'We take care of family': When accessible travel is hard to find, families forge their own paths

"Traveling with disabilities" is a 10-part series focusing on the experiences of travelers with disabilities. This is part of our continuing mission to highlight underrepresented communities in travel. If you'd like to contribute to our reporting and share your experience as a source, you can fill out this quick form.

Marta Rivera says she's "not a very strong person," but the longtime Army wife and mother of twins could always find extra strength for her own mom.

"With my mom, it was like I got these superpowers," she said.

Like Rivera, her late mother, Luisa Lee, had multiple sclerosis. MS causes the body's immune system to attack the nervous system and disrupt brain signals. Symptoms can vary from temporary pain to permanent paralysis.

Lee was quadriplegic toward the end of her life and also had severe osteoporosis, weakening her bones. Rivera was her full-time caregiver. When they would travel, Rivera would sometimes have to carry her mom down tight airplane aisles to the restroom "like you when you're crossing the threshold, when your hubby picks you up," as fellow passengers stared.

Travelers with disabilities are used to the looks and lack of help from others. They and their families are used to forging their own paths through a world that isn't always accessible.

'I'M OFTEN FORGOTTEN': How travelers with disabilities prepare

THE TRAVELERS YOU WON'T FIND AT AIRPORTS: Omicron impedes travel for people with disabilities

"More than 1 in 4 of the people in this country have some kind of disability," said Dr. Linda Williams, a clinical psychologist and founder and CEO of Invisible Disability Project, which serves people with "physical, mental or emotional impairment that goes largely unnoticed" by others. "You have a right to live fully and wholly and freely in a space."

"One thing that a lot of people forget is the dignity that is lost on people," Rivera said, reflecting on her mom's life before chronic disease took hold. "My mom served 24 years in the Air Force (and) during the Vietnam War. My mom was one of the few Latinas to earn the rank that she earned in the Air Force. So when I talk about a woman who is extremely proud ... it took every bit of her dignity to have me have to shower her, have to bathe her, have to do all that stuff."

Williams, who is visually impaired, says shame and internalized ableism are not uncommon among people with disabilities. To avoid embarrassment, she says people with invisible disabilities sometimes sacrifice or suffer in silence to pass as able-bodied. One of her hacks, when she can't read menus at restaurants, is listening to what others order and have what they're having.

"We have to be able to say 'I need an accessible space' and then we have to be able to define what that specific access need is," she said.

Accessibility is not universal: 'Different families have different needs'

Bethany Hildebrandt, a mom of three, is meticulous about planning for her family's needs. Her eldest, 15-year-old Kaylee, has cerebral palsy, among other medical complexities. CP is a group of brain-related disorders that impairs muscle control. While it can present in many ways, Kaylee's case is moderately severe and requires full-time wheelchair use.

"We do everything for her physically, so bathroom, showering, changing clothes," Hildebrandt said, adding that the joyful, empathetic teen's cognitive abilities are comparable to her peers and that she recently co-authored a book with her grandmother on living with CP.

TRAVELING WITH IBD: 'When you spend much of your life being sick, it's easy to develop FOMO'

Before any trip, Hildebrandt makes every effort to figure out how accessible the destination really is and finds specific details are rarely available, so when they travel, she tries to post reviews and share firsthand experiences and tips with other families through her website.

"Every corporation, they want you to know they're handicap accessible, but that's a wide range, and different families have different needs," she said. "It really does take me getting on the phone and hunting down managers and (saying) 'I need you to walk me through this.'"

According to the American Disabilities Act, all hotels built since 1993 must be accessible to people with disabilities, but that doesn't mean the right kinds of rooms are always available to people who need them.

Despite being assured multiple times that they would get what Kaylee needed for a recent trip, their family was given a hotel room with a bar in the shower.

"We don't need a bar," Hildebrandt said. "We need a roll-in shower, which is drastically different."

It took days of transferring between rooms to get the right one.

Being invisible: 'People have expectations that their disabilities aren't real'

Shannon Rosa's family has very different needs. Her 21-year-old son Leo is autistic, and her two other children are neurodivergent.

"(Leo) is a very high support person who needs one-to-one support with him all the time. He's partially speaking. He has (an) intellectual disability, so he has a lot of disabilities," Rosa said. "And when he was young, figuring out how to support him was hard because it's hard to access good information about how to support autistic people. So a lot of times people will try and force autistic people to do things that they think they should be able to do, like the most common example is (making) eye contact, but less understood examples are things like breaking routine, which is exactly what travel is."

She found talking to adults who are autistic especially helpful for her own understanding and now helps others as senior editor of Thinking Person's Guide to Autism.

Rosa says Leo enjoys the physical aspects of travel, like riding in shuttles, trains and planes on short flights, but they've largely avoided travel during the pandemic because he can't wear face masks for more than 30 seconds for sensory reasons.

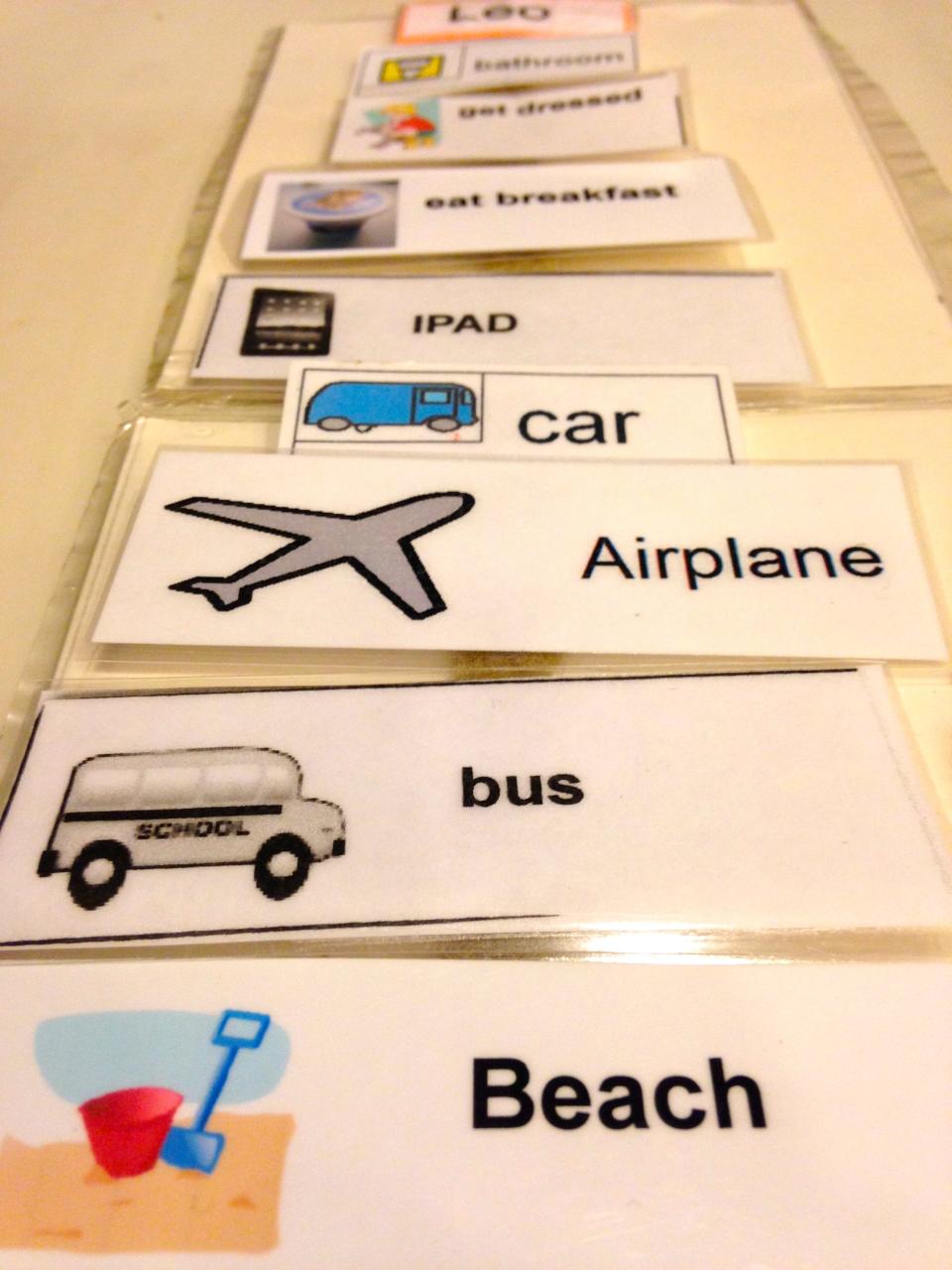

When they used to travel, Rosa used a visual schedule with images and words so Leo "can see what his day is going to look like."

She also looked for hotels with good noise protection and asked for rooms on the ground floor because Leo can be loud, and other guests have complained.

Rosa's other kids' disabilities may not be obvious to others.

"Because unlike their brother, my other children are both fully conversational and they're in regular classes and participate in society in a way that he can't, people have expectations that their disabilities aren't real," she said.

There can be a stigma for people with invisible disabilities.

"The classic example that's overused is disability parking," Williams said. "If I have a placard and I am parking in a disability space and someone sees me getting out of my car and I do not have a wheelchair and I do not have a walker, there is a lot of stigma ... 'How dare you take a parking place that does not belong to you?'"

'If you don't have a need for that stall, don't use it'

Hildebrandt and Rivera want people to understand that closer parking spots and larger bathroom stalls aren't perks for people with disabilities.

"There's a need that's being met there," Hildebrandt said. "Sometimes it's the difference in us being able to access the bathroom or not in a timely manner, which means the difference in us (needing) to change an entire wardrobe versus just being able to change and go."

"If you don't have a need for that stall, don't use it," Rivera added, thinking of her mom. "She was paralyzed from the neck down. She couldn't have control over a lot of stuff. But if she would say, 'You know, I feel the need to go to the bathroom' ... there was nothing more frustrating than to see someone who can ambulate walk out of that stall because she would have to wait to get in there."

Story continues below.

Reflecting on those experiences can raise Rivera's stress, but she tries to avoid it to keep her own MS from flaring up. Her illness impacts her vision and dexterity, which is not ideal for the chef and author behind the virtual cooking academy Sense & Edibility. When it gets really bad, Rivera has to use a wheelchair and avoids extensive travel.

"But if we relied on that, my mom would have never gone anywhere because she was always in a wheelchair when she came to live with us," she said. "We took her to the Grand Canyon. We took her to Puerto Rico. We took her to Yankee Stadium. We made sure that she saw everything that she wanted to see before she passed away, but it was not without a lot of obstacles."

TRAVELING WITH CANCER: 'The best part was watching everyone smile'

Some places are more accessible than others.

"Disneyland is a wonderful place because that's actually one of the few places that you see a huge amount of disabled people out in the world having fun and enjoying themselves," Rosa said.

Both Disneyland and Walt Disney World offer Disability Access Services passes that help guests with disabilities minimize the amount of time they physically wait in line for attractions.

Rosa also uses third-party crowd trackers to find low attendance days to avoid sensory overstimulation.

Before the pandemic, her family also enjoyed visiting family-centered resorts, where "everything is really easy."

"My son thinks it's the greatest idea ever that people can bring him french fries and pizza, and he can go swimming in the pool, and he can go swimming in the beach," Rosa said.

Hildebrandt's family hasn't been to the beach in years.

"Kaylee got to experience that when she was younger because for maybe 8 to 10 years we were able to physically pick her up," Hildebrandt said, but eventually Kaylee grew too big for that.

Very few places offer beach wheelchairs and even when they do, availability can be hit or miss, so for this season of life, her family just doesn't go.

"I often feel like (my younger kids) don't get the same version of a mom that they would have without having a sibling with medical complexities, but I just trust that ... there's not a singular event that is going to rob them of being happy in life and having their needs met and knowing that they are loved and taken care of and supported, " she said, adding that she hoped "they turn out being better people because of what they've gone through."

Rivera's 16-year-old twins are living proof of that.

"To this day, it just really touches my mommy heart when I see my children interacting especially with children that have disabilities," Rivera said proudly. "Raising my children with their grandmother, and not shielding them from the nastiness that is disease, has created very compassionate and sympathetic children who are going to become adults who do better, I hope, by people with disabilities."

That includes herself.

"We take care of family," Rivera said. "So if God forbid I get to the point where my mother was, I have no second thoughts that my children will take care of me because that's all they know."

Share your story

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Accessible travel: Disability access needs vary by family