Decadent, prickly, and good in bed: meet the real Cecil Beaton

As soon as you begin looking into photography, or film, or theatre, or fashion, or design, or the Second World War, or the Royal Family, or in fact almost anything that happened in the 20th century, you meet Cecil Beaton. And then you go on meeting him, because his influence has been so far-reaching.

Over his near 70-year career, the British aesthete, who died in 1980, filled hundreds of sketchbooks, wrote hundreds of thousands of words, designed hundreds of costumes and sets and exposed thousands of rolls of film of such distinction that his thoughts and images have remained in almost perpetual circulation.

He was fuelled, he once said, by the fear of being ordinary. The idea that he might be thought of as such tormented him, as did his ambition, which was furious, all-consuming and made him, as David Bailey remarks, in a new documentary about Beaton, Love, Cecil, “a terrible social climber.”

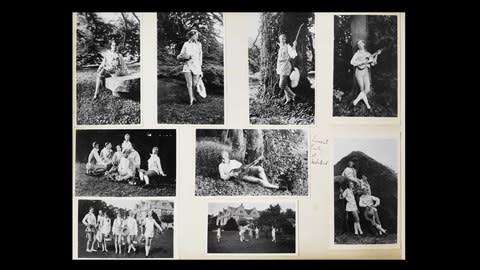

Climb he did, though, from the suburbs of North London to the country houses of England’s aristocracy, with whom he picnicked in extravagant costume on the Wiltshire downs, or to Westminster Abbey as a guest at the Coronation. Even, it is said, into Greta Garbo’s bed. “I'm told actually Cecil was quite good in bed with girls,” says the interior designer and socialite Nicky Haslam, in the film.

Love, Cecil, a confection of photographs, footage, interviews and passages from Beaton's own letters and diaries, read by Rupert Everett, is produced and directed by New Yorker Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who has previously made documentaries about fashion savant Diana Vreeland (her husband’s late grandmother), and about art collector Peggy Guggenheim.

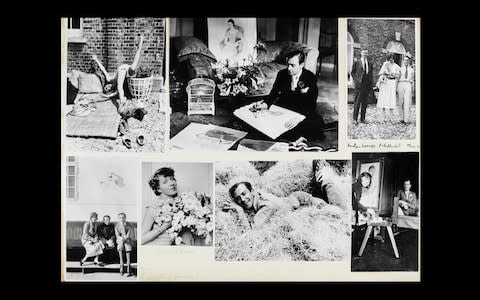

All three bring lost archival material to light, especially in the case of Beaton, where Immordino Vreeland unearthed both footage and persons not seen in decades. We hear from Beaton's butler Ray Gurton, for instance, recalling his time at Reddish Manor, in Broad Chalke, Wiltshire, which Beaton purchased in 1945 and in which he lived out his dotage.

Not that he really had a dotage - Beaton despised the idea of "old age" and fought to keep working as long as he was able. "The real Cecil would come out when he was home at Reddish," says Gurton, at one point, "in the garden with his old garden clothes on. He was happy. There was no grandeur. He really was himself, which was very nice to see."

Next we see a white-haired Beaton with his cat, Timothy. "Here's my little cat. He likes very much staying in the herbaceous border. Come on, Timothy, dear. Oh, I'm so pleased to see you. Nice cat. Timothy White. Timothy White."

Then there is the clip of the Bright Young Things in fancy dress, posing for the camera, which Immordino Vreeland tracked to the Mosley family and, most remarkably, an American film from 1929, the year Beaton went to New York for the first time and really very early days in terms of sound, in which he declaims his theory of beauty to camera. It's smug, abominably precocious stuff, and he was just 25 at the time, all elbows and wrists in his double-breasted suit.

Immordino Vreeland unearthed the reel in an archive in New York, after having read press clippings preserved by Beaton in his scrapbooks, in which it is very clear the Americans didn't get the "gag", as he called it. "No beauties here, Artist in Despair He's in a funk, you know", reads one. "N.Y. Debs 'Hideous,' says Artist Seeking Beauty," another.

“His reputation precedes him,” says Immordino Vreeland, speaking via phone from a canal in The Netherlands, where she is already at work on her next project. “I’d seen a side of him – we’ve all seen a side of him – but I suspected there was a lot more. I think most people only know the exterior Beaton, the one that was not that serious about things, it seemed, that was about decadence and fun, and his prickly personality, but what intrigued me, the more I looked into him, was his creativity, which was just astonishing. He had this mad, mad desire to create, and in so many different fields.

"This was somebody who had real gravitas, who had an ability to be a vibrant person from the 1920s all the way through until the Seventies. He stepped into every one of those decades and he made himself relevant. That’s why he makes such a good story - it's really the story of the 20th century unfolding before you. How many people today can you think of who are doing that? Who are capable of that? If you think about who is our Beaton, who is the Beaton today? I can't think of anyone."

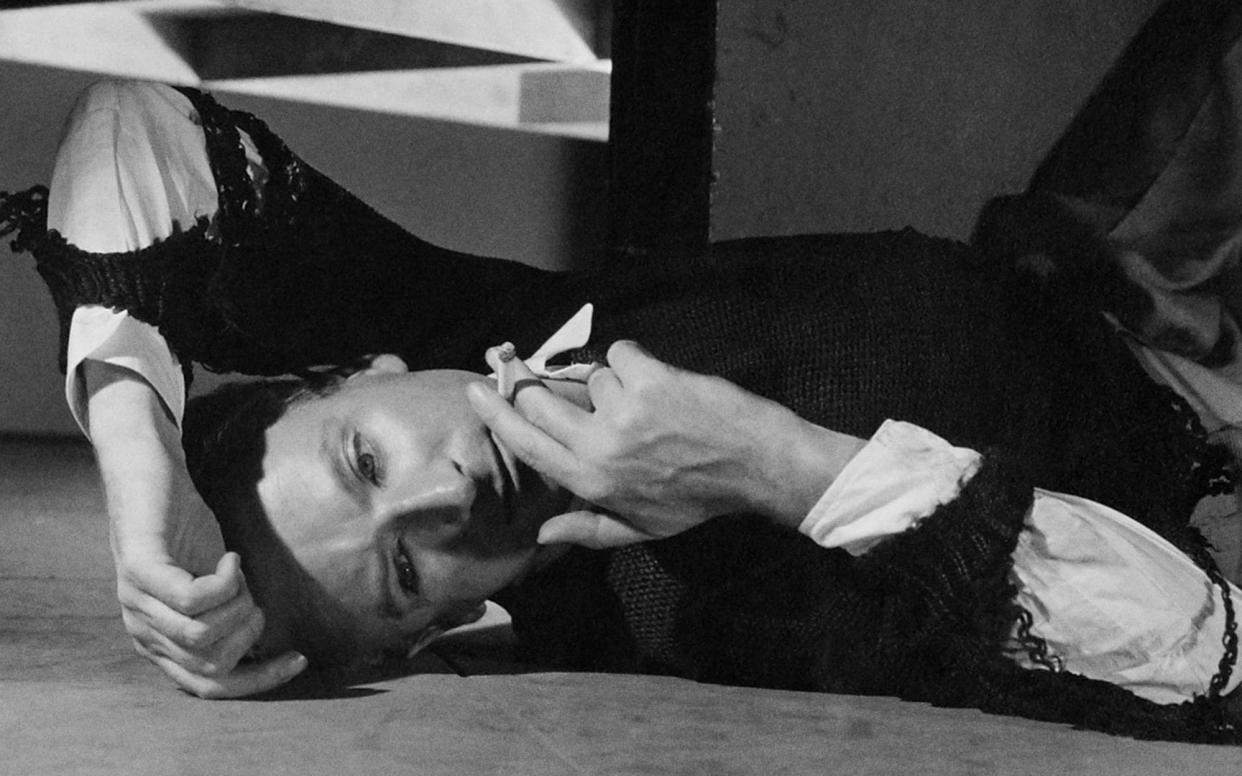

Fantasy and theatre were Beaton’s thing; his understanding of beauty second to none, informed by a magpie intellect capable of drawing parallels between Moroccan face painting and Spanish flamenco, for instance, or the faces of Isak Dinesen and Virginia Woolf. " I think beauty is there to be recognised," says Beaton, in the film, "I think it's terribly important for the photographer to approach the subject with a very definite point of view of his own."

"It's not the world as he found it," explains Philippe Garner, formerly head of photographs at Christie's. "It's the world as he transformed it, as he wished it to be... Seizing, freezing, holding that beauty, that glamour that idea, creating this Beaton universe."

"I think he was creating this theatre, this stage for us," adds Immordino Vreeland, "and as he was creating that, he was inviting everybody inside. What's fascinating about that is that he is still drawing people in in that way; he's still entertaining us."

Born in 1904, from his earliest years Beaton possessed, as he described, "a gnawing haunting for the stage," one that he cosseted at university by forming a Theater Club, designing scenery, and performing (in lieu of attending a single lecture). It later informed the innovative staging techniques he used in his photography, where subjects were photographed with their heads under glass domes, for instance or wrapped in cellophane or silver cloth, posed like statues against pillars and thrones.

It spilled over into the way he staged his own life, too, and the way he created a persona that suited his ambitions, to put himself into social class into which he felt he belonged. "Beaton was on the make from a young age," says Immordino Vreeland, "and his family were not going to be part of it. It made relations between he and his timber merchant father very strained, not helped when he caught Beaton trying on his mother's make up. Beaton's brother, Reggie, on the other hand, was Beaton's opposite and their father's favourite, and he always felt excluded."

The tangle of that relationship with his brother, who later committed suicide by throwing himself under an underground train (nobody seems to know why), and with his father, seems to have affected Beaton more than he might like to have admitted at the time. At one point, he describes looking through some of his old things, saying: "Some of the letters and documents make me sad. Some almost stop my heart beating. The telegram announcing my father's death. The piece of paper left on the hall table indicating that my brother Reggie was out.

"He would never come back to write that he was in... His suicide was the crowning blow to my father's life. I thought, dear Daddy, what a nightmare ordeal for you. Reggie was your favorite son. You'd been such friends. And I'm thinking now of all the days Reggie and I spent together. We grew up in great intimacy, fighting a lot, but really devoted. I feel full of regret and guilt for having been so selfish."

Watching the film, any fixed idea we might have had concerning Beaton wavers once, twice, again. We might start out thinking his life was charmed, for instance, his social circle glittering, his career always blossoming, never out of whack. He lived in a series of ravishing houses (one of which is now owned by the director Guy Ritchie, and parts of which feature in the film ), and decked himself out in the finest clothes (at one point, we are shown him repeatedly wearing the same hat, which he says he wears "because I think it has a certain Edwardian bravura."

But for every moment of fun (Beaton's vile summings up of his contemporaries, such as Katherine Hepburn: "A freckled, burnt, mottled, bleached and wizened piece of decaying matter" and Richard Burton "as butch and coarse as only a Welshman can be" are a particular highlight, as is Truman Capote on Beaton himself: "he seriously gathers enemies like other people gather roses"), there are 10 with a more a far more melancholy texture.

These are what linger with you when the film is over. Just how exhausting it must have been for Beaton to keep reinventing himself, to remain in the in-crowd, to never let a crack show in the life he had created for himself. How isolated he must have been - he never really had a relationship, though, Gurton says, there was "one regular black gentleman that used to visit quite frequently, but he was very discreet about it" - it was, after all, still illegal to be gay at the time.

"When you're making a film, you go through a process of liking, disliking, approving, disapproving of your character," says Immordino Vreeland, "but with Beaton, even during the moments when he was really difficult, where he acted badly, or incorrectly, or where he was misbehaving, I felt that it was because he was feeling insecure or an outsider. He hated getting old. He really hated it, and I think, though he had a lot of good friends, he was lonely. I cant imagine how he could work so hard and not have someone by his side."

Did she ever feel she got to see the real Beaton? "I think I did," says Immordino Vreeland, after a pause. "The person I discovered, he was so much more serious and he had so much more gravitas than I had expected. That person, he was was such a pleasure to get to know."

Love, Cecil is on release now, and will be on DVD from December 11