arduous, and most people remember the fights over drug pricing or cracking down on insurance premiums. But neither of those were the most controversial pieces of the Affordable Care Act. Instead, nearly every knock-down, drag-out fight had to do with women’s health.

In one infamous hearing, Senator Jon Kyl from Arizona objected to covering maternity care, huffing, “I’ve never needed it.” Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan shot back, “I think your mother probably did.”

After many similar arguments had been waged and won, there was one last topic to resolve: the issue of abortion. A proposal, known as the Stupak Amendment, had been introduced at the last minute-with support from the US Conference of Catholic Bishops-that would prevent insurance plans from covering abortion services under the new health care law. The amendment went against everything we stood for at Planned Parenthood.

For help, I turned to Laurie Rubiner. Laurie had come on to run our government relations office in Washington, and she was smart and savvy. She had worked on health care policy on both sides of the aisle, including for then Senator Hillary Clinton. She'd spent years trying to convince Washington to stop talking about women’s health as merely a “social” issue, and start talking about it as a fundamental health care issue that affected half the country.

We tried to beat back the Stupak Amendment, but we just didn’t have the votes, and it was included in the bill passed by the US House of Representatives. If it passed the Senate and became law, it would be a done deal: we’d lose abortion coverage for women and never get it back. I was devastated. That was my lowest point in a long time.

Early the next morning I was in a hotel room when my cell phone rang. It was my old boss, Nancy Pelosi. “I know this is terrible, and I’m as mad as you are,” she said. “This was a last-minute attack and just know this: I am committed to getting the Stupak Amendment out of the final bill. I don’t know how, but that’s my word.” I thanked her, but I wasn’t hopeful. Having worked on the Hill, I knew that the likelihood of our changing the legislation was slim. And deep down, I knew that the White House would sign whatever bill came out of Congress. There was no way we could count on the president to veto the bill everyone in his administration had fought so hard for. I felt awful and, frankly, totally discouraged.

A few days later, Planned Parenthood leaders from across the country were scheduled to be in Washington for a meeting of the national board. Everyone was expecting an update from the front lines of the health care fight. Our organization had poured all of our energy into supporting Obamacare, and there was so much good in the bill, but I knew we could not support it the way it was. I just hoped the board would agree.

“This is it,” I told them, bracing for a tough conversation. “I am asking you to give me the authority to tell the White House and our congressional leaders that if the bill bans abortion coverage, as it does in its current version, we will lobby against final passage.” There was an uneasy silence. For months, our volunteers had rallied, made phone calls, and come to Washington to speak to their members of Congress-all in the interest of getting the Affordable Care Act passed. To see those efforts derailed would be awful. I could sense the board members thinking, All this work, for nothing?

The board went back and forth, recognizing that if Planned Parenthood opposed Obamacare over abortion, the entire bill might go down, hurting the millions of Americans in desperate need of affordable health care. I listened as they played out the same internal debate I’d been having for days.

In the middle of their deliberations Reverend Kelvin Sauls, a board member and preacher from California, cleared his throat. “The Bible says, ‘And I sought for a man among them, that should stand in the breach before me,’” he said. “The question we must answer is, Who will stand in the breach? Who will stand for the women we care for, at a moment of need for moral leadership? I believe this is one of those times when we are called to be in solidarity with women who may have no one else to stand in the breach.”

The room erupted with applause. Reverend Sauls had put into words what everyone was feeling. The board voted unanimously that Planned Parenthood would not support legislation that banned abortion coverage-even if that meant the defeat of the very bill we had worked so hard for.

It was my job to call the White House, knowing that they would be furious. It wasn’t the first time I’d had a big disagreement with the administration, and it wouldn’t be the last, but I had to remember what the president told me and other progressives after he was first elected: “It’s your job to make me do the right thing.” That sounded good as a slogan, but the reality was that no one liked being pressured by us. Our only real hope was Speaker Pelosi, and though I remembered her pledge to me weeks earlier, her opposing this bill, here at the final hour, seemed nearly impossible. I knew how important health care reform was to her, and to millions of Americans. Our position wasn’t popular enough to upend the entire bill. But I needed to tell her where Planned Parenthood stood.

Waiting at the Capitol for my appointment with Nancy, I knew I had to be crystal clear on our position, take it or leave it. “Thanks for coming in today,” Nancy began. “I know you understand we are within only a handful of votes to get this bill passed, and I’m not sure we can get it done. But we are working hard.” But before I could respond, she continued, “You know how much this bill means to me. I’ve worked for health care reform my entire career. But I want you to know: if there is an abortion ban in the Affordable Care Act, there won’t be an Affordable Care Act. I won’t pass it.” Her members were already hard at work whipping the votes, she said, and soon we would know whether the abortion ban had made it into the final bill-not to mention whether the bill could even pass.

We had Planned Parenthood supporters calling every member of Congress, either to buck them up or urge them to support only a bill that protected abortion rights. I was in Washington all week with the Planned Parenthood leadership, holed up in a conference room where we were getting reports from organizers out in the states.

Late Friday night the phone rang in my hotel room. It was Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro from Connecticut, a key lieutenant to Speaker Pelosi and one of my favorite members of Congress. We’d been in the trenches together many times, and Rosa had never shied away from a fight.

“Cecile, we did it! We backed them down. They threatened us over and over,” Rosa said. “And it won’t surprise you-several of the Democratic men were ready to sell us out. But Nancy didn’t blink. None of the women blinked. The Stupak abortion ban is out of the bill!” Joy and relief washed over me, along with an overwhelming feeling of gratitude for the women who had stood with us.

Two days later, the Affordable Care Act passed, and we made history. Without the women in the House and the Senate, it would have been a different story. For the first time, insurance companies could no longer charge women more than men for the same health care coverage-something that routinely happened before Obamacare. The many reasons women could be denied insurance coverage, from surviving sexual assault or domestic violence to having had a cesarean section, were no longer valid. And those pesky maternity benefits Senator Kyl objected to became part of the essential benefits all insurance companies have to cover. As Nancy likes to say, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, being a woman is no longer a preexisting condition in America.

Protecting coverage for abortion was a major victory, but certainly not our last battle in the fight for women’s health care. Part of the promise of Obamacare was that under the new law, preventive care would be covered for everyone with no out-of-pocket cost. We thought if we could make a case for contraception as preventive care, maybe women could actually have their birth control covered by insurance, like every other prescription medication in America. After all, Viagra was fully covered, so why not birth control? Planned Parenthood saw more than 2 million patients for birth control each year, but what we were talking about could be life-changing for tens of millions of women.

But we were fresh off a fight against laws that would let pharmacists refuse to fill a woman’s birth control prescription, and we weren’t about to take anything for granted. We needed both the medical and scientific community and the general public to stand with us like never before. Unsurprisingly, the public debate over birth control was Exhibit A in how little many of the men making decisions about health care legislation know about women’s health. It was a revelation to them that birth control could be anything other than a pack of pills or a condom. Men, including supporters of Planned Parenthood, had no idea how many women use birth control.

That shouldn’t have come as a surprise. A Fox newscaster once said that women didn’t need Planned Parenthood because they could go to Walgreens for their pap smears. That kerfuffle caused Walgreens to put out a statement telling women not to come to their stores expecting a pap smear. God bless Stephen Colbert, who was on it instantly, saying that women should go to Walgreens and look for the stirrups, right between the cat food and Swiffer refills.

One of our more successful lobbying visits at that time was with Senator Harry Reid, the Democratic majority leader from Nevada. We brought a group of women athletes from the University of Nevada–Las Vegas to see the senator, who had been a competitive boxer. They explained that they use birth control to regulate their menstrual cycle during the season, which improved their performance-a story he was eager to repeat the next time he saw me. “I met these incredible women athletes from UNLV,” he said. “Did you know they need birth control to compete?” “Well, yes, I did know that, Senator Reid, and thank you for meeting with them,” I answered. Meanwhile I was thinking, It was really worth it to bring these young women to Washington. They’re more effective than any paid lobbyist in town.

We had supporters in the White House, but we also had some very high-ranking opponents. The most organized force against us was, again, the Conference of Catholic Bishops, who understood that offering no-copay birth control for the first time would be a really big deal. While most of our organizing was public, theirs was primarily behind the scenes. We would show up at the White House, only to realize that the Bishops had been there before us, arguing that birth control was immoral-though the fact is that a huge majority of Catholic women use it. So we turned up the heat.

Members of the US Senate, led by Patty Murray and Richard Blumenthal, demanded to talk to the White House. Activists flooded the administration with letters in support of the birth control benefit. The mother of a Planned Parenthood staff member came up with the idea of sewing a human-size, wearable birth control pill pack. We named the costume “Pillamena,” and it made the rounds on college campuses.

Then, one afternoon in February 2012, my phone rang. The woman on the other end said, “Would you please hold for the president of the United States?”

“I can definitely do that,” I said. A minute later President Obama-who is notorious for being on time-came to the phone.

“Hey, Cecile, how’s it going?” he asked in a cheerful voice.

“Well, hello, Mr. President. It’s going just fine, thanks.”

“Cecile, I wanted to call you because I’m making three phone calls today: the Catholic Bishops, the Catholic Hospital Association, and you. Suffice it to say, I think yours is going to be the happiest phone call I’m going to make.” He paused. “I’m going to tell them the same thing I’m telling you: later today, I’m going to announce at the White House that, from here on out, birth control is going to be covered for all women under their insurance plans with no copay. I know you’ve worked hard for this, and I think it’s going to be a huge advance for women.”

I took a deep breath. “Well, Mr. President, thank you for calling me yourself, and for understanding what a difference this is going to make. We’re going to be busy making sure women know about this benefit and can get it.”

At our office, we hugged, high-fived, and took it all in for a few minutes. Then we started strategizing about what we needed to do to make sure no-copay birth control was a rousing success.

As soon as the birth control benefit took effect, women started walking into pharmacies to refill their prescriptions, walking out with another month’s supply of birth control with no out-of-pocket cost. They’d go to check out at the doctor’s office after a well-woman exam, ask what they owed, and hear the receptionist say, “The total for your visit is zero dollars.” Women started sending Planned Parenthood thank-you notes written on the back of a Walgreens receipt, with the copay circled: $0.00.

In the first year alone, women saved $1.4 billion on birth control pills. Today we’re at a 30-year low for unintended pregnancy, a historic low in teen pregnancy, and the lowest abortion rate since Roe v. Wade. These facts are too often overlooked, even though this is one of the biggest public health success stories of the last century. It didn’t happen on its own-it happened in large part due to better and more affordable access to birth control.

But of course elections have consequences. Since President Obama left office, women’s health has come under fire by the Trump administration, which believes insurance companies shouldn’t have to cover birth control. While the Obama administration was full of people- including the president himself-who were aware of how many women rely on affordable contraceptives, the current administration is home to high-ranking officials who claim birth control doesn’t work and don’t think it should have to be covered by insurance.

And even though abortion was legalized by the Supreme Court more than four decades ago, extreme politicians have been chipping away at a woman’s right to make her own health decisions ever since. In fact we’ve seen more attempts in the past five years than ever before to make it harder to access safe and legal abortion. Making matters worse is the appointment of Justice Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, who was one of the first judges to rule on the side of the arts and crafts store Hobby Lobby in a case that allowed employers to deny women access to birth control based on their own personal beliefs. I often think of the signs I see at protests for reproductive rights, typically held by women of a certain age, reading, “My arms are tired from carrying this sign for 40 years.”

But while the fight to keep abortion safe and legal can feel like it’s two steps forward, one step back, there is one area where we’ve made progress no one can take away. It’s hard to think of a medical procedure in this country that carries the stigma and judgment abortion does. Too often women’s experiences are seen through the lens of cultural and political battles instead of lived experiences. A woman who says she’s relieved after having an abortion is often criticized-though, based on thousands of post-abortion interviews, this is overwhelmingly how patients feel. If she says she feels regret, anti-abortion activists may use her words to push for laws that restrict abortion access or treat women as though we are incapable of making our own decisions.

Four years ago I started speaking more publicly about my own abortion. Before becoming president of Planned Parenthood, I hadn’t talked about it except to family and close friends. The truth is, it wasn’t an agonizing decision for me. It wasn’t tragic or dramatic-it was just my story.

Kirk and I were working more than full time and had three kids in school when I realized I was pregnant again. Like millions of other women, I was using birth control, but no method is foolproof. We were doing the best job we could raising our kids, and I couldn’t imagine we could do justice to a fourth. Having another child just was not an option for us. I already felt like I wasn’t doing enough for Lily, Hannah, and Daniel as it was. I was fortunate in that, at the time, accessing abortion in Texas was not the nightmare it now is for so many women. Being able to terminate a pregnancy early-it had hardly even begun-was a relief.

I realize women have many different feelings about abortion, and I respect that. But the thought that the government could force me or any other woman to carry out a pregnancy that was unplanned or unwanted was and is absolutely unconscionable. Many women have echoed how I feel; nothing makes you firmer in your belief in the right to abortion than being a mother yourself. I look forward to the day when men can empathize with an experience they will never have.

After my public declaration, women came up to me from Arizona to Maine to tell me that they had decided to share their stories, too. I’ve seen things I never expected: a major party’s presidential nominee talking openly about abortion in a national debate. The actor Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope having an abortion in prime time on the television show Scandal. (Thank you, Shonda Rhimes, for telling women’s stories.) Hundreds of women lawyers even submitted briefs to the Supreme Court in the Texas case telling their own abortion stories.

In 2016, I was at a conference celebrating 125 years of women students at Brown University, my alma mater. I was sitting in the audience, making last-minute edits to my speech, when a middle-aged woman took the stage to introduce me. Something in her voice made me sit up and pay attention.

Days before her graduation in 1968, she said, she traveled to Philadelphia for an illegal abortion. A few days later, barely able to stand, she got out of bed and welcomed her parents to campus. She managed to walk through the Van Wickle Gates to get her diploma, hiding how much pain she was in. Looking back, she said, she was lucky to be alive. She choked up as she said she would not be where she is today had she not been able to get an abortion. “We can’t ever go back,” she insisted. It was the first time she had ever told her story in public.

We’re still waging the fight for abortion access in America every day. But along the way we’re also transforming the culture, and that change can’t be reversed.

Taking on controversial issues is hard. Since my first weeks at Planned Parenthood, there have been people who have said, “Why don’t you just change the name, or split the organization in two, so people don’t associate you with abortion?” Sometimes these are well-intentioned people; they just want the controversy to go away. But what is important is that we quit apologizing for abortion and do everything we can to support people who need one.

Any time you’re trying to change the way things are or challenge the powers that be, it’s going to be controversial. Often the work that’s most worthwhile seems the most intractable and impossible. But just because someone else hasn’t figured it out yet doesn’t mean you can’t. After all, if it was easy, someone else would be doing it. And in the meantime, at least I’m enjoying fighting the good fight. The best and worst part about being a professional troublemaker is that the trouble never ends.

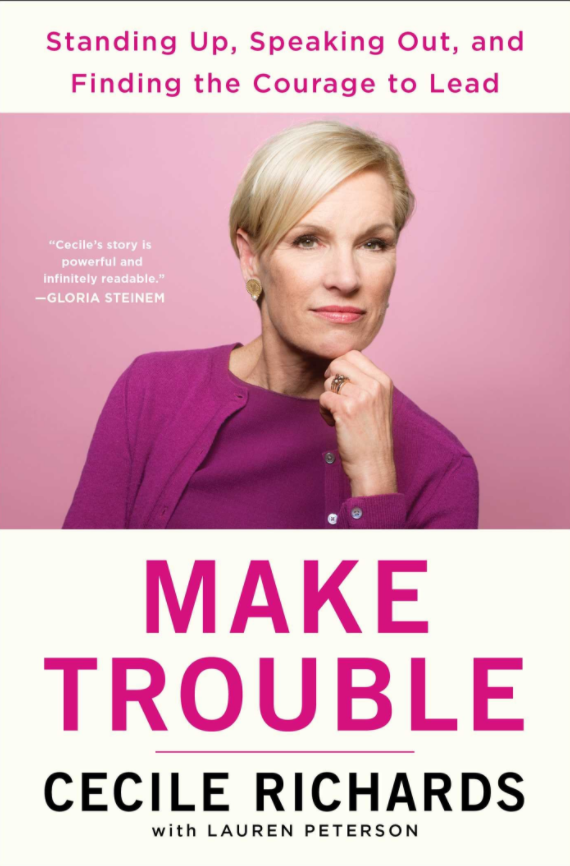

From Make Trouble by Cecile Richards. Copyright ? 2018 by Cecile Richards. Reprinted by permission of Touchstone, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Cecile Richards has been a lifelong activist for women’s rights and social justice, including more than a decade as president of Planned Parenthood Federation of America and Planned Parenthood Action Fund. Her new book, Make Trouble, is out April 3, 2018. Visit her website for a schedule of events.

You Might Also Like