Cancel culture will fizzle out - as these lessons from history prove

What is cancel culture? Barack Obama compared it to “casting stones”. Donald Trump called it totalitarian. Both terms are drawn from the past; both imply that it’s nothing new, and it’s not. It’s a depressing retread of man’s worst instincts but – the good news – it’s not nearly as bad as the horrors that came before. We need some historical perspective.

Cancelling is when a group, usually online, tries to drive a controversial figure out of the public sphere – not just rebuke them but silence them for good. It seems to find its origins on Twitter in the mid-2010s. At that time, a number of powerful celebrities were being outed as sexual predators, and the idea of “cancelling” Bill Cosby or Michael Jackson mixed old-fashioned morality with 21st century consumerism. When you don’t like a publication, you cancel your subscription. When your hero does something that disgusts you, you cancel your fandom.

An early subject was the comedian Roseanne Barr who tweeted that Valerie Jarrett, a respected black politician, is what you’d get if “Muslim Brotherhood and Planet of the Apes had a baby”. Barr was cancelled, literally; she lost her TV show. Yet she’s never quite gone away and can regularly be found in front of a camera insisting she was misunderstood. A paradox of cancel culture is that its targets usually go down in a blaze of publicity.

As time went by, cancellation evolved from a reaction to events – celebrity does x, public responds with y – to a proactive policing of opinions and language, and this, say its critics, is having a chilling effect upon public life. Offence isn’t necessarily intended; it is inferred. Online detectives will trawl through your past to find a “crime” and expose it. Opinions that were considered mainstream a few years ago are now condemned as “problematic”.

Some examples: activists have tried to cancel J K Rowling for her views on transgenderism. Niel Golightly, a communications chief at Boeing, had to resign over an article he wrote 33 years ago saying women shouldn’t serve in the military. Roger Scruton, the philosopher (who has since died), was sacked from a government position after being misrepresented in the New Statesman. Actor Laurence Fox feared his career was over after he denied that Britain is racist. Anchor Alastair Stewart quit ITN after quoting a passage of Shakespeare that referred to an “ape” while in a Twitter spat with a person of colour.

Stewart never intended offence and even the man he was arguing with called it “regrettable” that he had to go. Yet the transition from controversy to cancellation can be incredibly fast, which tells us that employers regard social media as a genuine barometer of popular opinion. In the judgment of Helen Lewis, one of the sharpest observers of internet culture, shedding a cancelled employee is a comparatively cheap way for a company to protect its reputation and identify itself as progressive.

Because cancelling doesn’t just say something about the cancelled; it allows the canceller to affirm their own values and identity. Obama described it as an assertion of “purity… accelerated by social media” and common among the young. He was instantly dismissed as an out of touch old man. There is undoubtedly a generational quality to cancelling: while older progressives regard free speech as essential, younger activists worry it is being used as a cover for prejudice. Cancelling is not authoritarian, say the young: it’s a form of fighting back. Just as the powerful have always crushed the weak, so they are using what little power they have to cancel the bigots.

If shutting people down is a very old practice, so is putting the past on trial. In 897AD, Pope Stephen VI took revenge on his long-dead predecessor, Pope Formosus, by having his body disinterred and tried by a clerical synod; in the interests of fairness, the cadaver was even assigned a lawyer. Formosus was found guilty, the fingers he had used to bless were cut off and he was buried in a pauper’s grave. Stephen insisted the body then be dug up again and tossed in the Tiber.

There is a palpable need in politics not only to win but to discredit, to prove your opponent isn’t just wrong but a bad person. It wasn’t enough for the French revolutionaries to accuse Marie Antoinette of treason, they had to throw in the charge that she had sexually abused her own son. In 1950s America, Joseph McCarthy drew a line from treason to sexual difference, implying that communists were likely to be gay, and gay people, due to blackmail or general decadence, likely to be communists. Through smear and character assassination, he helped remove Leftists from civil service, education and Hollywood, while on the other side of the Cold War, the Soviets not only killed their opponents, but expunged names from the historical record and edited faces out of photographs.

This was damnatio memoriae, literally the damnation of memory, and for societies of the ancient world – when honour and good name were paramount – the damnatio was considered a fate worse than death. Statues, symbols of power and status, were fair game. After Demetrius of Phalerum was overthrown in 307BC, the 300-odd statues to him in Athens were melted down to be turned into chamber pots – a popular historical joke. It is said that Louis XVI commissioned a chamber pot with Benjamin Franklin’s face on it, so that the user could pee in his eye.

Contemporary cancelling has religious parallels, comparable to the early Christian war on pagan idols or the sacking of Catholic shrines during the Reformation. From 1692-1693, the devil apparently ran wild in Salem, Massachusetts: over 200 people were accused of being witches, 19 were hanged and one man pressed to death beneath rocks. Fanaticism is one explanation, another is that Salemites were settling old scores. Christianity is on the wane now and, for many Westerners, identity politics has taken its place – so, maybe what we’re seeing here is an attempt to establish new pieties enforced by a new inquisition, in which case, it’s helpful to remember that iconoclasm was never just about theology, that it also served a practical purpose.

Moral panic tends to break out during periods of stress and uncertainty. Take the story of Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar who rose to prominence in 15th-century Florence after accurately predicting a French invasion, and (less accurately) the end of the world. His preaching inspired a popular republic and a grand campaign against decadence. His followers, typically young, clothed themselves in white and went from door-to-door collecting tapestries, paintings, antiques and cosmetics – “vanities” that were piled up and torched on a giant bonfire. Much of the desolation was technically voluntary: just as we are invited to confess our privileges today, so the Florentines were encouraged to self-criticise and repent through immolation. It is rumoured that Sandro Botticelli, painter of The Birth of Venus, was so moved by Savonarola’s words that he threw some of his own creations on the fire.

Savonarola’s fanaticism spoke to the psychology of the moment: the destruction of names, memories and things, was a method of taking back control – of purifying the republic. But it ran its course. The friar fell out of favour with the mob, testing their credulity and patience, and was tried for heresy. He was simultaneously hanged and burned in 1498. His ashes – like Formosus’s – were scattered in a river to prevent his grave becoming a shrine.

Another forerunner to cancellation was China’s Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, when platoons of devoutly atheist Red Guards went to war on old ideas and the (mostly) old people who held them. In a widely-read column, American conservative Peggy Noonan has listed the similarities. The Red Guards were young, she notes; the victims were charged not only with thinking incorrectly but having bad habits and customs. “Dunce caps, sometimes wastebaskets, were placed on the victims’ heads, and placards stipulating their crimes hung from their necks.” Crowds were necessary – “it was important that the electric feeling that comes with the possibility of murder be present” – and in these so-called “struggle sessions”, a war was waged for the very soul of society, on the principle that one rotten apple could poison the whole barrel. “The spirit of the struggle session is all over Twitter,” observes Noonan. “The tormentors are not satisfied by an apology. They’re excited by it and prowl for more prey.”

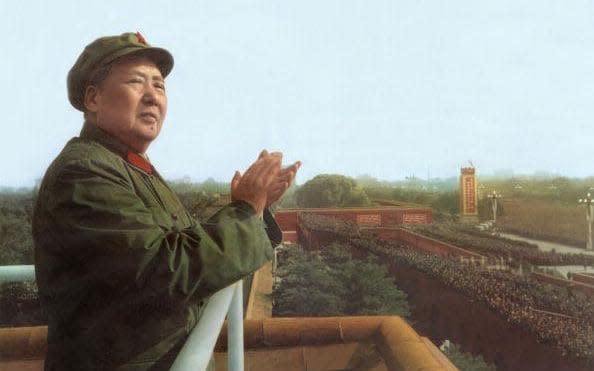

The Cultural Revolution might have been carried out by the young but it was launched by a very old man, Mao Tse-tung, and he did it because he had been sidelined by his colleagues in the Communist Party and was frightened of losing his influence. Mao encouraged chaos to regain authority. Likewise, it is no coincidence that cancellation accelerated around the time that Britain voted to leave the EU and America voted for Donald Trump. It’s easy to see cancel culture as an attempt by the Left to win a victory on social media, having been beaten at the ballot box.

The limitation of Noonan’s comparison with China, however, is its hyperbole. Millions of Chinese were murdered during the Cultural Revolution; Roseanne Barr losing a sitcom doesn’t compare. And are we really supposed to believe that conservatives wouldn’t cancel someone if they could? They almost invented the weaponising of old tweets. In 2017, a rabble-rouser called Mike Cernovich dug up one, ancient, sarcastic and uncontextualised tweet by radio host Sam Seder that got Seder terminated from MSNBC; a year later, Cernovich used some of director James Gunn’s most tasteless jokes, nearly a decade old, to get him canned from Disney. It was no coincidence that Seder and Gunn were critics of Trump, and in a rerun of McCarthyism, their words were used to insinuate that they were not only far-Left but sexually depraved. The benefit of the doubt be damned; the supposedly inalienable right to free speech, so beloved of the Right, flew out the window.

Here in the UK, after Priyamvada Gopal, an academic, recently said “white lives don’t matter”, conservatives demanded her sacking. When the ice cream firm Ben and Jerry’s stood up for refugees, conservatives called for a boycott. It is possible that the real moral panic isn’t about cancel culture itself – but a paranoid terror of fanatical young socialists that serves the Right’s agenda to cast anyone who disagrees with it as a threat to freedom.

There is something that does make this era unique, however: technology. Ideas drive history, but technology determines how that process plays out, and the internet has radically intensified an evergreen phenomenon.

Savonarola and Mao would have loved social media: it’s a tool for chaos and control, it lets a billion people talk freely, but it also generates mobs and empowers bullies, because when everyone’s thoughts are beamed directly on to a computer screen, the watchdogs can see what we’re thinking and do something about it. Social media has become part of our daily lives, yet the law has not caught up with it – Facebook and Twitter, ultimately, are not liable for what gets published on them – and neither has our cultural etiquette. Some people don’t seem to know when to keep their thoughts to themselves; others can’t tell the difference between a joke, a faux-pas and hate speech. It is easy for employers and the police to exercise a fixed policy of refusing to tolerate intolerance – one infraction and you’re finished – but it’s much harder to exercise the human quality we call “the benefit of the doubt”. The consensus on Twitter is often mistaken as a reflection of the values of the rest of the country; in fact, there is a growing gap between socially-sanctioned, politically correct opinion and what most of us actually think.

History shows that when this gap grows too large, and the public finally loses patience, the cancellation stops or even – as happened to Savonarola – is thrown into reverse. Revolutions always eat their own children and the cancellers will eventually be cancelled. It’s just a matter of time.

Read more:

Is cancel culture a force for good? Our two columnists go head-to-head

‘Comedy is about taking the toxins out of pain’: how the future of jokes is tied to taboo

'Postmodernism gone mad': is academia to blame for cancel culture?