What 'Defund the Police' Really Means, and How It Could Be Effective

This feels like a turning point in American history. Hundreds of thousands of people are participating in protests across the country, and officials are already beginning to meet some of the demands of a nation outraged by racism and police brutality. The four now-former police officers involved in the killing of George Floyd, free men a little more than a week ago, today face charges of manslaughter and second-degree murder. Their city, Minneapolis, banned police from using chokeholds and neck restraints. California’s governor ordered that the state police stop training its officers in performing sleeper holds.

But we’ve been here before. Ferguson was just five years ago, and similar national episodes have placed racist policing under periodic spotlights for the past century. And reform efforts don’t necessarily move the needle. After all, New York’s police department banned chokeholds more than twenty years ago, which did nothing at all to save Eric Garner’s life.

After a first-of-its-kind 1922 investigation documented racist policing in Chicago, “a similar thing happens in Harlem a decade later, and another time in Harlem a decade later,” says Khalil Gibran Muhammad, a historian of race and criminal justice and professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. “It's like each moment forgot the last.” We talked with Muhammad about that history—and how this moment can be different.

Racism has long been endemic in American criminal justice.

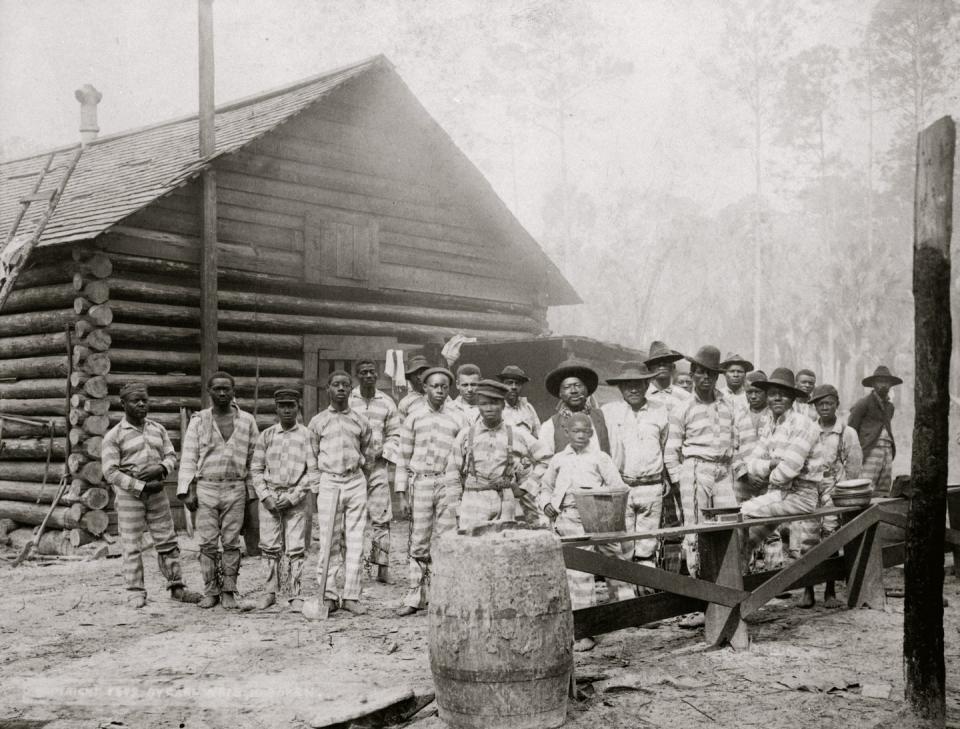

One of the earliest forms of policing to which black Americans were subjected were Southern slave patrols, groups charged with tracking Africans who ran away from enslavement and with thwarting slave uprisings. After emancipation, Southern states seized upon a loophole in the 13th Amendment, which banned slavery in the United States “except as punishment for crime.” Masses of newly freed black Americans were arrested for offenses as minor as “vagrancy” and pressed into forced labor. Before emancipation, a majority of Southern convicts were white. A few years after the Civil War ended, 70 percent were black. Prison labor helped build the American economy and infrastructure, with convicts working in mines and building railroads.

It’s unsurprising, then, that the 1890 census showed that blacks amounted to a third of all imprisoned people, despite being 12 percent of the US population. This data was used in statistician Frederick Hoffman’s influential 1896 article “Race, Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro” as evidence of inherent black criminality, rather than, as W.E.B DuBois put it in his review of Hoffman’s work, evidence that blacks and whites were “subjected to different standards of justice.”

“By the time we get to the Great Migration, most people took the evidence of the over-representation of African Americans in the criminal justice system as evidence that black people had a particular propensity for crime and could not truly be trusted with their freedom,” says Muhammad. This belief would inform the policing of black people around the country, ensuring that they would be subjected to more scrutiny and brutal tactics than other groups.

And just as racist policing is nothing new, examinations of its damaging effects are by now fairly routine. From the 1920s onward, investigative commissions “become management tools,” says Muhammad. “Civic leaders, state officials and sometimes federal officials say, ‘Well, let's study this problem.’ But the study of the problem always led to the same conclusion, which is that there actually is systemic racism.”

Take the 1968 Kerner Commission, which examined uprisings, often sparked by police brutality, that swept through black communities in the mid 1960s. The commission found that police and National Guardsmen had fired their guns recklessly at innocent people, and that black communities did not need more heavily armed law enforcement officers, but “a policy which combines ghetto enrichment with programs designed to encourage integration of substantial numbers of Negroes into the society outside the ghetto.”

“What did [then-President] Johnson do with the report?” asks Muhammad. “Nothing.” He declined to run for re-election, and was succeeded by law-and-order candidate Richard Nixon.

And there have long been piecemeal attempts to reform policing techniques. Louisville EMT Breonna Taylor was shot to death by police in March when plainclothes officers executed a no-knock search warrant on her home. Her boyfriend, a licensed gun owner, initially faced attempted murder charges for shooting one of the officers, before the charges were dropped amid increased national outrage around the case. Now, the ACLU of Kentucky is pushing for the state to end no-knock raids, in which police are not mandated to announce themselves or knock on a door before entering a home.

But no-knock raids have been controversial since the 1960s, and a law authorizing them on the federal level was repealed the following decade. Still, the practice is routine in most states, and victims of such raids include 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, who was shot to death by police in her grandmother’s home in Detroit in 2010, and a 19-month-old boy who spent time in a medically-induced coma after police in Atlanta threw a flash-bang grenade into his crib in 2014.

Many protestors and activists are calling to defund police.

We could already be on a path to more government investigations and pledges of reform—Ohio senator Rob Portman has called for a national commission on race that would not simply “restate the problem,” but that would “focus on solutions and send a strong moral message.”

“If you’re me, if you’re a professional historian weighing the capacity of law enforcement and the public to take on these changes,” says Muhammad, “you're very skeptical.” He often cites psychologist Kenneth Clark, who with his wife Mamie pioneered the “doll test” that became crucial to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling. In his Kerner Commission testimony, Clark said, “I read the report of the 1919 riot in Chicago, and it is as if I were reading the report of the investigating committee of the Harlem riot of 1935, the report of the investigating committee of the Harlem riot of 1943, the report of the McCone Commission on the Watts riot… it is a kind of Alice in Wonderland with the same moving picture re-shown over and over again, the same analysis, the same recommendations, and the same inaction.”

To Muhammad, history suggests that law enforcement is unable to reform itself, and expecting police to do so is like “asking the fossil fuel industry to solve the climate crisis.” He supports the growing calls to defund the police, an initiative that would “shrink the footprint of policing” by drastically cutting the $100 billion the U.S. spends on law enforcement every year and investing instead in other forms of public safety, from housing to mental healthcare.

Opponents to such a profound restructuring of policing cite concerns about how serious offenses like rapes and murder would otherwise be prevented or investigated. But arrests for violent crimes like these make up no more than five percent of arrests nationally. The vast majority of police arrests are for crimes ranging from drug offenses to failure to pay traffic fines—and supporters of the defund movement argue that communities would be better off if these issues were tackled by other kinds of civil servants, like counselors and social workers.

“City council members need to literally sit down and decide the range of things that police officers are to do,” says Muhammad. “Nuisance calls where police show up because someone's made a noise complaint, and now all of a sudden a black person has gotten beaten down by the police—take that off the list. Mental health visits or wellness checks for people who they might decide made them afraid, so they had to kill them—take that off the list.”

As for violent crimes, police critics point to the fact that the current system isn't all that effective at identifying offenders. Nearly 40 percent of murders nationwide go unsolved, and only one percent of rapes end in a conviction for a felony.

Even serious crime may effectively be tackled through non-police initiatives like Cure Violence, a non-profit on whose board Muhammad sits. The organization has lowered rates of gun violence through programs that include training community members as “violence interrupters” to mediate local conflicts and helping those considered to be at risk of committing violence access resources like job training and substance dependency treatment. One study found that when the New York Police Department briefly retreated from policing low-level offenses in the face of backlash over Garner's death, major crime actually fell.

In recent weeks, the prospect of defunding police departments has gained massive amounts of steam. On Sunday, a veto-proof majority of the Minneapolis City Council committed to dismantling the city's police department and reimagining its public safety infrastructure, declaring that "efforts at incremental reform have failed."

“Let's look at what a community needs,” says Muhammad, “so that it doesn't need policing.”

You Might Also Like