Directors of 2 Milwaukee Black history museums share important parts of Wisconsin's history

February is Black History Month, and Milwaukee has two institutions dedicated to preserving the stories of the people who have made Black history in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and the United States. Both museums were founded in the late 1980s by men who started collecting stories and artifacts on their own time with their own limited financial resources.

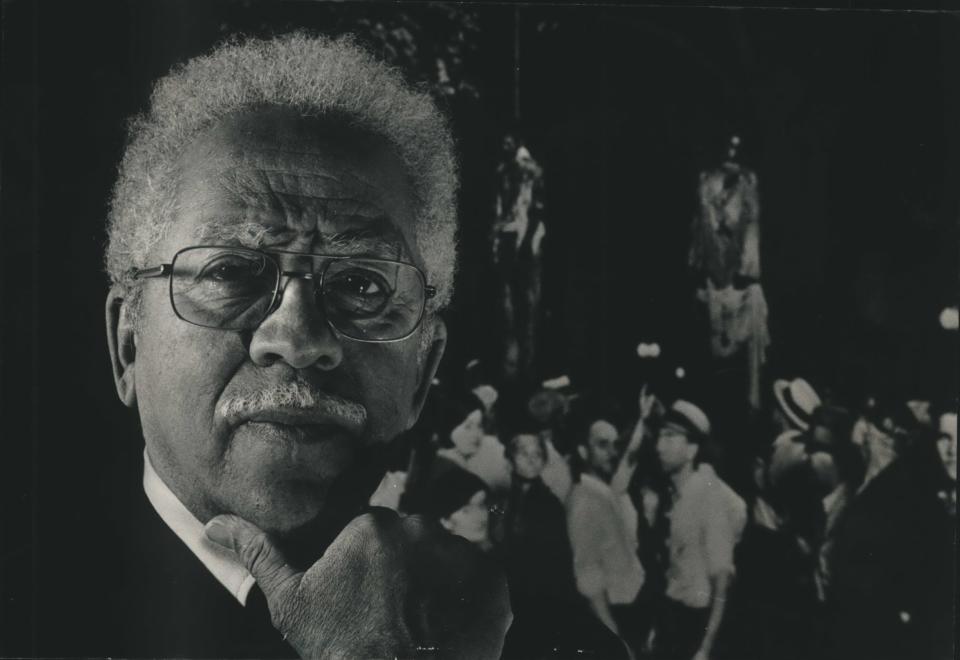

The Wisconsin Black Historical Society was started by Clayborn Benson, whose first decades-long career was as a photojournalist at WTMJ-TV. While still at that job, he embarked on his second career — collecting and preserving the history of Black Milwaukeeans and eventually acquiring the museum’s building at 2620 W. Center St. in 1987. Benson’s catalyst to start the museum was his production of a documentary called “Black Communities,” but his love of history started much earlier — in a barbershop as a child.

"My father would tell me stories of the people who lived here, and then, when he taught me to drive, we would drive past different places where things had happened in Milwaukee’s history," Benson said.

America’s Black Holocaust Museum was founded in 1988 by James Cameron, who survived a lynching in 1930 in Marion, Indiana, when he was 16 years old. According to the museum’s executive director, Brad Pruitt, the experience led Cameron to “want to better understand our collective history in order to be able to reconcile and heal.” When Cameron and his family moved to Milwaukee years later, he filled his basement with artifacts, books and photos related to Black people’s history and treatment in America. In 1988, he opened his museum in a storefront; then he bought a building from the city, which he remodeled and opened to the public in 1994. After his death in 2006 and the economic downturn of 2008, the museum closed. But a group of volunteers gave it new life when they opened a virtual museum in 2012, and when the physical building at 401 W. North Ave. reopened in 2022.

Here are some of the themes, moments and stories that are documented in these two museums about the city and state’s Black history.

There was slavery in Wisconsin

When people think about slavery, southern states — those that were part of the Confederacy during the Civil War — typically come to mind. But slavery happened in northern states as well, including in Wisconsin.

“Was there slavery in Wisconsin? Not in Milwaukee, but definitely in southwest Wisconsin,” Benson said.

This was true even after the 1787 Northwest Ordinance outlawed slavery in the newly incorporated western territory of the United States, part of which would eventually become the state of Wisconsin.

Benson said lax law enforcement allowed slavery to happen, especially in western Wisconsin during the lead rush. When people moved to Wisconsin to mine for lead, they brought approximately 100 enslaved people with them. Benson noted that Henry Dodge, the first territorial governor of Wisconsin, was among them, enslaving five people in Wisconsin. Most of the slaves in Wisconsin, including Dodge's, gained their freedom by 1842.

Lynching happened in Milwaukee

Pruitt noted that many people also think race-based lynching was a Southern thing.

But America’s Black Holocaust Museum — having been founded by a survivor of a lynching in Indiana — documents the history of lynching throughout the country, including in northern states.

“Dr. Cameron’s lynching was a spectacle lynching, with thousands of people in attendance; it was promoted, people were invited and photographs were taken,” Pruitt said.

A photograph of the two men who were lynched with Cameron, along with a crowd of white people in attendance, is featured on the cover of an early edition of Cameron's memoir, "A Time of Terror: A Survivor's Story"; it’s also part of an exhibit at the Black Holocaust Museum. Although it’s one of the most recognized lynching photographs in the world, captions under reprints of the photograph often fail to point out where it happened.

“Often, when the people using the photograph don’t know where it took place, they don’t cite a specific location in the caption,” Pruitt said. “But they will say something like, ‘Lynchings often happened in southern states,' under the assumption that this took place in the South.”

Although Cameron’s lynching took place in Indiana years before he moved to Milwaukee and established his museum, Milwaukee has its own past with race-based lynching.

In 1861, George Marshall Clark, a 22-year-old Black apprentice barber, was lynched and hanged at Water and Buffalo streets in the Third Ward.

On Sept. 6 of that year, Clark and James Shelton, another Black man, were verbally assaulted by two white men who were angry that Clark and Shelton were walking down the street with two white women. A fight broke out, and Shelton stabbed one of the white men, Dabney Carney, who died.

Clark and Shelton were arrested, and a mob of Milwaukeeans broke into the jail to attack the men; Shelton hid, leaving Clark as the only one to be beaten, given a show trial, and dragged by the mob to Buffalo Street, where they hanged him from a pile driver.

Milwaukeeans have been key in bringing attention to Clark’s lynching, with artist Tyrone Macklee Randle raising money for a grave marker for Clark that was installed at his grave in Forest Home Cemetery in 2021, 160 years after his death. Randle had learned about Clark during his studies at MIAD, and he was surprised to discover that there was no grave marker for Clark.

And, in 2023, the Milwaukee County Landmarks Committee, led by chairman Randy Bryant, finally installed a bronze marker in the Third Ward in remembrance of the lynching.

Wisconsin cities were part of the Underground Railroad

Abolitionists in Wisconsin helped escaped slaves with food and shelter as they made their way north to Canada on the Underground Railroad. Stations included the Tallman House in Janesville, the Milton House in Milton and “the biggest center of the Wisconsin underground railroad in Waukesha,” as described by an exhibit in the Black Historical Society.

Also in the display is a shackle and chain, representative of the slave trade, donated to the museum by a Wisconsin woman in January 2023.

“The white lady’s grandfather was an abolitionist in Wisconsin. She knew all about the enslaved people and where they came from. She told me roughly where her grandfather’s house was, how he had dug a hole six feet deep and escaped people would go in the hole, which was covered by wooden boards,” Benson said. “The lady didn’t want the chains anymore, but remains anonymous because she also didn’t want people to know her family participated in the Underground Railroad.”

Wisconsin abolitionists defied the federal Fugitive Slave Act

Waukesha — as well as Racine and Milwaukee — also make appearances in the story of Joshua Glover, an enslaved person who escaped from Missouri and ended up working at a sawmill in Racine in 1852.

In 1854, Glover’s former enslaver, along with federal marshals, broke into his home to arrest him. According to a display at the Black Historical Society, this arrest was legal because “the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed slave hunters to enter free states to arrest slaves and return them to their owners.”

A Milwaukee abolitionist and newspaper publisher, Sherman Booth, led a crowd of people to break Glover out of the jail he was being held at in Milwaukee. He was taken to a safe house in Waukesha and given help to escape to Canada.

Booth was convicted in a federal court for defying the Fugitive Slave Act. The conviction set off protests, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court became the first to declare the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court would overturn the state decision, the event brought fame to Wisconsin abolitionists as the Civil War approached.

Black men in Wisconsin were denied the right to vote for nearly two decades after they legally obtained it

Black men weren't given the right to vote when Wisconsin became a state; however, Wisconsin voters could give groups of people the right by referendum.

According to University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of Afro-American studies Christy Clark-Pujara, the disenfranchisement of Black people led to a mixed bag in Wisconsin in terms of Black rights: "In the mid-19th century, fugitive slaves passing through Wisconsin were often met with assistance, while Black permanent residents were marginalized," Clark-Pujara said.

In 1849, a referendum to give Black men the right to vote passed; outlandish rationalizations were employed to try to deny them that right, including a convoluted argument that because a majority of people who voted in the election as a whole that day hadn’t voted on the question of Black suffrage, the referendum results didn’t actually count.

Benson said these efforts to disenfranchise Black people due to racist loopholes, justifications and restrictions foreshadowed machinations like poll taxes and tests given only to Black people before they were allowed to vote, “and a lot of ways Black people are disenfranchised still today, like gerrymandering and voter ID laws” that disproportionately prevent Black people from voting.

With the result of the 1849 referendum in dispute, two additional referendums, one in 1857 and one in 1865, were held but failed to pass. But in 1865 a Black Milwaukeean, Ezekiel Gillespie, sued after he was not allowed to register to vote. Gillespie’s lawyer, Byron Paine — who had also argued against the Fugitive Slave Act in the Joshua Glover case — claimed that Black people’s right to vote had been granted in Wisconsin after the 1849 referendum, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court agreed, finally enshrining Black men’s right to vote in the state constitution.

In the fight to desegregate schools, Milwaukeeans got creative

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that separate schools for Black and white students were inherently unequal, and that U.S. schools had to be desegregated.

White citizens and government officials across the country fought the ruling, some by outright refusing to let Black students enter formerly white schools, and others in more subtle ways. Benson described these more subtle measures, such as giving Black students older textbooks or teaching them in segregated trailers on school property, as “cheating on Brown.”

In Milwaukee, Black lawyer Lloyd Barbee and the NAACP fought against city policies that resulted in de facto segregated schools. For example, students were required to attend schools in their neighborhoods, which, due to housing discrimination, were segregated. Activists also fought the practice of intact busing, where entire classes of students and their teachers were bused to other schools. The practice technically resulted in desegregated school buildings, but the bused students were not integrated into the receiving schools' classrooms. After marches, school boycotts and the establishment of freedom schools for Black students who were boycotting Milwaukee Public Schools, Barbee sued MPS.

After a judge ordered Milwaukee to desegregate its schools in 1976, Barbee and integration advocates worked with the district to create the Chapter 220 plan, which encouraged white suburban families to send their kids to MPS schools, many of which were turned into specialty schools for different subjects and curriculum — also called magnet schools.

Civil rights activists' fight against housing segregation included 200 consecutive nights of marching in Milwaukee

The Milwaukee area is often counted among the most racially segregated metro areas in the country. Much of that segregation can be traced to racist housing practices, such as redlining policies that meant houses in Black neighborhoods couldn't get insurance and banking discrimination, which prevented Black people from securing home loans. Also, restrictive covenants prevented white people from selling their houses to Black people. Many of these restrictive covenants can still be found on Milwaukee-area property deeds. Although the 1968 Fair Housing Act made them illegal, several local governments have passed resolutions repudiating the covenants.

Milwaukeeans have worked to combat racist housing policies in a variety of ways. Wilbur and Ardie Halyard opened the city's first Black-owned bank, Columbia Savings & Loan Association, in 1924, which was one of the only financial institutions that would lend money to Black people to buy homes.

Alderwoman Vel Phillips — who was the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin law school, the first Black person and woman to be elected to the Milwaukee Common Council, the first woman judge in Milwaukee and the first Black judge in Wisconsin, and the first elected secretary of state who was a person of color — introduced a bill to outlaw housing discrimination in Milwaukee in 1962. The bill failed, and would continue to fail as she reintroduced it three more times between 1963 and 1967.

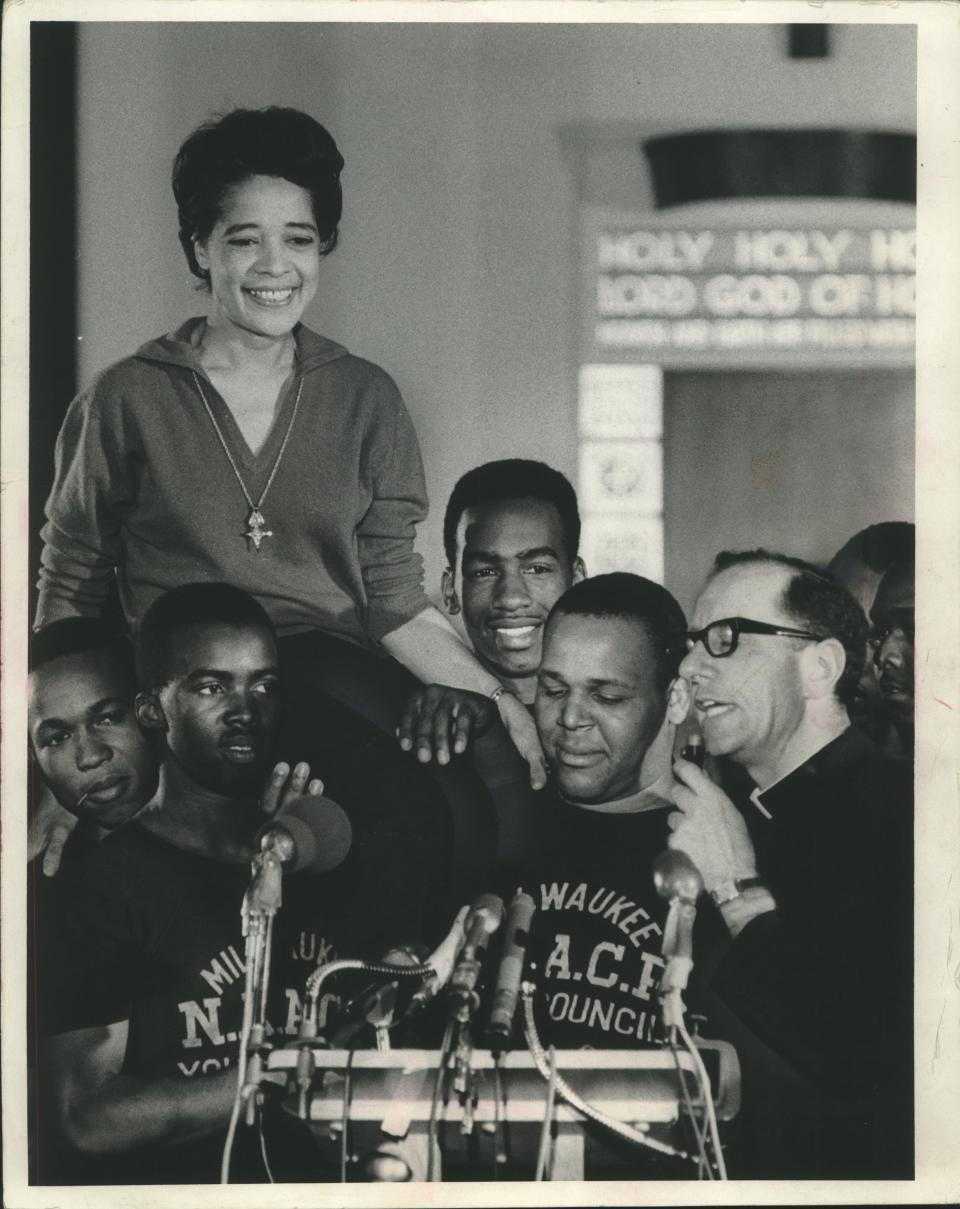

That's when Milwaukee's famous open housing marches started. Civil rights activist Father James Groppi organized members of the NAACP Youth Council to march from the north side of Milwaukee to the south side over the 16th Street bridge for 200 consecutive nights. Marchers were subjected to racist taunts, heckling and violence.

Shortly after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination on April 4, 1968, the federal fair housing act was passed. Then, on April 30, the Milwaukee Common Council finally passed its own open housing ordinance.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Important moments in Wisconsin and Milwaukee Black history