Christian Bale's Chubby Dick Cheney Impersonation Is the Only Interesting Thing About 'Vice'

Prosthetics might work for the average screen lion-like, say, Gary Oldman, who won the Best Actor Oscar this year for donning a fat suit in Darkest Hour-but not Christian Bale. To play Dick Cheney, the political orchestrator plotting behind George W. Bush in Adam McKay's Vice (out Christmas Day), Bale stacked on 40 pounds of pudge. In a couple stray shirtless shots sprinkled throughout the film, we observe the man fully embracing his paunch. Gone are the toned muscles Bale built playing the Dark Knight in Christopher Nolan's Batman films, replaced by a quivering dough mound. It's a superhero's body gone to seed.

But that's just Bale being Bale. Over nearly 20 years, he's made a name for himself in part thanks to his willingness to mold his body like fleshy clay to suit the needs of his characters:

American Psycho, 2000: Bale worked with a personal trainer six days a week, several hours a day, to play Patrick Bateman, fitting for both the character’s daily life as a narcissistic investment banker and his side hustle as a murdering lunatic.

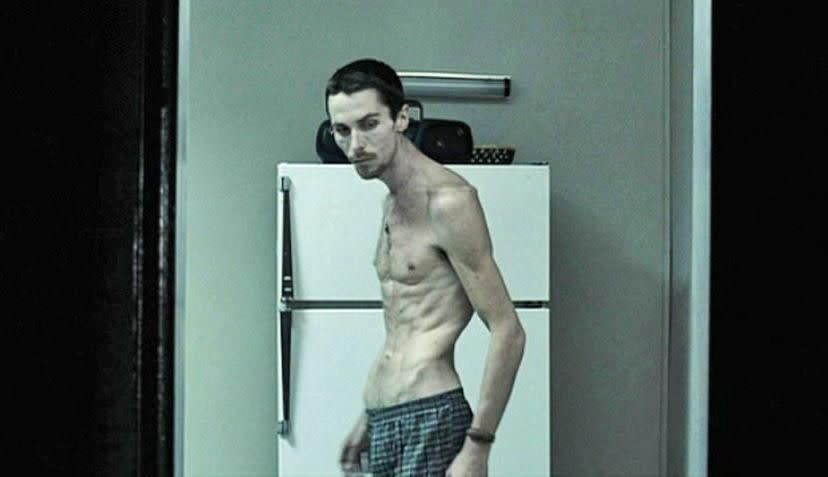

The Machinist, 2004: Bale withered away to play the scarily thin insomniac Trevor Reznik.

Batman Begins, 2005: Filming on the first Bat-Nolan movie took place half a year after The Machinist finished, so Bale mainlined food get his body mass back, then turned that into Caped Crusader muscle through an intense weightlifting regimen.

Rescue Dawn, 2006: Werner Herzog shot the narrative version of his 1997 documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly in reverse: His actors lost weight, then gained it back throughout production, which means that at the start, Bale yo-yo'd back down to skin and bones yet again.

The Dark Knight, 2008: More Batman, more muscle.

The Fighter, 2010: After taking so many unnecessary health risks for art's sake, Bale finally won validation for self-destruction with a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for The Fighter. Here, he played Dicky Eklund, the drug-addicted half-brother of boxer Mickey Ward. Bale apparently found dropping 63 pounds for the film easier thanks to his work on The Machinist.

The Dark Knight Rises, 2012: "I am the night."

American Hustle, 2013: Excessive weight gain sounds way better than excessive weight loss. For American Hustle, Bale feasted primarily on cheeseburgers.

Vice follows in the footsteps of American Hustle in terms of Bale's weight gain, but he'll have lost it by now: It's tuxedo season. He presents as portly on camera, but he needs to look svelte on red carpets. He'll probably win the Oscar. Vice is, after all, a movie built for Oscar dominance, a flashy biopic about an infamous figure in recent political history, and it demands its leading man transform from handsome to hefty. That's an awards-circuit slam dunk. Ultimately, Vice isn't a movie as much as a plea for accolades.

Vice starts in 1963 Wyoming during Cheney's dark days drinking too much, fighting in bars, and getting pulled over in the wee hours, all to the chagrin of his long-suffering wife Lynne (Amy Adams). The ignominy of Cheney's alcoholism is one thing, but what bugs Lynne most is his lack of drive. McKay's intent here is muddled. Either Lynne wants Dick to be the driven man she thought she married, or she's Lady Macbeth and she wants him to attain political clout so she can revel in proximity to power. Vice expects the audience to believe Cheney put the United States over a barrel to save his marriage, as if that's enough of a peace offering to encourage our empathy.

The movie's a true story, the opening title card professes-"as true as it can be given that Dick Cheney is known as one of the most secretive leaders in history." But Vice cares more about his crimes and misdemeanors committed in public than his secrets. The Cheney of the movie has good intentions that mutate into naked lust for control, his every move designed to secure powers not normally afforded to the position he holds, whether that’s Gerald Ford's White House chief of staff, George H.W. Bush's Secretary of Defense, or, most significantly, Dubya's VP.

As Vice and McKay concede, Cheney kept to himself and carefully deflected political scrutiny. There's little the film tells us that can't be gleaned from Google searches or Wikipedia. It's political CliffsNotes delivered with smug self-congratulation. McKay peppers the film with embarrassing fourth-wall breaks, from Naomi Watts' recurring appearance as a Fox News anchor who recaps Vice's plot to Bale's smarmy final speech as Cheney directed to the camera. McKay "exposes" what the world's known about Cheney since forever with the intense self-awareness of Jean-Luc Godard or Michael Haneke and none of their artistry. (This is in keeping with The Big Short, McKay's 2015 financial crisis drama, though that was comparatively restrained.)

If anything, Vice feels like a vessel for Bale's stunt performance. Work like this never actually feels like performance, though, and instead reads as performative. It's mimicry. Good mimicry, in fairness. Bale emulates Cheney's mannerisms-his cocked head, sideways smile, gravelly, rasping speech-perfectly. The trick works. We think we're watching Cheney and not the Welsh-born thespian. But there's no character in Bale's work, just a collection of ticks meant to add up to what too many viewers believe is great acting.

Winter movie season inevitably brings a deluge of dreadful issue-based movies that turn subtext into text and jam sentiment down viewers' throats. Vice is no exception. It's just more pronounced, more assertive, more insistent of its own worth. Satire doesn't need to be this blatant. Armando Iannucci's The Death of Stalin made old history into a relevant political parable without trying to so explicitly connect dots. But McKay can't help swinging for the obvious punchline, just like Bale can't resist an opportunity to shift shapes. The combined effect is bludgeoning. Who is Dick Cheney really? Maybe that's not a question worth asking. Maybe we won’t like the answer. Either way, we don't get one.

('You Might Also Like',)