Charlotte Perriand, Design Museum, review: the French queen of bold, electric, modern design

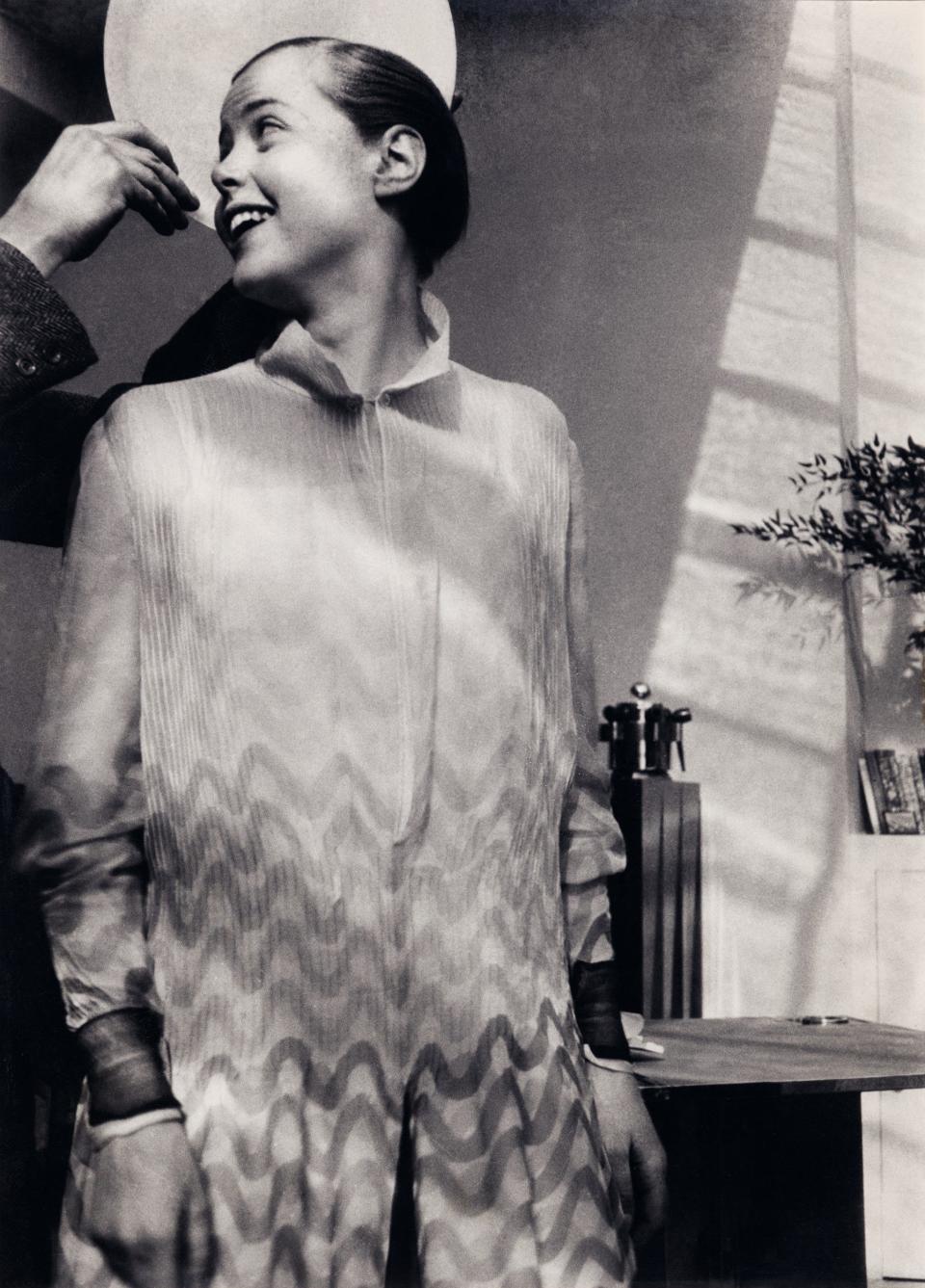

There is a photograph so enticing in this exhibition that when I reached the end I walked all the way back through, just to stand in front of it again.

Taken in 1928, it is of the French designer Charlotte Perriand, then 25 years old, with her colleague, the architect Le Corbusier. He’s out of shot, so we only see his tweed cuffs and hands holding a plate behind her head like a halo. She – with daring, gar?onne-style short hair – is laughing. How living, buoyant and assured she looks. Don’t you want to know her?

The picture was taken in Perriand’s Paris apartment, a loft she turned boldly modern with sliding doors and a tiny bar, complete with tubular steel stools. “Corbu” had seen that bar exhibited at the Salon d’Automne the previous year; it was why he’d hired her.

Photographs of her dot this graceful show at the Design Museum, and she gleams in every one. These, plus a generous display of her sketchbooks, convey her infectious vitality. No wonder every modernist clamoured to work with her.

Perriand is a hero in France, but if we know her at all in Britain, it’s only in connection with the tubular chairs she designed with Corbu and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret in the 1920s and early 1930s. Yet she remained influential until her death in 1999, working across interiors, furniture, buildings – even a ski resort.

She was wildly, searchingly modern, so seduced by engineering that she used car headlamps to light her dining room. Even so, as she aged – and as the militarisation of Europe tainted industry – it would be the natural world to which she would turn, lugging a sea-worn beach rock or a gnarly old wisteria back to her studio. “There is art in everything,” she said.

The show’s layout is by the Turner Prize-winning collective Assemble, and it is spot on. First, each plinth is a pile of silicate bricks in one configuration or another – a brilliant iteration of Perriand’s own penchant for modular furniture. Second, each room offers a picture window onto another, so that you instantly glean her unfolding style. In one, you can even try the furniture. I chose the Chaise longue basculante (1929), and wished never to get up. I fear I’d have locked myself inside House by the Water (1934).

From room to room, our sense of Perriand’s creative process builds. Everywhere you look, engineering is in poetic dialogue with natural materials: a chrome chair translated into rush and oak; sheet metal made to resemble a shadow. The detail of her thinking is cumulatively staggering: where in a room might the family want to eat breakfast? If she removed a table leg, how many more knees might jostle underneath?

The show’s feat is to see the world through Perriand’s eyes. Even a perfunctory wander will alter forever the way you see the chair you sit on, the window you open and the view beyond it.

From Saturday until Sept 5. Tickets: designmuseum.org; 020 3862 5900