Welcome to America's Greatest Cycling Memorabilia Archive, the Horton Collection

We will get to the scene in Eddy Merckx’s living room soon enough, the moment when the Cannibal hands over a mountain of jerseys. We will get to Jacques Anquetil’s bloody shorts and the whiskey with Bernard Hinault, and the Tour de France racer with the glass eyeball.

The journey, though, begins in a foyer. Moments ago I was walking up a steep little hill, smelling the ocean and watching wisps of fog sail eastward, and now I am staring down at Fausto Coppi’s water bottle, the weathered metal container—with a cork lid!—that the greatest swashbuckler in the history of bike racing tipped back in the Tour de France.

Next to it is an equally weathered hand pump, one that Il Campionissimo used to fix his own flats on training rides. I know this because Brett Horton tells me this. Looking casual in a gray polo shirt, Keen water shoes, and a black mask, Horton pantomimes a handshake as he greets me in the foyer of his San Francisco home. The items came to him via an Italian collector, he explains, who got them from the estate of Bruna, referencing Bruna Ciampolini, the sympathetically infamous wife of the champion rider.

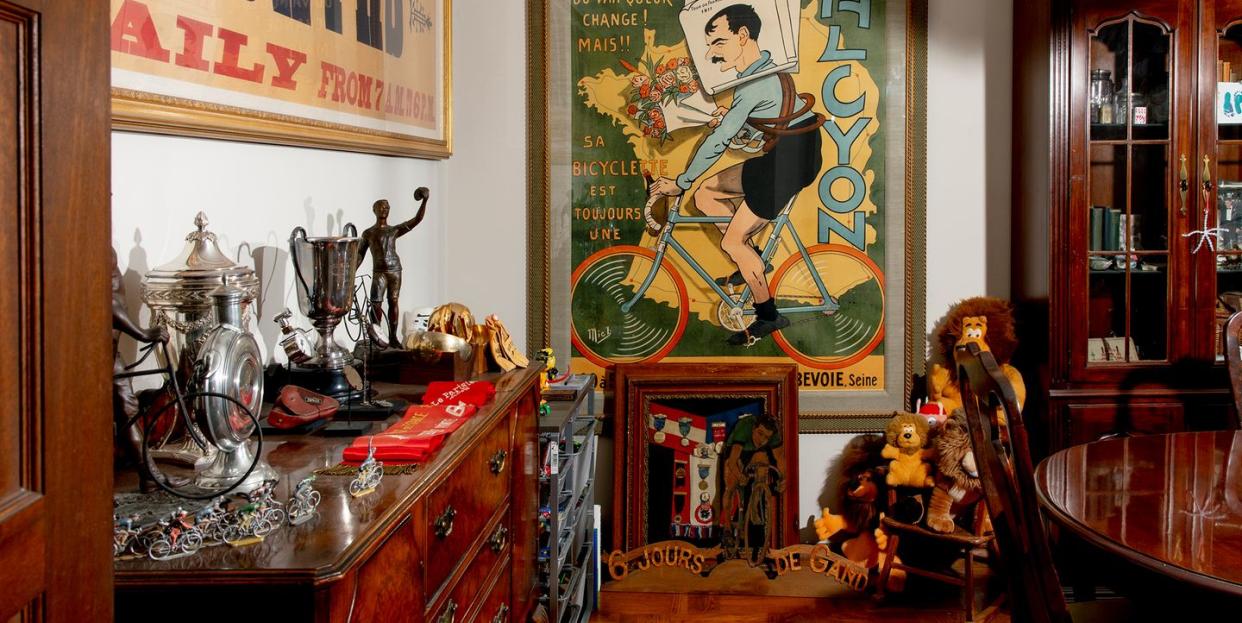

Soon thereafter, with his wife and business partner, Shelly, at his side wearing a matching black mask, we review the objects and art on and around the bureau in the entrance space. For an artsy bike racing geek like me, this is like a vestibule at the Hermitage. Right there is the original perpetual team trophy from the Tour de France. (A perpetual trophy is awarded annually and then passed on to the next year’s winner, like hockey’s Stanley Cup.) This heavy bronze chalice is mounted on a green marble base with serious deco vibes; it was first given to the top team on the Champs-élysées in 1930 and retired after the 1948 edition.

A few inches away sits the oldest known surviving award from the Tour: a small engraved bronze medal that was presented to Maurice Garin after Stage 1 at the scandal-plagued second edition of the world’s greatest bike race. (Eventually the fifth-place finisher would be named the overall champion.) Asked how that antiquity came into his possession, Brett laughs. “I got it by paying a heaping shitload of money for it,” he says without shame or swagger. “I acquired it at a public auction in Paris at a price that has never been equaled for a cycling medal.”

Thus begins an exhilarating marathon of a day touring the Horton home—which resembles a museum but with beds and a kitchen—and inspecting the hallowed Horton Collection. It is the finest assemblage of cycling memorabilia on U.S. soil and among the five or six greatest in the world. Before I stagger back out to the street nine hours later, I will have seen and touched hundreds of precious objects that were won or worn by Fausto and Eddy and Bernard and Jacques and Greg and many other extraordinary racers.

It is impossible to avoid being enveloped by the objects. But as the day progresses, the shock of examining the goods of the gods subsides enough for me to glimpse a deeper meaning. Collectively, this unparalleled array of medals, bikes, jerseys, photographs, posters, sashes, trophies, and artwork—along with other items best classified as beautifully random shit—has stories to tell about the fabric of the sport, the evolution of art and technology over the decades, of grit and passion and obsession, and the time-tested majesty of bicycles. These objects tell a story that informs nearly every pocket of modern cycling culture.

My visit comes at the end of June, when the world is still shell-shocked by a virus many thousands of times smaller than a grain of sand, a time when professional cycling is on an indefinite pause with no present and an uncertain future. Which is why this testament to cycling’s past, so gloriously crammed throughout the Horton household, feels particularly resonant.

“I’m now more interested in collecting stories and experiences than I am in collecting objects,” says Brett. This seems counterintuitive from someone who has spent decades—and millions—acquiring more than 15,000 historic objects and 600,000 archival photographs. I press him to clarify. “Select objects matter because they represent something important about the character of the riders,” he says, standing next to a medal earned when the Galibier was a dirt track. He says a friend once speculated that he was “collecting the souls of the riders.”

Brett and Shelly are sitting around the dining room table, discussing the nature of love. They’re talking about love in the broadest sense—a spirit that encompasses their marriage but also their business partnership and even their arguably obsessive infatuation for collecting. Eventually, with some coaxing, they will explain how this ardor led them to stalk Eddy Merckx in Belgium.

I have been in the corporeal company of Merckx and can testify that the Cannibal is present in the dining room. A glass-front display case contains about 30 items, including two sets of leather cycling gloves—one pair as dirty as a damp morning in Flanders—emblazoned with his name. There is a cozy tan-and-black Molteni winter cap that Merckx wore in the early ’70s. And on the table are jerseys—world championship jerseys and jerseys from Molteni and Faema and these amazing matching jerseys in Belgian national colors that Merckx and track deity Patrick Sercu wore in 1977 during six-day races. These are what are known as race-worn jerseys—the actual apparel worn during the most important events.

As Brett and Shelly pull out boxes of jerseys, they talk about how they met. It was at Brigham Young University, September 1986—and with a laugh, Shelly explains how they got to talking at sorority-fraternity mixer after Brett tried to pick up a friend of hers. “We hit it off immediately,” she says. They were engaged the following April and got married a year after that.

They moved to San Francisco in 1990 and into this house two years later. Though Brett’s career has gone well—he’s a financial consultant who advises clients on so-called alternative investments like hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital—they’ve never seriously considered moving. “We can see the ocean from the house, and we love our neighbors,” he says. “I like to spend my money on other things.”

Bikes played a role in both of their early years. Shelly grew up in a Los Angeles neighborhood not far from LAX, and she has happy memories of riding with friends down to Dockweiler Beach. In the Hortons’ living room is the gleaming cranberry-colored tricycle on which Shelly learned to ride. After their son, Trevor, now 15, was born, Brett had it restored with authentic period components and then repainted by legendary bike painter Joe Bell, who has painted bikes since the 1980s for Masi, Rivendell, Richard Sachs, and others. When it comes to bike stuff, Brett does not screw around

As a kid, Brett rode all over his San Jose neighborhood, and by the time he was 12 he observed that many of the other kids were riding elegant Peugeot 10-speeds while he was on a basic Ted Williams 10-speed from Sears. “My bike was the cheapest of the bunch and I was embarrassed,” he says. “So I decided I needed to win every race in the neighborhood.”

And so a bike racer was born. At 16, he was the youngest sitting in on hard club rides. Already on the beefy side, Brett learned early on that he could sprint better than he could climb. In high school, he hung a Campagnolo poster in his bedroom, of the ultimate Classics sprinter of the moment, Freddy Maertens. It showed Maertens powering to a narrow win in the 1981 World Championship, inches ahead of Giuseppe Saronni and Bernard Hinault.

Soon someone pointed Brett to the track, where he enjoyed his greatest successes. As a junior, he was Cat 1 on the track and Cat 2 on the road—good enough to win some NorCal state titles and qualify for track nationals. But he was self-aware enough to recognize that he lacked the talent to go significantly further. “I saw guys in their 20s who were driving their Pintos to win $100 primes in races,” he says. “Honestly, that didn’t have romance for me.”

Then, shortly before he stepped away from competitive racing, he had his first brush with collecting. At the track nationals in 1981, he was sponsored by Specialized founder Mike Sinyard, and he laughs remembering how he showed up with more skinsuits than he’d possibly need. He traded two of them for jerseys—one with a young Roy Knickman (who would later race the Tour de France) and the other with Dave Lettieri, who would go on to the Olympics and eight national titles. The Lettieri jersey—for a regional team sponsored by Getty Oil—now hangs at the foot of his home’s lower-level staircase.

Shelly, who calls herself “a saver who doesn’t really have the collector gene,” says Brett has always collected things. As a kid it was stamps and coins and baseball cards. When they first met, she recalls, it was comic strips and animation art. Later he was into San Francisco historical objects and dabbled in African art.

Cycling soon took over. It began, Brett says, when he decided to track down a pristine original example of that Campagnolo poster from his childhood bedroom. He talked to Jack Rennert, a well-known poster dealer in New York, and discovered that cycling posters had a rich 100-year history. He was a goner. Let’s just say that Brett Horton is not the sort of fellow to buy a few jerseys and posters and call it a day.

“I reached a point where I had to decide to either be a serious cycling collector or move on,” he says. “I came to the personal decision that I needed something from Merckx or Coppi to have a real collection. I wanted to play in the deep end of the pool.”

Thus began the stalking of Eddy. As Brett recalls, he cornered Merckx in 1994 at the Interbike trade show in Anaheim and told the Cannibal how much he’d love to buy a jersey or other memento from his racing career. Brett says Merckx told him to visit him in Belgium sometime to discuss it further.

It’s hard to say now whether the invitation was earnest or a blowoff, but Merckx almost certainly did not expect Brett and Shelly to show up at his door. That kind of unrelenting drive—to get on a plane or train and talk face-to-face with the source—has been a key influence in the growth of the Horton Collection.

At that meeting, Merckx asked his guests what exactly they wanted. Brett says he asked for a jersey from every team Merckx rode for, a yellow jersey and a pink jersey from the Tour and the Giro, and a rainbow jersey too. One can imagine Eddy listening to that, blinking and chuckling.

Brett remembers taking a deep breath and telling Eddy he’d pay whatever it took, whatever he wanted—even $1 million for a single jersey. There was a long moment of silence after that. Then Eddy excused himself.

After what only felt like an eternity, Eddy returned—with about 10 jerseys in his arms. He presented them to the Hortons one at a time, explaining the backstory of each. He offered to sell the batch for a lot less than $1 million per jersey. Still, it was clear to Brett that the offer of real money made a difference. “I’ve since made it a point to be generous when I buy directly from riders,” Brett says. “For one thing, they deserve it. And for another, they’ll probably tell other racers.”

These days, the Hortons and Merckx are something akin to friends—Brett says they’ll drink beers at the Ghent Six Day or grab a meal, and that Eddy answers his phone when Brett calls. They’re also undoubtedly business associates of sorts. The Horton Collection collaborates with the Cannibal and sells limited editions of signed lithographs. And Eddy has vouched for Brett with legends like Hinault, Sercu, and Roger De Vlaeminck, building relationships that have helped develop the Hortons’ collection and lithograph businesses—and frankly their life experiences.

[/image]

Sitting here 26 years later, Shelly and Brett can laugh about that early escapade. But back then they were stunned. “After we were done with Eddy, we drove back to our hotel in Ghent,” Brett recalls. “I stopped the car a few times along the highway, just to look in the trunk and make sure the jerseys really were there.”

Some of what was in that trunk is now sitting on the table, along with other Merckx jerseys acquired elsewhere—although Brett did trade one with Bradley Wiggins to get a Tom Simpson jersey. (“Those are rare,” he says.) Horton is loath to pick a favorite (“It’s like being asked to name your favorite child”), but then shrugs and says it’s undoubtedly the Molteni rainbow jersey Eddy wore when he won Liège-Bastogne-Liège in 1975.

Horton has found that the greats typically have more affection for their old jerseys, especially their regular team jerseys, than other collectibles. “I’ve talked to Merckx about this,” he says. “Eddy says the trophies seem more like souvenirs, and the bicycles just remind him of the suffering. But the jerseys remind him of the team and his happiest memories.”

Brett is in the living room standing next to the only custom children’s road bike that Eddy Merckx Bikes ever fabricated—it has pantographed Campagnolo components, including a stem cap that exclaims EDDY RODE CAMPY—explaining the duality of a legendary collection.

“Every collection is defined by the best 10 or 15 items,” he says. “You can see it at the Louvre, where people sprint past the Dutch masters to stand in front of the Mona Lisa. But at the same time, assuming there is quality, a collection is validated by quantity.” This is true, he says, whether you’re talking about fine art or coins or bottles of wine.

The Hortons have now spent a quarter century pursuing quality and quantity. Brett likes to talk about the three essential needs of any truly successful collector: time, money, and connections. We are standing within 15 feet of bike-racing equivalents of the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo, as well as hundreds of objects that are trivial by comparison but give the collection heft and texture.

One of the most precious items is a stopwatch first used as the official timepiece at the 1903 Tour; it remained in use until the First World War. Brett pursued this watch for years, he says, and finally acquired it, with the help of former Tour de France director Jean-Marie Leblanc, through the family of the Tour’s original timekeeper. “Things like that don’t appear by magic,” Brett says. “You have to hunt them down.”

Other headliners: The only known surviving original photographic print from the finish of the inaugural Tour de France in 1903. A shiny red sash that Coppi wore as race leader during the 1952 Tour. A World Championship trophy that belonged to Freddy Maertens. Yellow, green, and rainbow jerseys race-worn by Anquetil, Hinault, Sean Kelly, and, of course, Merckx. There is also this amazing engraved pewter drink set awarded to Hugo Koblet, who won the Tour and the Giro in the early ’50s, that the Swiss legend would pull out for after-dinner cocktails when esteemed company dropped by.

Throughout the day I also see many beautifully peculiar things that highlight the beautifully peculiar nature of riding bikes, things that don’t explain who won the biggest races but that contextualize the cultural relevance and idiosyncrasy of cycling. Some examples: a team-issued suitcase issued by Felice Gimondi’s Salvarani squad in 1966; intensely graphic original artwork by Japanese-born artist Munetsugu Satomi, used for posters and race programs to promote the 1933 Paris Six-Day; a stunning 100-year-old photo of participants in a French bike race restricted to men who weighed at least 100 kg; a strangely tiny mounted saddle—a salesman’s sample—roughly the size of a Matchbox car; a bike-racing themed slot machine featuring Paris’s Velodrome d’Hiver; a pair of shorts from Anquetil with a bloodstained chamois; a record album adorned with the faces of Coppi, Bobet, Koblet, and other champions; a six-course menu for VIP guests at the 1928 Paris Six-Day, capturing the flavor of pre-Depression decadence; sheet music that celebrates classic tunes for the track; a 1921 photograph of French racer Honoré Barthélémy alone on the Galibier.

If Barthélémy’s name draws a blank, consider the strange story of how he got flint in his eye during the 1920 Tour and finished eighth overall despite being blind in one eye. In 1921 he was fitted with a glass eye that often would pop out during races, but despite his ocular issues, the Frenchman still finished third overall when the race got to Paris.

“You can’t make this stuff up,” says Brett.

“A lot of our stories begin with someone dying,” says Shelly with a bright smile, looking up from her computer. We are on the home’s lower level now, in the office where she manages the Hortons’ e-commerce business.

The room is jammed with a reference library of books and periodicals, and flat file cabinets filled with fascinating ephemera—technical drawings by Daniel Rebour (perhaps the greatest illustrator of bicycles ever), the 1929 patent artwork for one of the first freewheels, and several massive sign-in boards from the Tour of California. There’s also a quirky helmet collection that includes a 7-Eleven aero model and lids worn by Greg LeMond, Jan Ullrich, and Erik Zabel.

Eventually Brett gives me a tour of the garage and lower level. The garage is densely organized and claustrophobic, a maze of filing cabinets and shelving units. Random bits of awesomeness—like a comprehensive collection of 7-Eleven team memorabilia, including Rebecca Twigg’s skinsuit and Bradley Wiggins’s trophy from his last professional victory at the 2016 Ghent Six-Day—hide in unlikely corners.

While the home’s main level is the private display space, this floor contains the nerve center of the Horton Collection’s online business. An area where most people would house a couple of cars and a playroom contains shipping and receiving, storage, the home office, and the photo agency.

Amid a collection that seems boundless, Horton’s approach to bike acquisition is restrained. He has decided to cap his collection at 24 bicycles, because that’s how many crates he can fit in his storage area. “Funny thing, this somewhat arbitrary limit has helped me immensely,” he says, explaining how a potential new race bike, if he really wanted it, would need to displace his 24th favorite bike.

Horton’s favorite bikes are the ones ridden by the racers he’s gotten to know—bikes with palmarès and stories and history he relates to firsthand. None seem more personal than the elegant, custom-made blue Colnago that Freddy Maertens threw over the finish line at the 1981 World Championships in Prague, just inches ahead of Saronni and Hinault. Imagine that: The kid who had a Campy poster of that finale now owns the bike, the jersey, and the trophy.

Near the bikes are rows of large file cabinets that hold what might be the world’s largest private collection of historic bike-racing photographs from the 1880s to the late 1970s. Who would think there would be an entire file folder of original photos of Louison Bobet from the 1950s? They are filed with precision, so if someone wants an image of a young Gino Bartali at the 1935 Giro or a portrait of one of Gimondi’s long-forgotten domestiques, it can be found quickly. Over time, because of the archive’s quality, the Horton Collection has evolved to become a busy photo agency, supplying historic photographs to media outlets and other clients. “We have photos of the stars and photos of the water carriers,” Brett says, pausing. “Folks only seem to ask for photos of the water carriers when someone dies.”

When asked who has the rights for 100-year-old bike-racing photos, Brett rolls his eyes. “It’s complicated,” he says. “Who has the negative? Who has the oldest known print? What copyright treaties exist? These are tough questions to answer sometimes.” After years of discussion and a fair amount of money spent on legal research, he met with officials from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, who ultimately conceded that he was free to license his old Tour photos. They “respectfully requested,” however, that he acknowledge the agency as the “moral rights holder to honor the cultural heritage of French cycling.”

Looking down the row of cabinets, I ask Brett how he knows how many photographs he owns. “We have approximately 600,000 photos and I’ll tell you how I know,” he replies. “We certainly didn’t count them—too much trouble. We weighed them.”

Shelly runs a successful e-commerce business that sells anything from a $4.95 postcard featuring a 1960s Italian pro to a $780 jersey signed by the Dutch legend Joop Zoetemelk. There are lithographs signed by the greats, original vintage posters and museum-quality poster reproductions, and old podium pennants. And there are far more expensive items not listed on the site that the Hortons will sell to interested collectors.

Both Brett and Shelly are committed to the Horton Collection’s digital presence, if for different priorities. For Shelly, it’s a much-appreciated revenue source and a way to share stories and bring order to the sprawling collection. Brett will often buy a big box of objects at an auction because he wants one or two items in the lot, and it falls to Shelly to manage the remainder. “He often picks something up with delight and asks, ‘Hey, I wonder where this came from,’” she says. “Like it fell from the sky.”

Brett—the primordial hunter and gatherer—appreciates the revenue and the history and Shelly’s quest for order, but he loves how the collection’s digital presence keeps the rich history of the sport, and the collection itself, alive in the public eye. That way, the next time a story begins with someone dying, it ends with something cool in his dining room.

If you talk with the Hortons about their collection, the narrative eventually pivots to either a methodically organized plane trip to a foreign country or a hastily organized plane trip to a foreign country. In 2005, when Brett heard that Danny Clark—arguably the second-greatest Six-Day track racer in history—would be willing to part with some jerseys and trophies, he didn’t hesitate to book a 15-hour flight to Brisbane, Australia. Another time, in Paris—where Brett happened to be buying an Anquetil yellow jersey—a gentleman in Zurich reached out. It’s one of those stories that begins with someone dying. The man was hoping to find a home for a trove of items that had originally belonged to Koblet. Within hours Brett was on a train to Zurich—and bought the entire collection the next day.

Over the years, these trips have taken on a deeper, more personal meaning for the Hortons. “We started to acquire jerseys, but it turned into such an interesting way to see the world,” says Shelly. For many years, the couple made eight or 10 trips a year to Europe. They’d fly for a weekend to catch a Spring Classic. Or spend a week at the Ghent Six Day. Or go wherever the road or track world championships were being held. Shelly’s favorites are the Belgian Six Days—“those are like going to a really great bar with a bike race attached,” she says, noting that Trevor was 12 weeks old when he went to his first Ghent; he took his first steps there a year later.

At some point along the way, the Hortons realized that they were a little less interested in collecting objects and way more interested in building lasting relationships. Living in San Francisco turned out to be fortuitous, as the city became an annual hub for the Tour of California. Shelly recalls memorable dinners with riders and entire teams. One year, after buying a set of high-end binoculars and doing quite a bit of internet research, they took Phil Liggett (an avid birder) out for a day of birding up at Bolinas Lagoon.

“I got into this to start collecting objects,” Brett says. He still actively pursues special items, but it’s the stories that interest him more.

When Brett set out to visit Bernard Hinault at his home in the Brittany region of France, it was ostensibly to have a new collection of lithographs signed by the Badger, who’d won 10 Grand Tours, a World Championship, and four Monuments. It turned into five days of sharing whiskey and rustic dinners and stories—about Hinault’s youth in Brittany, about his grandkids, about the hallmarks of a life well lived. As a parting gift, Hinualt gave Brett a few photos from his childhood and teenage years. “Those memories mean more to me than a race-worn jersey now,” says Brett. “I realize how lucky I am.”

Another such trip was to Ireland, where Shelly and Brett visited Sean Kelly in 2002. They’d spent some quality time together in 1998 when Kelly toured the States on a junket. The Hortons had set up the Classics specialist in the presidential suite at the historic Westin St. Francis in San Francisco, and even got hotel management to hang an Irish flag outside for a day. After an epic tour of the city and during a long evening of drinks, Brett told Kelly—who’d won seven Monuments and the points competition in the Tour de France four times—that he wanted to buy a race-worn jersey.

“I’ll give you a green jersey,” said Kelly, referring to the jersey given to the winner of the points competition of the Tour. “But you’ll have to come to Ireland to get it.”

They wound up staying in Kelly’s home in the Waterford area, and Kelly took them to the historic Waterford crystal factory and to a gritty local pub near his house. “We could tell he didn’t go out like that very often,” Brett says. “Every time we walked with him into a room, everyone would stop talking and swivel their head like it was an old E.F. Hutton commercial.”

Even now, Brett can get giddy talking about the doors opened by his collecting. Like the time he was seated with Merckx and Sercu at the Ghent velodrome. “I mean, let’s be honest, I’m just this dopey kid from San Jose,” he laughs. “And I’m drinking beer and laughing and watching a Six Day with the god of road cycling and his equivalent on the track.”

I am ready to leave—long past my hard stop to get home. But we’re back at the dining room table, talking about the meaning of this crazy enterprise. The home is a monument to the beauty of cycling, and also to obsession and passion.

I ask if there is an endgame; the short answer is no. Shelly says she thinks they’ll collect until they die. “I can’t imagine Brett not doing this, but it’s not like I just want to stick my kid with all this stuff.”

“I’m trying to get rid of more than I buy,” says Brett. “I realize that we don’t own the collection; the collection owns us. I think about Trevor and the market liquidity of this stuff. It’s not like owning shares of Intel.”

Still, the fire is still burning, and as much as Brett collects experiences, he also still collects objects. So I ask him to name the Holy Grail—the thing he wants more than any other thing.

“The Holy Grail is still out there,” he says. “More than anything, I want the skinsuit Eddy wore when he broke the hour record.” He is referring to Merckx’s legendary 1972 ride in Mexico City, when he covered 49.431 kilometers in 60 minutes—a record that stood for more than 40 years.

“Right now the answer is no,” says Brett. “Eddy’s not so financially motivated these days. It’s not like 25 years ago when he was running a small business.”

“Still, I try to ask him about it once a year,” he laughs. “He always says he’ll think about it. You never know.”

Shelly, meanwhile, is committed to the granular value of the history. She’s telling me about recent research she did to contextualize an old postcard they’re selling. It sounds like a lot of work for a $25 postcard.

The postcard shows a photograph from the 1910s of a Belgian racer named Georges Goffin posing on his bike behind a motorized Derny. Shelly tells me the rider from Liège liked to call himself Nemo—it’s not known why, she says, but perhaps it’s worth noting that Nemo means “no one” in Latin. Fittingly, Goffin entered the Tour de France three times and finished exactly zero times. He never even finished Stage 1. And yet, as the old postcard testifies, he just kept trying.

That is the history that joins us all. We ride a bike—sometimes trying to push our boundaries or chase victory, sometimes suffering or struggling, always part of something larger. Just as bike-racing culture is informed by the artful dominance of Eddy Merckx, it is also informed by the futile tenacity of Georges Goffin.

Shelly understands this dichotomy. “It’s a funny old postcard, I get that,” she said, her elbows on a table stacked with 100 years of yellow jerseys. “But it’s a funny old postcard that keeps the past alive.”

You Might Also Like