How ‘the dirtiest, sorest, most bedraggled cast in movie history’ made The Poseidon Adventure

When a young Ben Stiller told Gene Hackman that he adored The Poseidon Adventure, a movie that inspired him to be a filmmaker, the grizzled veteran actor fixed him with a stare and muttered, “Oh yeah. Money job,” before striding away. Hackman also dismissed his contribution to the double Oscar-winning film saying, “when I was working on it, I was kind of ashamed of myself.”

While filming The Poseidon Adventure, which had its premiere on December 12 1972, Hackman aggravated an injury to his right knee (a joint with metal pins in it, following a motorbike crash 30 years before) and his knee had to be drained three times during the production. It’s perhaps no wonder that he refuses to sign posters of the disaster movie when approached by fans.

Hackman was not the only luminary to be hurt making the highest-grossing film of 1973: Ernest Borgnine strained back muscles pulling on heavy ropes and had to wear a corset for the rest of the shoot; Jack Albertson suffered a head laceration and Stella Stevens scalded her backside on a hot pipe. The copious amounts of water (nearly four million gallons were used in all) left some of the cast with painful inner earache.

As well as the hurt bodies – from the explosions, jumps, fires, smoke, steam and broken glass – there were plenty of hurt feelings on set, and for years afterwards revelations of bitter rows, insults, rivalries and recriminations poured out from the cast of a movie that grossed more than $125 million worldwide and ended up spawning fan clubs, cinematic and television sequels and regular cruise ship tribute celebrations.

The film was an adaptation of a story inspired by the journey author Paul Gallico took in 1937, when the R.M.S. Queen Mary turned on its side in huge waves. Gallico’s 1969 novel was centred on a group of passengers desperately battling to escape from a capsized liner. Gallico led a curious life. As a young sportswriter, he challenged world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey to spar. “What’s the matter, son, doesn’t your editor like you anymore?” quipped the boxer, who toyed with him for one minute and 37 seconds before knocking him out. “There was an awful explosion within the confines of my skull and I was stretched out colder than a mackerel,” Gallico recalled.

After becoming a fiction writer, the New Yorker moved to England and lived with a great Dane and 23 cats in the Devon seaside town of Salcombe. The four-times married author became close friends with Ian Fleming, who later thanked Gallico for the encouragement he gave over Casino Royale. Gallico said the torture scene in Fleming’s James Bond debut, “beats everything I have ever read” and told him to publish such a clear “knockout”. Fleming later thanked his friend for “spreading his wings over my first-born”.

Although Gallico had huge success with his novel Snow Goose – and the 2022 film Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is based on another of his books – his personal assistant in Salcombe later recalled him saying, “I’m a rotten novelist. I just like to tell stories.” It’s not an opinion JK Rowling shares. In 2000, she told NBC: “I’m sorry Gallico’s not more fashionable now – he’s a great writer.”

At 72, looking for a new idea, the former war correspondent and film critic recalled his near disaster at sea. He spent months doing extensive research to make his fictional S.S. Poseidon (named after the god of the seas in Greek mythology) credible. And he came up with a truly dramatic, explosive yarn. Although his schlocky novel attracted minimal reviews, the rights were acquired by Avco Embassy Pictures in 1969, before being sold on to 20th Century Fox.

Irwin Allen’s Kent Productions remained signed to make the film. Allen and London-born director Ronald Neame hired a star-studded cast that included five Oscar winners: Hackman, Borgnine, Albertson, Shelley Winters and Red Buttons. They were, though, rejected by singer Petula Clark, who turned down the role of Nonnie Parry because she thought the script was “tacky and daft”.

Wendell Mayes, who wrote the first screenplay, changing the catastrophe from Boxing Day to New Year’s Eve and removing a gratuitous rape scene in Gallico’s original story, was quoted in the book Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1960s as admitting: “I’ll tell you what was attractive about The Poseidon Adventure: the money I was offered. I knew that it was going to be a big, bad, popular motion picture. After a couple of rewrites, I asked Irwin to please relieve me of the job. He brought in Stirling Silliphant and he changed it enough that he got first credit.”

As the filming start date of 4 April 1972 neared, however, pre-production costs were spiralling and new 20th Century Fox president Gordon Stulberg threatened to pull the plug on the film. Allen went straight round to Los Angeles’s Hillcrest Country Club, in the Cheviot Hills, and asked his wealthy friends Sherrill Corwin and Steve Broidy to back him with $4 million of their own cash, to assuage Stulber’s worries. They would be listed as executive producers.

“Oh Irwin, yes, we’ll guarantee you that money, but go away, we’re playing gin rummy, and that’s more important to us,” Neame recalled Broidy saying. “They got 50 per cent of the picture, and walked away with at least $20 million each, and they never even came near the studio,” added Neame. There were rumours that comedian Groucho Marx, also a pal of Allen, was another silent partner in funding, although that was never confirmed. Groucho visited the set and later attended the Christmas premiere party dressed as Santa Claus, joking that the film made him seasick.

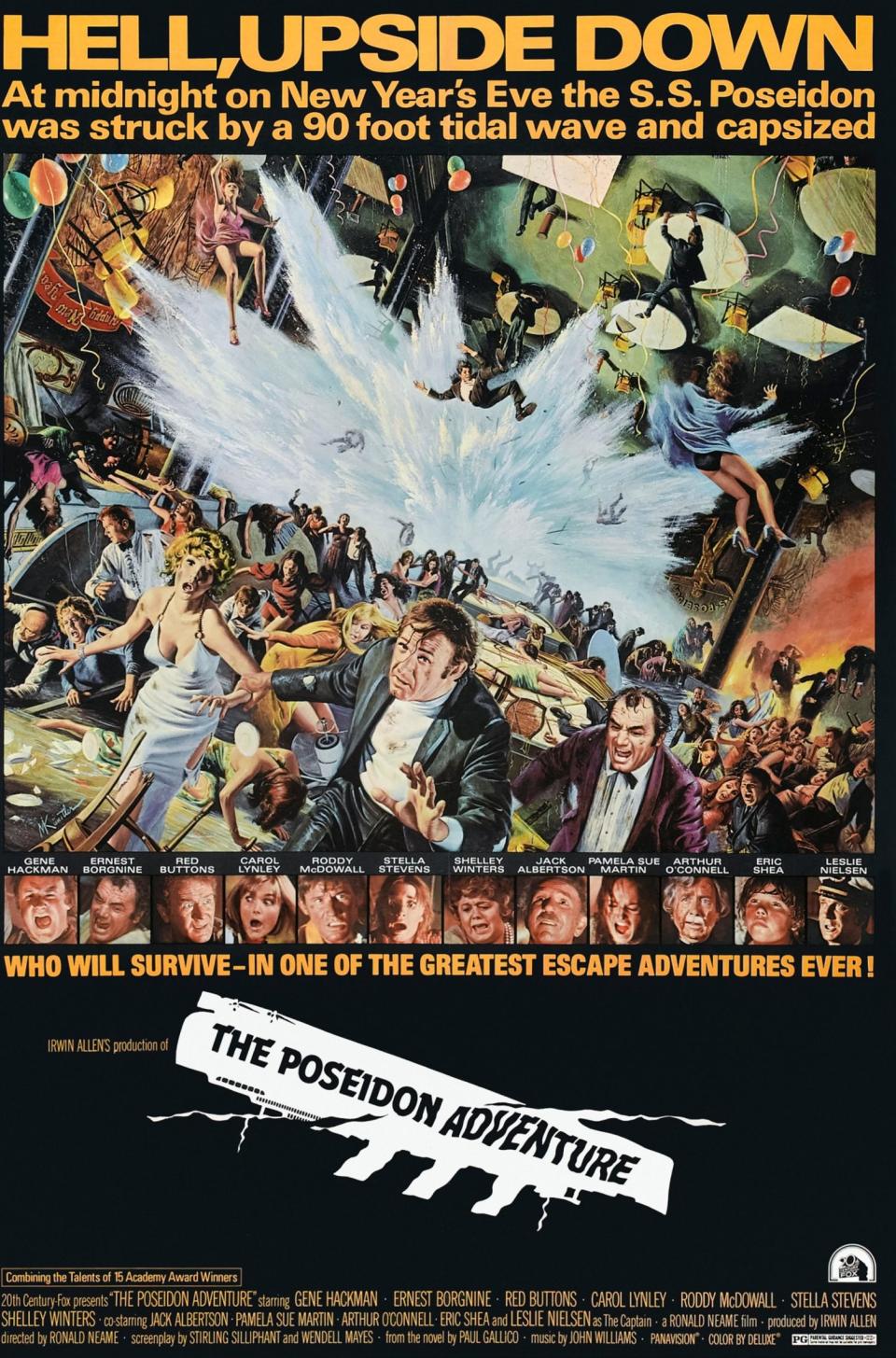

The 81-000 tonne SS Poseidon (“carrying 1,400 passengers and as high as an apartment building and as wide as a football field”) runs into trouble en route from New York to Athens. The iconic movie poster read: “Hell, Upside Down”, with the taglines, “At Midnight, on New Year’s Eve, the S.S. Poseidon was struck by a 90-foot tidal wave and capsized. WHO WILL SURVIVE – IN ONE OF THE GREATEST ESCAPE ADVENTURES EVER!”

Allen assembled a crew of 400 production staff and performers for one of the most technically complicated films ever made. “The actors have to go through what is, to put it mildly, hell,” said Neame in 1972. “They have to be at great heights, deal with fire, water, steam, they have to get dirtier and dirtier and get more and more bruised. The very physical problem of taking very important actors and actresses through a gruelling experience is the toughest film I have ever made. I told them that before the end of the film they were all going to hate my guts.”

The disaster is signalled when Captain Harrison, played by comic great Leslie Nielson, spots a giant incoming rogue wave through his binoculars. “It’s not going to be a bucket of water thrown in your face, they used a big wall of water for Poseidon. When the water is coming in, I say ‘Oh, my God’. It was an ad-libbed line,” he recalled. “We took the mickey out of it in a later Naked Gun movie.” Nielson’s frozen face scene is one of dozens of memorable moments, including the gigantic Christmas tree survivors climb to escape the upside-down ballroom.

Winters took her preparation seriously. The actress, who was 52 when she played a pensioner-grandmother, gained stacks of weight for the role, prompting Hackman to quip “She put on 40 pounds and had a lot of fun doing it”. In 1973, New York Post columnist Earl Wilson reported that Weight Watchers gave Winters a special achievement award for losing the “52 pounds” she put on for the role of Belle Rosen. Winters also learned how to hold her breath under water for about four minutes. “One of Jacques Cousteau’s scooba guys taught me how to do it,” she explained, “and I was a very good swimmer anyway. Johnny Weissmuller [Olympic champion and star of Tarzan] taught me how to swim years ago in Brooklyn.”

It's hard to think of The Poseidon Adventure without recalling Belle’s touching farewell to her husband Manny as she prepares to dive down and save Hackman’s character, Reverend Frank Scott, when he is trapped under water. The two stars did not get on during filming. “Gene would try to break my concentration. He’d say, ‘Just rub your nose if you are in trouble’,” she recalled. After that key scene, Hackman yelled, “you f_____, you were trying to drown me”. “I couldn’t deny it,” Winters later told interviewer Conan O’Brien, “and we didn’t talk to each other for 20 years after the film… he’s a great actor but he’s an a---hole.” Hackman later joked that “it took three days to film the scene where Shelley Winters dives down and saves me. She was the only woman I have ever worked with who could argue with you under water.”

This was far from the only tension among the huge ensemble cast. Carol Lynley, who ended up playing Nonnie, told film critic Roger Ebert that she had “defended Shelley a lot to everyone who hated her”. When Ebert replied “really?”, Lynley added: “She can be so selfish. Shelley can drive others to almost punch her in the nose.” Winter’s gambling losses were also a factor. “We used to get on each other’s nerves,” admitted Borgnine. “Shelley spent her break playing cards. She lost about 260,000 dollars to Jack Albertson, which she never paid.”

In 2012, talking to Smashing Interviews Magazine, Borgnine was asked to elaborate about co-starring with Winters. “She was a first-class b----,” he said. Borgnine also gave a damning opinion about Hackman. “Gene Hackman had just won the Academy Award for The French Connection. Apparently in that film, they just made up the lines as they went along, you know? We were given scripts for The Poseidon Adventure, but evidently he didn’t look at his script. He thought he was still doing French Connection. We had a rehearsal, and it came Gene’s time to speak, and there was nothing coming from him. He turned to me and asked, ‘Are we supposed to know these lines?’ I answered, ‘That’s the general idea’. That’s the last time I ever spoke to him. Don’t get me wrong, he’s a really wonderful guy.”

The battle for pecking order on the film was intense. Mort Künstler, who designed the iconic movie poster, said that in his drawings he was instructed to make the size of the person correspond to their contract value. “Gene Hackman had to be the biggest head and then Ernest Borgnine and then the sexy image of Stella Stevens as Linda Rogo. I had to measure the heads with callipers,” Künstler said.

There was even conflict between the director and producer. Neame later complained to FilmTalk magazine that “The Poseidon Adventure is an Irwin Allen production, which is fine. I don’t object to that. But it was supposed to be a Ronald Neame film, immediately after the title, and Irwin had my name put down after the cast. Whenever he did second unit work, he always made sure a camera crew was there, photographing him, filming him. He gave the impression that he did everything. That was so unfair.” Allen was described by Stevens as “the cheapest man in the world”.

Perhaps the most toxic relationship on set was between Lynley and the late comedian Red Buttons, who played James Martin, a role initially given to Gene Wilder. Lynley believed that Buttons was hostile because “he thought I had a better part than he did”. At a New York black tie promotional event to promote the film, a nervous studio press agent asked Lynley to ease up after she publicly described Buttons as “a horrible human being”.

Instead, according to Earl Wilson’s 1974 book Show Business Laid Bare, she laid into her co-star again, remarking: “Buttons was really sh___y to me, but he would cover it up. He steals scenes, steps on lines, tries to unsettle me. When we were about to do a scene, he would say, ‘Gee, Carol, I hope you can do this one, baby, don’t be nervous.’ He said everything sh___y to me that a man can say. I don’t like him, and he knows it. He is not very good. He is not a funny man… the best word for him is he’s a c___.”

The strenuous working conditions added to everyone’s stress. The 70 days of shooting were done in sequence, so the actors became progressively more tired and bruised. “It is still number one as the most physically exhausting movie I have ever done,” said Hackman, who headed straight for a holiday in Hawaii when the movie was completed. “By the time filming was completed, we were the dirtiest, sorest muscled, most bedraggled cast in movie history.”

“It was the most physically demanding role you can possibly imagine,” said Lynley. “We had to swim underwater, climb across tiny catwalks, walk over flames… and they kept us wet all day long. They hosed us down at least 20 times a day. And there were no safety precautions for the first two weeks of shooting. I’d be up there on a catwalk, and if I slipped, it was six stories straight down through flames to a concrete floor.”

Pamela Sue Martin, who portrayed Susan Shelby, remembers being so exhausted that she would fall asleep on stunt mattresses in-between scenes. “It was arduous even for an 18-year-old. I can’t imagine what it was like for the older members,” she said. “We did swimming and climbing and running through fire. It was pretty real; it wasn’t special effects. We were really uncomfortable, wet and dirty.” Although there were 49 stunt men and women listed in the credits, Lynley said that Neame insisted on showing the real faces of the actors. “When we look scared, it’s real,” she added

One stunt went down in Hollywood lore: the moment, after the ship has fully rolled over, when a character called Terry is hanging on for dear life to the bolted down table that is upside down and what is now the ceiling. Actor Ernie Orsatti was asked by Allen to make the 32-foot fall that ends with him crashing into the ballroom skylight. “You want me to do that fall? I’m not a stuntman,” he recalled telling Allen. In an interview for Stage and Screen, Orsatti recalled that Hackman and Borgnine were due to be off on the day of the stunt but turned up to watch, with Hackman bringing a camera along. “I asked Gene what he was doing there, and he smiled and said, ‘We’ve all come to watch you die.’”

Stunt co-ordinator Paul Stader told Orsatti, “do not lean your head back, you’ll break your neck. Pick a point, look at it and let go,’” Orsatti had to cling on to the table for six minutes before his fall and remembers jumping with his hands out before being “knocked colder than a cucumber”. The filmmakers got the shot in one take and Orsatti, who was due $100 for two spoken lines, was given another $250 for the fall. He suffered 16 cuts from the glass. “They wanted me to register terror, and they surely must have gotten it,” he added. “I was scared to death.” Orsatti went on to become a renowned stunt man and he became a huge draw at the annual conference of The Poseidon Adventure fans.

Allen, Neame and art director Bill Creber held daily production meetings to discuss the problems of each day’s shooting. In a promotional film about the making of the movie, Allen asked stunt co-ordinator Paul Stader to confirm that “no one is in danger, right? Not one chance in 10 million?” Stader, who was the stunt double for Hackman (his wife Marilyn was Winter’s double) assured him that everything had been worked out meticulously.

Perhaps the riskiest shot in the whole movie was when stuntman Larry Holt, doubling for Roddy McDowall’s character Acres, falls 40 feet through a vent shaft fall, with only minimal clearance from the concrete walls. He was caught by a net concealed by the churning waters in the tank. Despite being carefully planned, with multiple sketches, it was still a perilous manoeuvre. “I’ve had long experience in the action genre; this was the most dangerous stunt I’d ever seen,” said Allen, who paid Holt $1,000 for his work. McDowall said it was “the scariest” moment on set he’d ever witnessed.

The stunts were just one example of a remarkable attention to detail, and are one of the reasons that Creber described The Poseidon Adventure as a dream movie, because “the opportunity to have this sort of film comes along once in a career”. Costume designer Paul Zastupnevich, who earned one of the film’s eight Oscar nominations, spent time on cruisers doing his research. “I decided the only way I could do this correctly was to take a sea voyage myself. It was there that I got a great many of my ideas of what costumes people would wear,” he said.

The music was also top-class, including the Oscar-winning theme song The Morning After, and the Oscar-nominated score by John Williams. The quest for excellence extended to the fictional ship band, who were made up of leading California session musicians such as Robert ‘Waddy’ Wachtel, a guitarist who played regularly with Linda Ronstadt, Randy Newman and The Rolling Stones.

Some of the scenes were filmed on the real Queen Mary, which had begun a retirement docked in Los Angeles, and the interior sets at Fox Studio were constructed from the ship’s original blueprints. The carefully choreographed stunts and explosions were real. The dining room was tilted using hydraulic lifts and Creber and his team used more than 4,000 drawings and storyboards in planning the sets, special effects, construction and camera angles. They used a 22.5-foot-long miniature, built from a model of Queen Mary, for the outside scenes, and the spectacle of the flipping of Poseidon itself was one of the reasons the film won the Oscar for Best Visual Effects. This was a master class in special effects long before CGI.

The movie divided opinion. Red Buttons thought it was “simply the best disaster movie ever made” while Ebert described The Poseidon Adventure as “the kind of movie you know is going to be awful, and yet somehow you gotta see it, right?” Film critic Bernard Drew dismissed it for simply “capturing every cliché ever attempted”. No?l Coward wrote to Gallico to remind him of the strength of his story. “I was riveted by Poseidon from beginning to end. I didn’t actually read it hanging upside down from a glass chandelier, but I was certainly hanging from the chandelier for several days after”.

Although elements of the film now seem dated (women tearing off their dresses and blouses “for safety”), its success kick-started the Seventies obsession with disaster movies. ABC paid a record $1 million for the television rights and lots of people, including Neame, made fortunes.

Neame, who produced Brief Encounter, Great Expectations and Oliver Twist for David Lean in the 1940s, said that he went directly to England after its release to start working on The Odessa File. He recalled getting an urgent international call from Fox boss Stulberg. “He said, ‘Ronnie, I don’t care about the critics. The picture is going to make millions and millions.’ And it did; at the cost of $5 million, it grossed about $200 million. The Poseidon Adventure is not my favourite film. I thought that it would come and go in a few months. But on the other hand, it is my favourite film because it made more money than all the rest of my films put together—and a lot more on top of that.”

Hackman made his own fortune from the film, too, earning a straight fee of $1 million and much more besides from his contractual share in the gross takings. Just don’t ask him to sign any 50th anniversary memorabilia.