Drugged, raped, fired: How flight attendants' claims are fueling a #MeToo movement in the airline industry

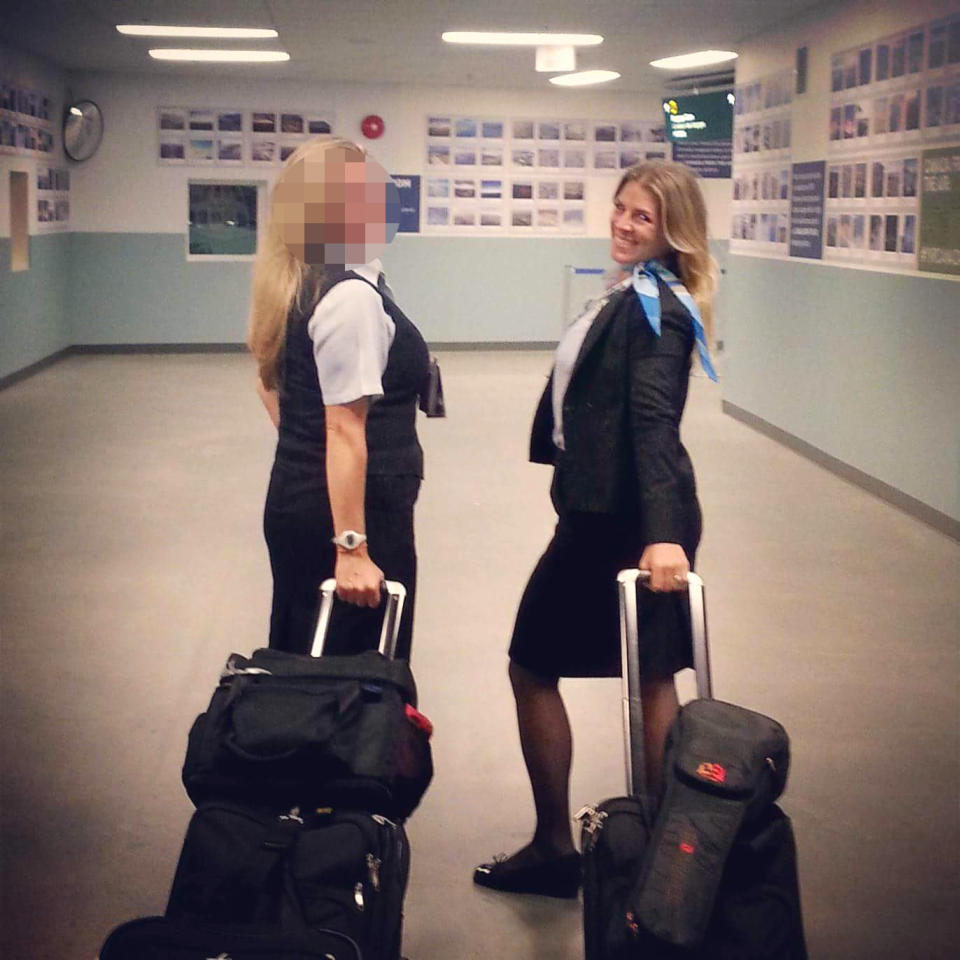

When I was a 25-year-old flight attendant, I was sexually assaulted by a male pilot. I was in Maui, on a layover, working for the Canadian airline WestJet, when, following a typical post-shift gathering for drinks in the pilot’s hotel room, he attacked me repeatedly and attempted to rape me.

Somehow, through sheer adrenaline-fueled strength, I was able to escape.

I reported the incident to my company, the police, and my family — an embarrassing process that helped me understand right away why so many women don’t report their own assaults. But the experience turned me into a pre-#MeToo movement advocate who has made it her mission to break the silence around sexual harassment in the airline industry, and to help those who have been assaulted bring their attackers to justice.

Just like in the entertainment industry, I have since learned, the cover-up of rape and sexual assault by powerful airline corporations has a long, dark history. It’s rooted in the fact that the industry has historically profited from the sexualization and dehumanization of female flight attendants, for whom, up until the ’70s, the courts deemed “female sex appeal” to be a “bona fide occupational qualification.”

Airlines are not oblivious to the harassment of flight attendants and have recently become focused on flight attendant harassment by passengers, often with the vocal support of politicians — a vital effort, as a recent FBI report found that sexual assaults on commercial airline flights are on the rise, from 38 in 2014 to 63 in 2017. (The actual figures could be higher, because sexual assaults are generally underreported.)

Still, some ugly facts remain when it comes to the dynamics between pilots and flight attendants — not the least of which is the fact that 93 percent of pilots in the U.S. are men and 79 percent of flight attendants are women, which speaks to an inherently gendered power imbalance. Plenty of recent anecdotal reports point to the high degree of harassment this imbalance fosters. Further, a recent survey by the Association of Flight Attendants union found some disturbing claims — with nearly one in five flight attendants saying they’ve been sexually assaulted, and 70 percent saying they’ve been sexually harassed in the air.

Spirit, Alaska Airlines and United Airlines have started working with the union to end the harassment, but the focus, again, is on in-flight harassment by passengers. What about when it’s a co-worker doing the grabbing? That’s been the case, over and over again, in the many incidents that have pushed flight attendants to come forward — including me with my own story.

Trying to find justice

At the time of my own assault, in my naiveté, I believed the company would do the right thing when I reported the attack. Instead, WestJet responded by handing me a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) — which I refused to sign — and told me that because it was my word against his, and that he hadn’t been charged, there was nothing the company could do. (I had certainly tried to press charges, but the Canadian police informed me that, due to the technicality of no penetration having taken place, I had no just cause).

The company explained that if I brought up the pilot’s name publicly, I’d be subject to disciplinary action, even termination, and that the NDA offer was for my own sake. Further, management told me that if WestJet disciplined him, he could then turn around and sue the company.

Then, in the only immediate action it took to relieve my concerns about the situation, the airline began monitoring my work schedule so that I wouldn’t cross paths with the pilot who assaulted me. It eventually suspended the pilot’s qualification (called ETOPS) for flying over a large body of water.

Still, in 2015, I found the courage to begin talking about sexual harassment statistics during a crew resource management training class, a mandatory annual session during which pilots and flight attendants discuss safety issues. Speaking up like that was not the norm, and you could hear a pin drop in the room when I did. Still, my statement was quickly met with a hand in the face by the pilot in charge of the class, who told me I was being sexist for stating that more women had been harassed than men.

More women come forward

But it eventually brought me lots of support from other women, which encouraged me to keep going. So in April of 2016, I publicly filed a lawsuit against WestJet for negligence in how they dealt with my complaint. I gave my first of what would be many on-camera interviews with the Canadian outlet CBC National, hoping it would reach as many women as possible. I was terrified, but it worked.

Within hours of the story airing, half a dozen women came forward from WestJet with similar claims — of being chased around hotel rooms, assaulted on cross-border layovers, ruthlessly re-victimized, and being forced to stay quiet after reporting the incidents. The story became national, and then international, news. The Globe & Mail, HuffPost, and Vice News all picked up the story. I and my lawyers were shocked at the positive response. I had been preparing for the worst — slut shaming, vilifying — and of course I did receive some hate mail, mostly from WestJet employees. But WestJet’s response to the claim was to deny it.

In response to my allegations for this article, a spokesperson from WestJet tells Yahoo Lifestyle: “Safety in the workplace is a matter we take most seriously and WestJet remains committed to ensuring that we provide a safe and harassment-free work environment for our employees and guests. As this matter remains before the courts, we will not be providing further comment.”

Today, I continue to fight for justice for flight attendants and other women in the airline industry who say they have faced sexual assault — women like Betty Pina, a veteran who sued Alaska Airlines claiming it failed to hold a pilot accountable after he allegedly drugged and raped her, and women like Ashley Geffre, who also sued Alaska Airlines. A former flight attendant for that company (2014 to 2017), she contacted me last year, after publicly sharing her story about being drugged by a male pilot while on a layover in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Ashley reported the assault to both the airline and her union, the Association of Flight Attendants Alaska, but instead of being offered support and guidance, she says she was fired.

After filing her complaint, Ashley attended a daylong meeting — in a room with the man she was accusing of rape — that was orchestrated by her employer through its requirement of forced arbitration; that arbitration never happened, because a group I led protested. But for many women, a company’s typical response to sexual harassment complaints is forced arbitration: That’s when a company requires employees to deal with a dispute themselves, with victims waiving their right to sue, and both parties agreeing on a solution, through the company’s chosen arbitrator.

Alaska Airlines disputes some of Ashley’s story in a statement provided to Yahoo Lifestyle: “When situations arise that are inconsistent with the values of Alaska, we investigate them fully and act in accordance with our policies. We do not comment on personnel issues. We have a labor contract with our flight attendants. If a represented employee is dismissed from the company, that employee has the right to request a grievance arbitration hearing. A grievance arbitration hearing is not an example of forced arbitration.”

Forced arbitration is a standard part of airline employee contracts, and it robs employees of the power to seek recourse through the courts. And, because it ultimately works as a silencing tool, some politicians have made it their mission to end sexual misconduct forced arbitration, through legislation introduced in both the House and the Senate and known as the “Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Harassment Act of 2017.”

But the fight continues. That’s why Ashley and I have joined forces with some other former and current flight attendants to create You, Crew and #MeToo, an online support website specifically for airline workers. And it’s why I am leading a proposed class-action lawsuit against WestJet claiming a systemic breach of contract for failing to protect their female flight attendants — a suit that is the first of its kind in the province of British Columbia. If we win, we will set a precedent for all women across the Canadian work sector.

The stories, meanwhile, don’t stop coming. As recently as last month I received messages from women across Canada who found my story and reached out to me in desperation.

If you are a survivor of sexual violence in the airline industry, you can know one thing for certain: You are not alone. So please, tell someone, anyone. Tell me. Stand up to your airline for failing to provide a safe workplace for all women. Be insubordinate. Don’t sign an NDA — and if you have, try to find legal aid in breaking it. Go public. Come forward. Join our fight, even quietly — like the female WestJet pilot who came up and hugged me during a Vancouver International Airport protest. She whispered in my ear, “You know you have a secret army, right?” before briskly walking away.

Because our moment is now. And #TimesUp for the airline industry.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Christine Blasey Ford is still getting death threats: What’s the long-term fallout for survivors?

When sexual harassment becomes dinner conversation: a #MeToo holiday survival guide

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.