Confused about coronavirus testing? What antibody and active-infection test results can tell you

As much of the country begins reopening, in some capacity, following the coronavirus stay-at-home orders, many people are wondering where to turn for indicators on whether or not it’s safe to gather with friends and family.

But if it’s testing you’re looking to — either the active-infection nose swab or the COVID-19 antibody test, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called out this week for high levels of inaccuracy — you might want to shift your focus, say experts.

“There’s no one test that’s going to give anyone enough security to feel like they can go and hug a loved one and not pose a risk,” Dr. Kavita Patel, a Yahoo Life Medical Contributor and non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institution, tells Yahoo Life. “It’s more a question of how much risk you’re willing to take, since there’s no test that’ll give you enough clearance.”

So, then what is the purpose of existing coronavirus tests? Who should get them and why? And what should those who get tested do once they have results? Yahoo Life consulted with three experts for the not-so-simple answers.

COVID-19 active-infection test: What is it?

This tests for the genetic material of the coronavirus, based upon a swab of mucus taken from one’s nasal passages.

The results present “just a snapshot of that moment in time,” says Patel. That’s because you can test negative one day and positive the next, because you contracted it after accurately testing negative. “It’s why people like the vice president get tested every single day,” she says.

There are other drawbacks too, explains Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. “It does have limits of detection, so technically you could be incubating the virus and test negative one day — and then the next day you’ll test positive, as the viral load in your nasal passages has reached a level of detection for a test.”

For those reasons, a negative active-infection test “is not a bill of health that you could take going forward,” he stresses. “You’d have to be continually tested for it to serve that purpose.”

As Patel stresses, “One test gives you that one moment in time. So maybe before getting on airplane… But it’s never going to be that silver bullet.”

So who should get this test?

In addition to heads of state and people about to board airplanes, the nose swabbing should pretty much be left to individuals who are experiencing symptoms, who are involved in an outbreak investigation or who are getting a presurgery screening from their health care provider.

“Say, for example, somebody’s coming in to get their hip replaced,” says Adalja. “[The hospital will] do the test one or two days prior and use it to have a reasonable degree of safety when they bring that person in for surgery. But everybody understands it’s not iron-clad.”

Still, if asymptomatic people infected with the virus can spread it unwittingly, shouldn’t everyone get tested regularly?

From a public health standpoint, the answer is probably yes, Yale School of Medicine infectious disease associate professor Onyema Ogbuagu tells Yahoo Life. But that’s in an ideal situation. “When there’s a shortage of testing, it makes sense to then use the limited supplies you have for people who are symptomatic,” he says, explaining the need for putting up some “guardrails” in order to prevent testing frenzy and to manage the flow of tests and treatment based on the reality of what’s available.

How might knowing the result allow you to change your behavior?

While a negative test should not serve as the green light for hosting dinner parties and hugging your elderly parents, a positive infection test can and should change your behavior — for both your health and the health of those around you. “If you’re positive, then it triggers the self-isolation. And the obligation would be to go back at least five days [and 14 to be more vigilant] and notify your contacts,” Patel explains. Knowing your status could have a bearing on your care. “You would monitor your temperature and keep a journal of your symptoms,” she says.

This week, the CDC clarified its guidelines for those who test positive for the coronavirus — including advice to isolate for at least 10 days. Therefore, knowing that you’re infected is helpful information.

The bottom line on nose swabs

“What it’s used for is to find out whether or not the symptoms that you have right now are caused by the coronavirus,” says Adalja. And a positive test, in turn, will help you figure out how to stay safe and how to keep those around you safe. This is particularly important for businesses and health care facilities that are trying to stop the spread of the virus.

COVID-19 antibody test: What is it?

These tests, explain Adalja, “will give you an indication that you were exposed to and infected with the virus sometime in the past — and that likely means that for a period of time, probably at least a couple of months, you’re unlikely to be able to be reinfected with the virus.”

But the specifics of that possible immunity are still unknown, he says, in part because the way you find out such information is by doing “a natural history study, where you follow someone who’s been infected over a year and see if they’re reinfected,” and the virus is still too new.

Ogbuagu stresses the importance of being open about that uncertainty. “We need to really express ... gaps in our knowledge about what the antibodies even mean. It just means your body recognizes a foreign thing and produces protein that bonds to the virus. Can they protect against reinfection? We don’t have all those answers yet. How much of an antibody is needed to prevent reinfection? How long does it work for? Nobody knows.”

Besides not knowing precisely what a positive antibody test even means, there are enough other caveats with the tests and their usefulness to make anyone’s head spin.

First, the market has been flooded with versions of this test that have not been granted approval by the FDA — which first allowed this through a small emergency window, but which has since reviewed and then yanked nearly 30 such tests off the market. Then, this past week, the CDC said that antibody tests, in general, could be wrong up to half of the time and are not accurate enough to be used for making important policy decisions.

“Serologic test results should not be used to make decisions about grouping persons residing in or being admitted to congregate settings, such as schools, dormitories or correctional facilities,” the CDC warned. “Serologic test results should not be used to make decisions about returning persons to the workplace.”

Patel believes that, in most cases, the antibody test is simply “not useful,” adding that, as a physician, she has not ordered such a test for anyone.

“I think the reason people are asking for it is they think [a positive result will mean] they are immune to it,” she says, “but we don’t know how durable it is or how long it will last.” She adds, “Let’s say the test is positive. I can’t even tell you the test we have is good. So it could give you a really false sense of security.”

So who should get the antibody test? And why?

People who live in hot spots, for starters, might consider it, says Patel, who stresses that, because of the way the tests work, they only have the potential for usefulness in place with a high prevalence, which leads to more accurate results. “The performance [of the test] depends upon the prevalence of the disease in the community,” she says.

“Think of it as a calibration,” explains Ogbuagu.

So if people living in a hot spot, such as NYC, want to see if they’ve had the virus in the event that it “might make you feel good mentally,” says Patel, then it could be worthwhile. Further, widespread antibody testing in such hot spots could also be useful “for surveillance,” and for informing reopening strategies. Because if you know, for example, that 30 or 40 percent of the city’s population has already been exposed, adds Ogbuagu, it might provide clues about how widespread the outbreak has been and how long it might last. Potentially, he notes, “it can lead to important policy decisions.”

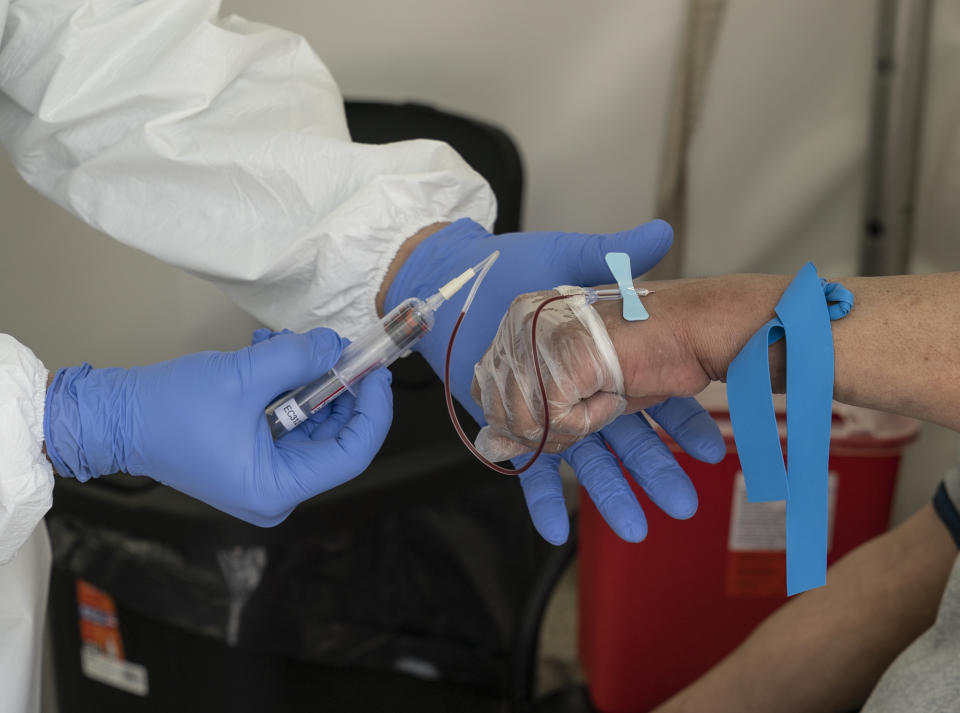

Other people who may want to get an antibody test, Ogbuagu says, are those who want to donate their blood as a potential treatment. “It’s important for plasma,” he says. “If someone had the infection and wants to donate blood to treat those with active infection, that’s one clear-cut scenario where testing makes perfect sense.” It could also provide useful information for health care workers who are returning to work after having been sick, he says.

When asked about the predictive value of the Abbott antibody test, which has received FDA approval, Mary Rodgers, principal scientist in Abbott’s diagnostic business, tells Yahoo Life, “Since the test became available, leading virology labs around the world have validated the test and demonstrated its high performance. A recent study published in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology found that Abbott’s antibody test had 99.9 percent specificity and 100 percent sensitivity for detecting the IgG antibody in patients 17 days or more after symptoms began.

How might knowing the result of an antibody test change your behavior?

That depends on who you ask — and on your personal tolerance for risk.

Adalja believes that knowing your antibody-test result (depending on its location and perceived accuracy) could indeed be a “part of the puzzle” for people trying to figure out when they can return to some degree of normalcy. Because he notes that when comparing two people, one with and one without antibodies, “I would say that the person without antibodies is more susceptible to infection, and that might be something that people use in their own risk calculation to decide what they want to do.”

For example, Adalja says, a person “may feel more confident interacting socially if they have the antibodies than if they don’t. But it’s all individual, and everyone has different rules for how they manage risk in their lives.”

Patel, meanwhile, is warier, believing that a positive antibody test “is not going to tell you anything that’s going to change behavior.” But she admits that the more we learn about the coronavirus, the more potential there is for that to change. “Even if you had a positive antibody test, I would still tell you to go visit grandma while standing 6 feet away and wearing a mask,” she says. “But that’s just for today.”

She adds that “what we know about the disease today is much more than we knew three months ago,” and while she personally wouldn’t interact with her elderly parents when there is not even an effective treatment available, that’s all for individuals to decide. “If you see your loved one now and you understand there is a risk, then you accept that risk,” she says. “If you’re going to wait, you have to ask yourself, what are you waiting for?” The answer will differ for everyone and could be anything from an effective treatment or vaccine to more accurate testing capabilities, none of which are here just yet.

“To put it bluntly,” Ogbuagu notes, “until we know more, I would say that even those with antibodies should act as if they haven’t been infected.”

For the latest coronavirus news and updates, follow along at https://news.yahoo.com/coronavirus. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please reference the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

How to maintain your physical and mental health during the pandemic

Taking care of a loved one with COVID-19? Here’s how to stay healthy

Q&A with Dr. Kavita Patel: How to keep your family safe and maintain your mental health

Read more from Yahoo Life

What's the difference between a 2nd wave and 2nd peak of COVID-19?

How to reclaim your sense of joy during the coronavirus crisis

Parenting expert says kids can start doing chores at age 2: 'It's almost never too young'

Want daily lifestyle and wellness news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Life’s newsletter.