How dangerous are 'spicy Latina' stereotypes?

After the publication of my recent essay titled “Is it OK to ask me ‘What are you?’” I received quite a bit of feedback — both good and bad — which was to be expected. One comment in particular got me thinking. A Latino man wrote to me directly on my Instagram, Nueva Yorka, expressing his disappointment in my article. While he admitted to not reading the entire piece, he felt confident in his assertion about me, saying, “Yeah you might be brown but you are white inside. Thank you.”

I loved the “thank you,” so I had to include it here.

I immediately felt defensive, angry, and, to be honest, hurt. I know, I’m so sensitive, right?! I’m a snowflake of a human being. As I tried to “get over myself,” I really began to wonder, as a Latina, what is expected of me both within and outside the Latinx community? How are we defining “acting white” and “being brown”? What are all these stereotypes and how dangerous are they?

The overarching theme is an idea of homogeneity in the Latinx community despite the fact that it is made up of so many different countries and cultural identities. Chief among these prepackaged ideas are gender characters such as the “bad hombre” and the “spicy Latina.” We can all easily rattle off a few commonly held Latina stereotypes. After a quick survey of men and women I’m acquainted with (of various ethnic backgrounds), the top slots went to: the maid, loud, curvaceous, emotional, accent (i.e., English as a second language), passionate, sexpot — basically anything attached to sex, sexy, or sexual.

These character tropes are widely portrayed and perpetuated in mainstream media, which is how we’re all acquainted with them. Arlene Davila, a professor at New York University professor and the author of Latinos, Inc.: The Marketing and Making of a People, describes the U.S. marketing machine as “an industry that only functions because the white advertising industry continues to ghettoize Latinas and POC (people of color) in their ranks and in their advertising. They have a huge impact because there are very few representations of Latinas that circulate in mainstream society.”

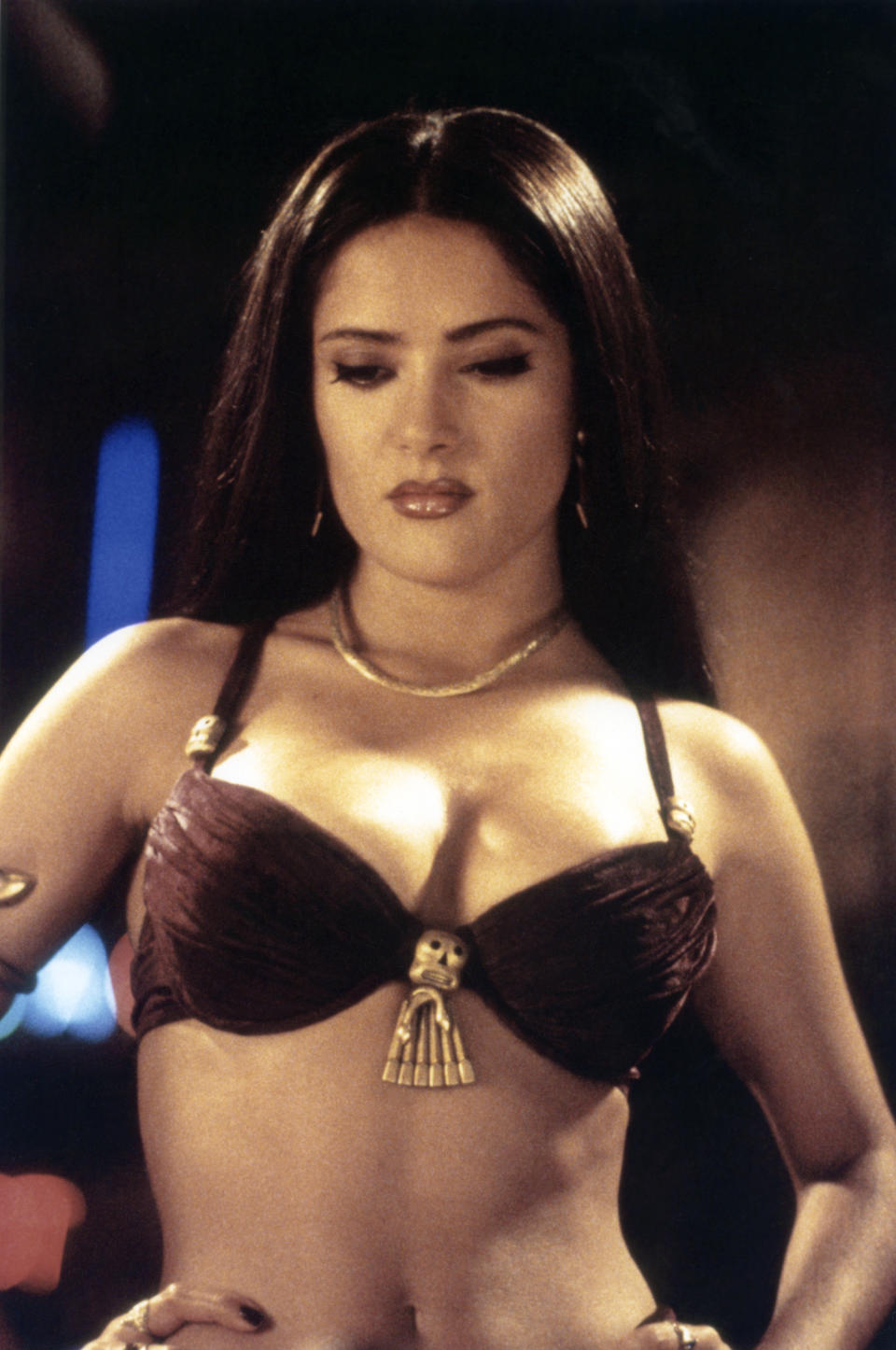

I must agree that in my growing up, I saw very few Latinas portrayed in American film, television, and advertising. I came of age in the ’80s and ’90s. The icons were Alicia Silverstone, Drew Barrymore, Winona Ryder, Gwyneth Paltrow, and the entire cast of 90210. We watched Friends, My So-Called Life, and Seinfeld. I never really saw many people on big or small screen who weren’t white. So when they did appear, it made quite an impression. In fact, I can recall the first time I saw Salma Hayek, an idol of mine, in From Dusk Till Dawn. I noticed her hair — wild, dark curls, just like mine. I noticed the curve of her hips — the severe slope — just like mine. It felt good to see it — a Latina on the big glitzy screen. For first time, I felt ‘a part of’ the commonly accepted hierarchy of beauty — like my particular “brand” of “exotic” was being widely represented and agreed upon as attractive. But, attached to this messaging was heavy, heavy sex.

This resonated with what I was seeing on U.S. Hispanic and LatAm programming as well. My parents watched Univision nightly, as well as a popular weekly game show called Sabado Gigante. It was outrageously commonplace to see a variety of scantily clad women draped onstage as if they were plants — heavily objectified and used as props valuated on their sex appeal and consumed playfully without a thought of an implication.

Even after decades, that imagery doesn’t seem to be changing. The effects took critical shape for me when I came into my body type and began being noticed by the opposite sex. The very first and most common descriptor for me was “sexy.” I got “sexy” constantly, at way too young an age, and I hated it. Moreover, soon after Salma Hayek made her mainstream debut, especially after Fools Rush In, I was compared to her constantly. And with this attachment came an expectation about my sexual prowess. Meanwhile, I was in no way prepared nor desirous to live up to the assumptions being hurled at me about my sexuality. In fact, the rules in my home regarding boys were positively military-like, making the Hoppe girls quite shy (and when I say shy, I mean terrified) about sex in general (sorry, sisters).

But I was also young and rebellious. Sure, I was scared of how I would be perceived, but I also wanted to indulge my need for self-expression, and I used fashion in particular for this. My best friend during my freshman year of high school, Tara, was a beautiful, waif-y blond. We shared a fervent interest in fashion and often went shopping together. We’d wear the same or similar pieces, but the response to each of us was so disparate! While the same clothes on her would be categorized as “cute” and “pretty” and she was labeled “best-dressed,” I was called a “slut” and accused of attention-seeking. Meanwhile, in my mind I simply preferred knee-high boots to Birkenstocks and, boy, did I love a tube top! It was the ’90s!

I understood I didn’t have the same bandwidth as my white peers, and if I didn’t want to be perceived a certain way, I had to temper my desire for self-expression. It affected my decision-making about how I was presenting myself — particularly what clothes I chose to wear and how I behaved with boys. My boyfriend once told me to change my dress before a school event because he was “not going to take J. Lo to the dance.” (This was right around the time Jennifer Lopez wore the now famous/infamous green Versace with the plunging neckline to the 2000 Grammy Awards.) It was clear that being Latina and my style of dress (obviously influenced by my Latinidad) were being conflated, which led to a negative conclusion. In fact, it specifically read: promiscuous. There were no actions to attach to these preconceived notions, only a likeness I demonstrated to an image — an image that is heavily reinforced in mainstream media and one that people agree to and project onto those they meet consciously or subconsciously.

Ana Flores is a media expert and a passionate advocate for gender diversity who has spoken on the topic twice at the White House. I recently sat down with the creator of the We All Grow Latina Network to discuss these stereotypes and the effects on young women. Flores explains, “I’m not sure there’s a culture within the major networks in LatAm and the U.S. to systemically change the propagation of stereotypes affecting Latinas. Many of the top shows in Spanish-language networks here and abroad still highly objectify women. Not only that, but the culture of telenovelas and brazen reality and gossip shows still dominates, positioning women as victims, overdramatic and emotional.”

Vanity Fair examined the topic back in 2015 with a cover story on Sofia Vergara and again in a shorter story in 2017. The article celebrated Vergara’s resourceful and “unapologetic” willingness to turn up the satirical volume on her body of work, noting that many white women such as Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, etc. are viewed as stereotypes as well. While I adamantly agree, the difference, I will note, is that throughout history we have seen many white women onscreen, and we’ve seen progression and variety increase in those images. The same cannot be said for women of color. Therefore, when the highest-paid actress on TV, on the nation’s most popular show, happens to epitomize the “spicy Latina” stereotype, it has a significant impact.

Flores, who spent more than 15 years as a producer creating content for U.S. Hispanic and LatAm networks, confirms that the effects of stereotypes on young women are quite powerful — and the media shoulders a large part of the responsibility. “Of course the stereotypes exist, but they’re amplified and propagated by the images and media girls and boys are constantly receiving,” she says. “If this is the image a young Latina is seeing that represents her, she believes that she needs to fit that mold of what’s expected of her. It’s our job as creators to amplify the stories of successful Latinas from diverse backgrounds.”

As we increase the quantity and prevalence of authentic portrayals of women of color, without obscuring our cultural differences, these stereotypes will lose their mass appeal. And positive qualities that I possess as a Latina will not be credited to the effects of assimilation and labeled contrived “whiteness.” Because what’s even more disturbing than not fitting the stereotypical criteria for Latinidad in America, is that when I demonstrate characteristics that do not mirror these commonly held ideas, I’m accused of not being myself. I’m accused of “acting white.”

A few months back, I was on a date with a very nice guy who I liked a whole lot. His ethnic background, for the record, is half-white and half-Korean. We were sitting legs intertwined on the same side of the booth, which I find particularly romantic, when I opened up about a challenge I was facing professionally. Bryan held my hand and responded without a thought, “Oh, don’t worry about it, you act white anyway.” When I asked him to explain what it meant to “act white,” he defensively barked, “Oh, God! Are you going to get all sassy Latina on me?!” punctuating the insult with a neck roll and a wagging finger.

Needless to say, the conversation quickly escalated and I never saw him again. I was shocked by his language because most people try not to use racist rhetoric on a third date — especially when aimed at your date — but his assumptions didn’t shock me. Sadly, I’ve heard it many times. And I don’t think the solution is to try to change closed minds such as his — although it still was important for me to treat him kindly, in the hope of inspiring compassion and open-mindedness in him in the future.

My focus today, most especially after my chat with Flores, is on being proactive. Instead of blindly blaming the system, we need to understand our role as the audience and entertain more substantial and complex stories from the POC perspective, as much and as often as possible. And while I can personally attest to the difficulty in publishing POC content in mainstream media, Flores has a wonderful suggestion. She says, “The problem is that media is still a game of supply and demand. So, in order to truly get network executives to want to invest in stories that elevate and inspire Latinas, we have to as a society consume and celebrate those stories. That’s why I believe online content creators are so important in moving the needle, because we have no boundaries to share our stories and truly start creating a culture that uplifts us.”

I’m a huge proponent of this strategy. Let’s call more voices to the table. I personally do not identify with today’s most popular Latina celebrities, such as Cardi B and Sofia Vergara, but that doesn’t stop public consensus from relating their images back to me — simply based on the premise that they’re Latina and I’m Latina. Therefore it is important to offer mainstream audiences more than what is entertaining — there’s a responsibility to tell a story that is true. Because the more we spoon-feed people lowest-common-denominator laughs, we make the door to progress and open-mindedness that much harder to open.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.