Chanel’s Métiers d’Art Show Is All About the Magic of the Human Hand

Three weeks before the Chanel Métiers d’Art show in Manchester, England, the luxury house’s Paris workshops are a hive of controlled activity.

Since Karl Lagerfeld launched the annual display in 2002 as a way to showcase the know-how of its specialty ateliers, the fashion house has ramped up its commitment to craftsmanship.

More from WWD

RELATED: Travel in Coco Chanel’s Cap-toe-pump Footsteps? Oui, Please.

Previously scattered in cramped quarters across the French capital, many of its suppliers are now housed at Le19M, a striking building designed by architect Rudy Ricciotti and located near Porte d’Aubervilliers, a working-class area north of Paris.

Meanwhile, Chanel continues to acquire suppliers to guarantee their future. Earlier this year, for instance, it partnered with Italian firm Brunello Cucinelli to buy a minority stake in Italian cashmere manufacturer Cariaggi.

On a crisp Friday morning in mid-November, the teams at Le19M are busy weaving, pleating and embroidering the exceptional outfits and accessories that will feature in the collection designed by creative director Virginie Viard, due to be unveiled on Dec. 7 in Manchester.

Aska Yamashita, artistic director of embroiderer Montex, says everything begins here, with Viard doing a deep dive with the artisans to gather inspiration for the show.

“I welcome her here at the showroom and we look through the archives to see if there are any samples of techniques she might want to incorporate in the collection,” says Yamashita, sitting in the room where some 20,000 swatches hang in large metal cabinets.

Lagerfeld’s right hand for more than three decades, Viard is intimately acquainted with all the different workshops. In addition to Montex, Le19M is home to embroiderer Lesage; shoemaker Massaro; feather and flower expert Lemarié; milliner Maison Michel; pleater Lognon; grand flou atelier Paloma, and goldsmith Goossens.

“She does the rounds of all the ateliers,” Yamashita continues. “Afterward, it’s interesting to see the mix of the different styles of each house and how we each give our own spin to the collection theme.”

Viard likes to riff on locations without getting too literal. Last year, the Métiers d’Art show was unveiled in Dakar, Senegal, resuming its tradition of landing in destinations as far-flung as Tokyo, New York, Dallas, Shanghai, Rome and Edinburgh, Scotland.

The designer has sprinkled references to Great Britain into past collections, both as a nod to founder Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, who popularized the use of tweed, and to her own rock chic aesthetic. But Yamashita keeps details firmly under wraps, especially since she’s only glimpsed a portion of the final looks.

“We often work on sections of an outfit, so we don’t know exactly how it will look in the end and what different materials will be used. That means the show is a moment of discovery for us too,” she says.

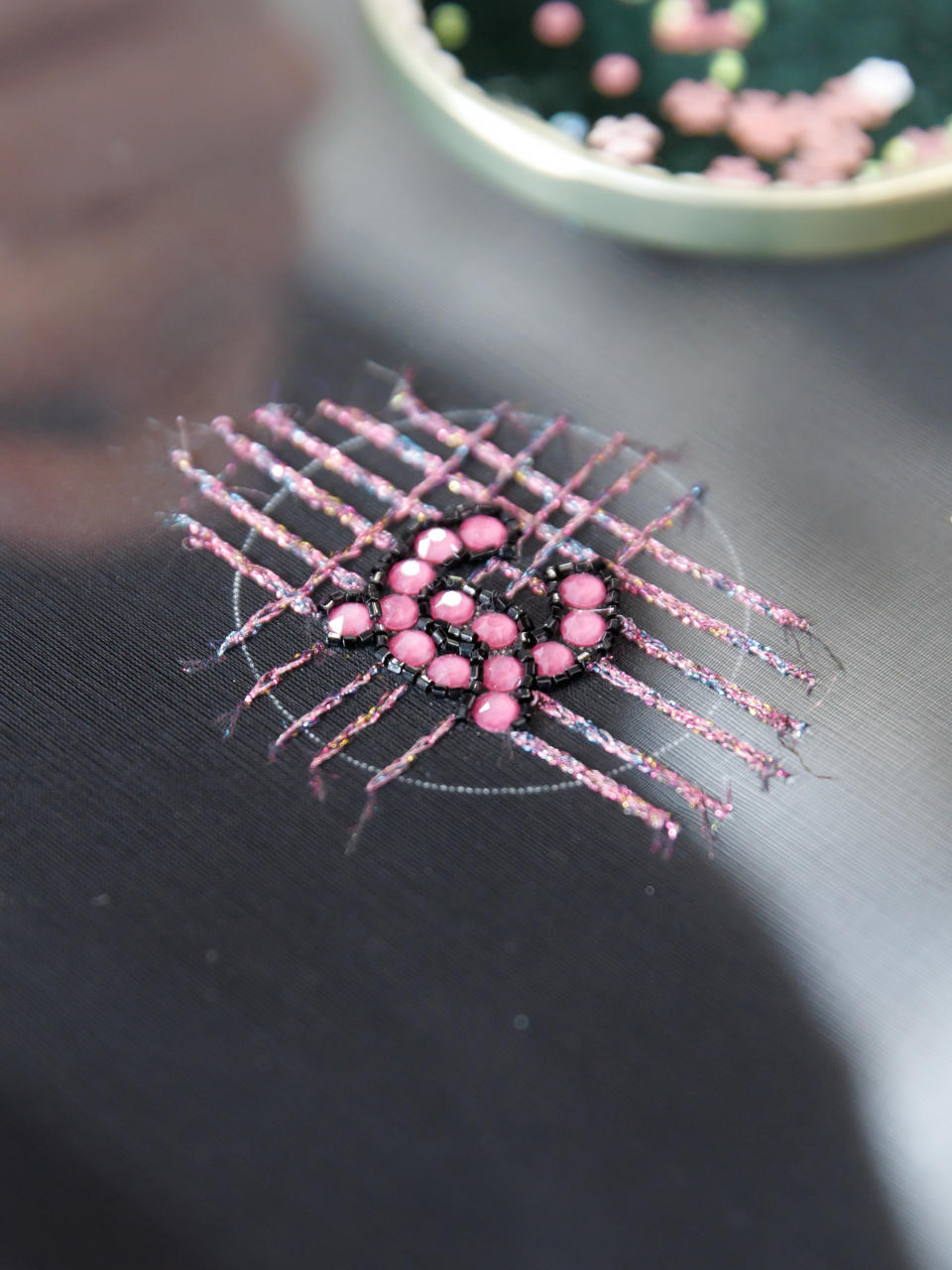

Artistic director of Montex since 2017, the embroidery specialist is known for her cutting-edge approach, incorporating unusual materials and combining techniques such as printing, machine embroidery, appliqué and laser cutting.

“These techniques are closer to jewelry,” she says in front of a table where a team applies silver metal rings onto black lace using pliers. “Just because we’re not working with a needle and thread that doesn’t mean it’s not embroidery.”

At Lesage, too, everything starts with the human hand. Anne-Lise Spivac, one of four textile designers who develop the house’s tweed fabrics, likes to design on paper, then weave a sample on a manual loom, noting down detailed production notes as she goes.

Her hands flitter across the loom, flipping levers as she shuttles threads back and forth. Spivac works with everything from plain wool or cotton yarns to printed ribbons, frothy woven or knotted threads and tiny floral sequins inspired by the house’s signature camellia.

“It can feel like there’s a lot going on. There can be ribbons, yarns, sequins and pearls,” she explains, adding that she’s even used zipper tape and rubber bands. “We try to make it sophisticated by mixing a lot of very different materials but always keeping it light.”

The drawings are designed to be easily converted into pixelized information, but when it comes to manufacturing, the trick is to make the end result a little irregular to give the impression of a handwoven fabric. “A machine is a machine, but we try to maintain this illusion, this imperfection,” Spivac says.

For Yamashita, the Métiers d’Art collection transcends ordinary ready-to-wear.

“This collection is special because it’s designed to showcase our know-how and the result is still ready-to-wear, but it’s bordering on haute couture,” she says. “Sometimes the distinction is fuzzy, even for us.”

Best of WWD