How cars changed the lives of American women

During the golden age of TV sitcoms, the woman-driver joke became a script staple: “My wife is a careful driver. She always slows down when going through a red light.”

Cue the laugh track.

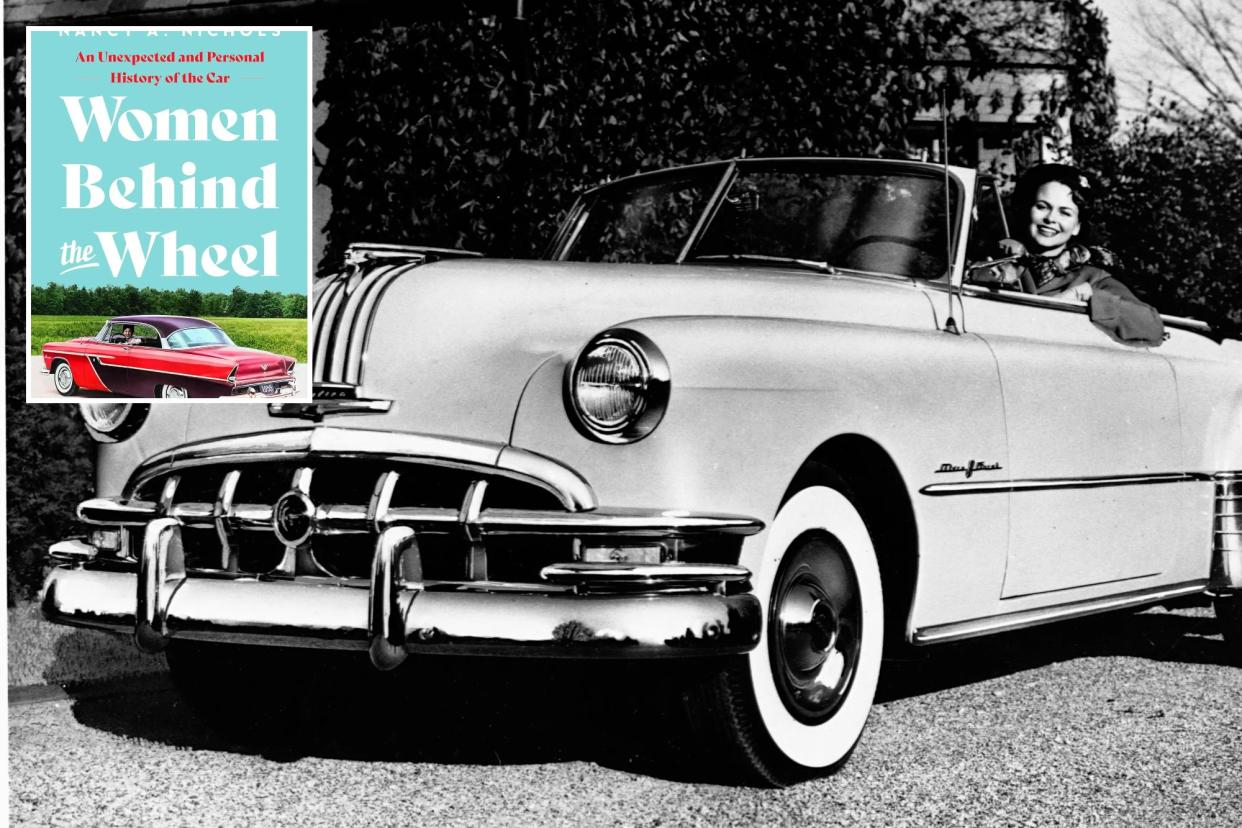

But journalist Nancy Nichols, daughter of an “alcoholic” used car salesman, has a far different and more serious take; in her new, highly readable part memoir, part car history, she makes clear that the woman driver and her experience behind the wheel is no laughing matter.

“Next to the birth control pill,” she observes in Women Behind the Wheel: An Unexpected and Personal History of The Car (Pegasus, out now), “no other technology has so greatly influenced the sex lives of women as the car.”

From classic muscle cars to electric vehicles, the car has helped define the modern woman since its invention in the 1880s.

When people think of the automobile, Nichols notes, they mostly think about men and speed, but a “pinup-mentality” rules when women and cars come to mind: Think bikini butt shots on hot rods, and perky brunettes and redheads lounging on auto shop calendars.

Esquire once described fellatio at high speed as “the pinnacle of vehicular sex acts.”

Bumper stickers and vanity license plates soon surfaced.

The author points to one in particular: “Ass, grass, or gas. Nobody rides for free.”

Nichols colorfully recalls her first car — a “beater” Chrysler Newport, “two-toned gold and brown” that her father got her “for a song,” when she turned sixteen in 1975.

She writes that she had learned to drive in high school, avoiding the “roving hands” of the male driving instructor.

“Mine was well-behaved,” she recalls, despite “stories abounding” of assaults on female learners by horny drivers-ed teachers.

But, oh, the wonderful sensation Nichols felt when she finally got behind the wheel alone for the very first time. “It was a relief to drive by myself . . . The car had gas, the weather was good . . . it was time to go.”

“Driving,” she intones, “freed” her from “the neglect, boredom and abuse I found at home . . . it changed not only the parameters of my life — it changed my experience of life.”

And it was changing the landscape with more motorways.

As the author points out, the car helped to define modern American womanhood – changing the nature of romance, and influencing child-rearing customs from the child hauling station wagon of the ’50s and ’60s, to the hatchback sedan of the 1970s and finally to the pervasive minivan of the ’90s — the universal “mom mobile” — perfect for hauling cargo and kids.

It also became a mobile bedroom and warning bumper stickers surfaced: “If it’s a rockin’, don’t come a knockin’.”

Chrysler chairman Lee Iacocca introduced the first minivan in 1983 saving the Chrysler Corporation from bankruptcy — and selling 200,000 units that first year — with women being the prime customer.

The minivan became the family second hauler and, according to the author, “fueled women’s already hectic lives.”

While Nichols got hooked on Honda’s new hulking Honda Pilot SUV introduced in 2003, she acknowledges that she was “just another mother participating in the great consumer lie that is car culture” — new models, less reliable cars and robust pitches to the consumer to constantly upgrade — “trade-in and trade-up.”

When Nichols eventually watched her Honda hauled away on a flatbed – its engine mounts so rusted it veered unexpectedly in a different direction on the road – she chose another Japanese brand, the tough-looking, dependable Subaru that came with its own curious backstory: it was identified with a particular buyer, lesbians.

According to the author, Subaru was the first auto company in the US to focus “a robust sales pitch on gays,” with a particular focus “on gay women.”

The research found that “lesbians were already buying Subarus in large numbers.”

When Subaru held a focus group in the bucolic Massachusetts town of Northampton, once described in a supermarket tabloid as “Lesbianville USA,” because of its large gay female population, all the potential car buyers who showed up were identified as lesbians.

Moreover, writes the author, Subaru, seeing a big moneymaker, began using “coded words”and slogans in its advertising to lure in more gay women motorists: Some ads featured the blatant tagline “GET OUT and STAY OUT.”

Its double meaning — get out of the closet and stay out of the closet, and into a new Subaru.

Still, Nichols, who is straight, fell for what became known as her “Lesbaru” by gloating neighborhood boys.

Car manufactures, Nichols notes, also targeted gay men but rather than the Subaru, they “preferred” more masculine “Jeep Wranglers or BMWs,” writes the author.

The Toyota Prius, one of the first hybrids — powered by both gas and electricity to record-breaking fuel efficiency — came to signify the buyer who was educated as well as environmentally concerned, in other words those on the Left side of the political spectrum.

Early on, the unattractive little car with great gas mileage was dubbed the “Pious Prius” and ridiculed by right-leaning motorists

Observes Nichols: “Cars, even as they define us, seem to have a special ability to provoke derision. In the end it doesn’t matter what kind of car you drove — “Your last ride is always in a Cadillac” — a big, black hearse.