The Doors’ John Densmore: ‘Kids today wish they lived in the 1960s – but there was a dark side’

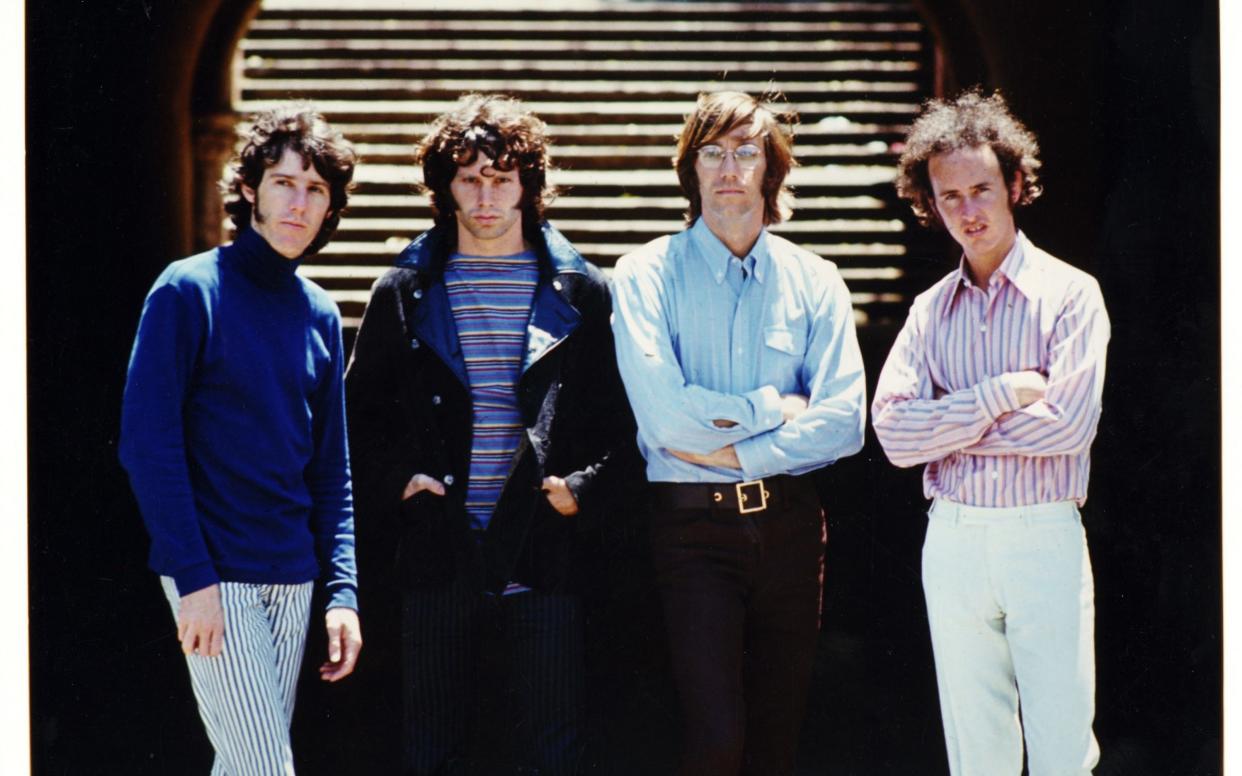

Sometime in late 1965, the four members of a newly formed band named The Doors – Jim Morrison, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore and Robby Krieger – sat down during a rehearsal in the garage at Kriegers’ parents’ house, and made a pact.

In a covenant of brotherhood forged in the idealism of the day, all four agreed that every decision to do with the group should be a consensus, that everything including songwriting credits should be shared four ways, and that each person had the power of veto on every decision.

Well, it was the Sixties.

Some 37 years, and innumerable gold and platinum albums, later, with Jim Morrison long in his grave, Densmore, the group’s drummer, faced the other two surviving members, keyboard player Manzarek and the guitarist Krieger across a Los Angeles courtroom, embroiled in a bitter dispute over – you guessed it – money.

Densmore had brought a case against his former bandmates to prevent them from exploiting the name of the Doors for tours or any commercial activities. In turn, he was being countersued by Manzarek and Krieger for $40m damages for persistently vetoing the use of the band’s songs for commercial purposes – a practice, Densmore claimed, that Morrison had always vehemently opposed.

“I can’t tell you the pain…” Even at a distance of 6,000 miles, talking on Zoom from his Los Angeles home, the anguish in Densmore’s voice is palpable.

“My musical brothers, and I’m suing them? Oh my God! But Jim’s spirit was with me. I just kept thinking about him and I had to stop this thing of the Doors without Jim. It’s the Stones without Mick. The Police without Sting. They could have called themselves ‘founding members’, ‘former members’, great man! But not ‘The Doors.’”

Densmore is 78, with long, thinning grey hair, a wispy beard, a tuft of a goatee beard and a laconic way of talking. That court case took place in 2004, but he has now published a book The Doors Unhinged, recounting the events leading up to the trial, and invoking the spirit of the Doors as not so much a rock band as a spiritual mission, and his desire to protect the legacy of the group and in particular Jim Morrison.

Densmore harbours no illusions about the Sixties being a halcyon period of light and love. “These kids who say, ‘I wish I’d lived in your era’ – there’s a dark underbelly, the Vietnam war, drugs, people dying.” And The Doors were its musical embodiment.

“Maybe that’s why the music has lasted because we reflected a fuller picture of the period.” It’s no coincidence, he says, that Francis Ford Coppola used The Doors’ brooding, ominous song The End for the opening sequence of his film Apocalypse Now. “We were the most popular group with the soldiers in Vietnam.

“Light My Fire was very joyous, and The End was the antithesis. We’d play Light My Fire as our last song live, and everybody was up dancing, and then they wanted an encore and we’d go out and play The End, and people would file out quietly like they’d been bludgeoned or something. Ray and I talked about how maybe them going home chewing on what they heard, rather than dissipating it in applause was better.”

With the looks of a Greek god, Morrison was the very personification of the idea of the tortured artist bent on hedonistic excess and self-destruction, the trajectory of his short and troubled career vividly illustrated in the 1973 book Rock Dreams by the writer Nik Cohn and the Belgian artist Guy Peellaert.

This depicted Morrison in two surrealist portraits, one perched on a stool in a gay bar, “a marvellous boy in black leathers, made up by two queers on the phone”, as Cohn wrote, and later, as a bloated, bearded figure slumped in the Paris bathroom where in 1971 he was found dead from heart failure, “full speed ahead on the American route to romantic martyrdom.”

“Well, some creative people have the Dionysian and the Apollonian together,” Densmore says. “Jim was crazy, but so talented. He had creativity and self-destruction built in. I loved him for his creativity, but I was a wreck seeing him turn into an alcoholic. I tried to warn him, but you can talk to somebody over and over, but until they internally switch, they’re not going to switch.”

The last word he would choose to describe Morrison, he says, is materialistic. “He was altruistic. When we got our first giant concert, mass adulation, Jim said, ‘Ok that was great, we had our first riot, let’s all go to an island and start over.’ He wasn’t into the more, more, more syndrome, like most of us are.

“We were all going crazy, buying cars and houses and he lived in a motel. He didn’t care about any of that stuff.”

In 1967, with the group’s debut album and the single Light My Fire certified gold, the group were approached with an offer of $75,000 to use the song in a commercial for Buick cars. With Morrison away in London, Densmore, Manzarek and Krieger agreed to the offer. According to Densmore, on his return to America, Morrison exploded, accusing his bandmates of making “a pact with the Devil.” The deal was cancelled.

By 1971, Morrison’s drinking, and the lingering controversy surrounding his conviction for profanity and indecent exposure during a concert in Miami, were taking their toll, and he fled to Paris. According to Densmore, he left an instruction with the group’s manager that no commercial deals should be agreed on his behalf. It was almost, Densmore says, as if he had a premonition of his death.

“I don’t think he wanted it or believed it, if that makes sense. But it was true.”

On July 3, 1971 Morrison was found in the bathtub of his rented apartment in Paris. The official cause of death was given as heart failure, although there was no autopsy. The remaining members of the group struggled on, recording two albums, Other Voices and Full Circle. With nobody, as Densmore puts it, who could “fill Jim’s leather pants”, Krieger and Manzarek shared vocals on the albums.

“I had big fights about that, but Ray said, we are the Doors, and I folded,” Densmore admits. And so, soon afterwards, did the group.

Densmore and Krieger went on to record as the Butts Band, while Manzarek recorded a succession of solo albums. But while the Doors no longer existed as a performing entity, their name continued to exist as a commercial one.

In 2002, the band received an offer from Cadillac of $15m for the use of Break On Through (to the Other Side) in a commercial for luxury SUVs. Krieger, he says, was “on the fence” about the offer. Manzarek was gung-ho about accepting it. But Densmore exercised his right of veto to reject it. (Cadillac used a Led Zeppelin song Rock and Roll instead).

“Jim was the soul of the band,” he says. “My thought was, he really cared about our catalogue, all our stuff, and he’s passed, he’s my ancestor, I’m going to honour that.”

The following year, relations between Densmore and his two former bandmates reached breaking point when Densmore was eased aside and Manzarek and Krieger recruited Ian Astbury, the singer from the British band the Cult, and Stewart Copeland, the Police drummer, and began touring under the name The Doors of the 21st Century – using the group’s famous logo, and with the words ‘of the 21st Century’ printed in very small letters on the advertisements and tour posters.

Densmore sued Manzarek and Krieger over their unauthorised use of the band’s name, logo, and images. Manzarek and Krieger promptly countersued, alleging that “the legendary performing group the Doors is currently being held hostage by the arbitrary, capricious and bad faith actions of its drummer” and seeking $40 million in damages.

“We used to be a collective body intent on making art, not a bunch of individuals mainly out for ourselves or the money,” Densmore writes in The Doors Unhinged. “Those were the good old days. Now the remaining Doors [were] ready to tear asunder everything we stood for in the beginning.”

Densmore originally wrote The Doors Unhinged in 2013, publishing the book himself. But the book – now published with a new preface and afterword – has acquired a particular topicality in recent times, he says, with an increasing number of what might be described as ‘heritage’ artists cashing in on their song publishing or recording rights for astronomical sums.

In 2020 Bob Dylan sold his catalogue of more than 600 songs to Universal Music for a reported $300m. Dylan, being Dylan, has always held up one finger to high-mindedness; in 1994 he allowed the accounting firm of Coopers and Lybrand to use Richie Havens’s rendition of The Times They Are A-Changin’, and he has lent his name to advertising for Victoria’s Secret and the whiskey brand Heaven’s Door.

In 2021 Bruce Springsteen sold the master recordings and publishing rights for his music to Sony Entertainment for a record reported sum of $500m.

“Holy moly!” Densmore whistles through his teeth. “No judgement. It’s a free country, do what you want with your money.

“I’m Mr PC over here. People either think I have integrity, or that I’m nuts, I don’t know which. However, I would say to a new band, if you have to sell your songs to a commercial to pay the rent, do it. It’s hard out there.”

Paying the rent was never a problem for the Doors. Over the years, the group have sold more than 100m records worldwide, making them one of the best-selling bands of all time.

“But maybe money’s an addiction... In the book, I have a picture of me in a little sports car, and under it, I wrote ‘Just a little more and I’ll be happy.’ More, more, right?” He laughs.

In the 1980s, he says, he began tithing ten per cent of his income to environmental organisations like Rainforest Action Network and the Sierra Club.

When Oliver Stone made his film The Doors in 1991 – paying handsomely for the use of the group’s music – Densmore says, “I looked down at my hand signing those tithing cheques and it was shaking. It was the hand of greed, right there in me! But if I’m nervous about writing these big cheques to charity it must mean I’m doing really good, so what’s my problem? But money really is like heroin.”

In The Doors Unhinged the trial, and in particular what he describes as Manzarek’s “salesman mentality”, becomes a metaphor for Densmore’s wider reproach of corporate greed and the corruption of Sixties idealism. Manzarek, he writes, was “my nemesis” but also “my teacher”.

“Maybe I should dedicate this book to him,” he writes, “since he has helped me define myself, my morals and has forced me to draw the line in this consumer-obsessed society in which we live.”

Testifying during the trial on the question of the vetoed Cadillac deal, Manzarek suggested that the claim that each member of the group had the power of veto was merely “part of the Doors mythology”, and “a fiction’’. Had Morrison lived, Manzarez maintained, he would have outgrown his anti-establishment stance of the Sixties, “seen the writing on the wall” and accepted the Cadillac offer.

At one point, the trial descended into the surreal with Manzarek’s lawyer attacking Densmore’s “communist” beliefs, and implying that he was “a supporter of Al Qaeda” citing Manzarek as saying that Densmore had described 9-11 as “a wake-up call” for America.

“They had no case,” Densmore says. “So what do you do? Character assassination. The lies and tripe that were coming out made me crazy. If the case was going on today I’d probably be accused of being a supporter of Hamas.”

After a trial lasting four months, the jury decided in Densmore’s favour, and Manzarek and Krieger were forbidden from performing under any name that included The Doors, without Densmore’s permission. The counter-suit against him was dismissed. He was awarded a quarter of the profits from The Doors of the 21st Century tour while his former bandmates continued to perform as Manzarek-Krieger.

Densmore and Manzerak would not speak again until 2013, when Manzarek was dying from cancer in Germany. Learning he was ill, Densmore called him. “I was so grateful that he picked up the phone – I mean, none of us pick up the phone nowadays, am I right? We didn’t talk about the case, but there was still that friction between us. We talked about Ray’s health, and I said to give his wife Dorothy my love. It was just a short conversation – and I didn’t know it would be the last one.”

When Manzarek died, he called Krieger. “Robby was my best friend. We’d had a deep, long life together, making great music. How could I not love him?

“I said, death trumps everything, Robby. Let’s get together and play some music together.”

Later that year, they performed at a charity event at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Just the two of us, 3 or 400 people in the audience. And we said, ‘We’re not very good singers, will you help us?’ And all of them sang every song as we played.”

He shakes his head. “Such healing…” The first song they played, he says, was People Are Strange.

The paperback of The Doors: Unhinged: Jim Morrison’s Legacy Goes On Trial (paperback)