Can I Dry Age Beef At Home? | The Food Lab

Many paper towels, meat weigh-ins, and blind taste tests later, we've decided what's myth/what's fact when it comes to the DYI dry aging of individual steaks.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

Have you ever wondered why the steak at a great steakhouse can taste so much better and more tender than the steaks you pull off your backyard grill? Or why they cost so much more?

Two little words: dry aging.

Dry aging is the process by which large cuts of beef are aged for anywhere from several weeks to several months before being trimmed and cut into steaks. It's a process that not only helps the steak develop flavor, but also makes it far more tender than it would be completely fresh.

Because of the large amounts of space and precise monitoring of temperature and humidity required for proper dry aging, it remains largely the realm of fancy steakhouses like Peter Luger, specialty meat purveyors like Pat LaFrieda, or the occasional high end supermarket like Whole Foods or Fairway.

But if there's one question I hear more often than any other about expensive beef, it's, "Can I dry age steak at home?"

Most experts agree that the prospect ranges from either impractical to outright impossible, but I'd heard from several reputable sources (including Cook's Illustrated and Alton Brown) that aging individual steaks is, in fact, possible in your home kitchen. Cook's Illustrated even went so far as to say, "You can skip shelling out extra money for commercially aged cow."

That's a pretty bold claim indeed, and one that has the potential to put a dent in the business of several very lucrative steakhouses and meat purveyors.

What Is Dry Aging? A Primer

Before we get into the testing, let's take a quick recap of what dry aging is all about. When beef is dry aged, there are three basic changes that occur to its structure:

Moisture loss is a major factor. A dry-aged piece of beef can lose up to around 30% of its initial volume in water loss, which concentrates its flavor. A great deal of this moisture loss occurs in the outer layers of the meat, some of which get so desiccated that they must be trimmed before cooking. Thus the larger the piece of meat you start with (and the lower the surface area to volume ratio), the better your yield will be.

Tenderization occurs when enzymes naturally present in the meat break down some of the tougher muscle fibers and connective tissues. A well-aged steak should be noticeably more tender than a fresh steak.

Flavor change is caused by numerous processes, including enzymatic and bacterial action. Properly dry-aged meat will develop deeply beefy, nutty, and almost cheese-like aromas.

Because so much of the meat's weight is lost due to moisture loss and trimming, and because of the massive storage space required for aging beef, dry-aged beef comes at a significant premium cost. Commercial dry aging facilities will age their beef anywhere from three weeks up to four months, depending on the needs of the client and the costs people are willing to pay.

This process is strikingly different from the method recommended by both Cook's Illustrated and Alton Brown, both of whom recommend wrapping individual steaks in cheesecloth (Cook's recommendation) or paper towels (Brown's recommendation) and storing them on a rack in the fridge for four days before cooking them.

Four days for the home version versus a minimum of three weeks for the real stuff is a pretty striking difference in time. But could there be something I was missing?

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

I called up Mark Pastore, president of Pat LaFrieda Meat Purveyors—the man in charge of their New Jersey aging facility that at any given moment is aging up to a half million dollars' worth of meat*—and asked him what he thought about the four-day-age.

*You can catch a video of the action here.

"Wrong, wrong, wrong," was his unhesitant reply. "I'm not sure where to start. First of all, you're not going to taste any difference after four days. For dry-aged beef, you need to go 21 days at a bare minimum for any noticeable changes. The shortest we'll age anything is 30 days."

Josh Ozersky, organizer of the former Meatopia festival concurred, adding that for improving tenderness, two weeks is the minimum. "At that point, assuming you have a good dry aging room, the meat will have broken down a little. However it does not," he continued, "take on the 'funky' flavors associated with dry-aged beef." He went on to stress that a "good dry aging room" is a "very important qualification," reiterating the opinion among experts that meat cannot be aged at home.

Interesting. So what can be gathered here is that perhaps some of the enzyme-based tenderizing effects of dry aging can occur in as little as two weeks, but for real enzyme and/or bacteria-based flavor changes to occur, you need to age for longer. I'd always been under the impression that with rare exceptions (such as the so-called "wet aging," in which meat is stored in hermetically sealed Cryovac bags), tenderization and flavor development went hand-in-hand.

I spoke with Jeffrey Steingarten, food writer at Vogue magazine, and one of the early proponents of long-aged beef from back in the mid-'90s when only a handful of steakhouses in the country were serving beef aged for longer than two weeks. "I called up 100 of the best steakhouses in the country, and only three were using prime beef and aging it longer than two weeks." Three in the whole country! "The old literature says that there's no advantage to aging over two weeks," he says. "But that comes from a time when the quality of a steak was judged only on tenderness. Flavor wasn't an issue—in fact, some of the top steakhouse chefs at the time balked at the idea of serving four or six-week aged steaks. 'People won't like the flavor,' they said."

How wrong they turned out to be!

Going on, Steingarten says, "Maybe there isn't an increase in tenderness after two weeks—I haven't done the test to prove it—but if I'm looking for the flavor of aged beef, three weeks is definitely not enough. That's just what decent beef tastes like, it doesn't start taking on any aged flavor characteristics until well after that."

Pastore had another concern with home-aged meat. "Safety. Your home fridge is full of all kinds of bacteria that you don't want building up on your meat. There's too much humidity in the air, and not enough circulation. A dry aging room needs constant circulation to keep that bad bacteria from getting a foothold." Steingarten concurred, saying that good aging rooms keep their air moving at around five miles per hour at all times.

I contacted several editors and current employees at Cook's Illustrated magazine with questions on their own tests and conclusions, but they declined to comment on the issue.

I'm never one to just take people's words for it without some strong data to back up claims, but in this case, I've got a few of the foremost meat experts in the world telling me one thing, and two of the most respected sources for home cooking telling me the exact opposite. Who's right?

My only recourse? Examine the evidence, step into the kitchen, and get to the bottom of the mystery myself. That's exactly what I did.

The Experiment

To start my testing, I decided to follow the basic Cook's Illustrated/Alton Brown protocol: take fresh steaks, wrap them in several layers of cheesecloth or paper towels, place them on a rack in the back of the fridge, and let them sit for up to four days.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

For thoroughness' sake, I repeated the experiment a total of four times (twice with ribeye steaks, twice with tenderloin steaks) with six steaks in each batch aged for nine days, seven days, five days, two days, one day, and zero days.

I knew that in order for the taste test to be fair, the steaks would all have to come from the same steer, so I cut up a couple of boneless ribeye roasts that were donated by our friends at The Double R Ranch into identical steaks along with a couple of whole tenderloins purchased from my local Fairway butcher counter. But there was immediately a problem: How do you age some steaks and keep the others fresh?

The only way I know of keeping steaks fresh for a significant period of time is to freeze them, but this posed problems of its own.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

See, when meat freezes, the water inside its cells forms ice crystals. This is good news for halting any sort of organic changes in the meat—without water activity, most bacteria and enzymes are rendered completely inert—but it can also cause some of those cells to rupture, which can, in turn, cause juices to spill from the meat as it thaws. A frozen-then-thawed steak will naturally be slightly mushier and more prone to moisture loss than a previously unfrozen steak.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

I decided to compensate for this by carefully Cryovac-ing and freezing all of the steaks. Once frozen, they should remain completely inert until I defrost them. In this way, I made sure all of them were on a level playing field to start. As a control, I also included a freshly-bought, previously-unfrozen steak in my lineup on tasting day. It wouldn't be from the same steer, but it would at least give me a point of reference.

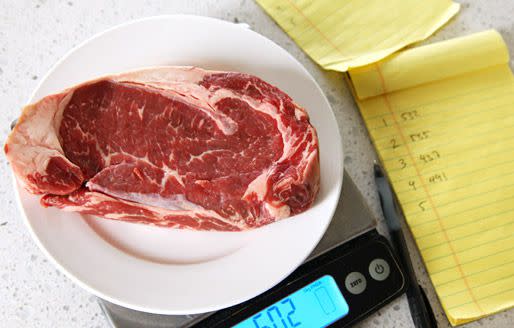

When you're lucky enough to have a job you love doing, the only real difference between messing around in the kitchen and doing real work is in the measuring, so I pulled out my scale, weighing every steak before I began the aging process. Every day, I'd pull out a new steak from the freezer, let it defrost in its Cryovac bag in water kept at 40°F (4°C), wrap it in either cheesecloth or paper towel (as the case may be, depending on the specific experiment number), and place it on a rack in the fridge.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

"What is this? A dry aging room for ants?" my wife said a few days later as she went in for the milk. Indeed, over the next several weeks, a collection of steaks at various stages of aging began to populate my fridge in waves. I spent my days thinking of ways I could slip the line, "You should check out the science experiment I found in my fridge the other day," into conversation.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

On the 9th day of each round of testing, I removed the steaks from the fridge, carefully unwrapped them, and weighed them again in order to ascertain degree of moisture loss.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

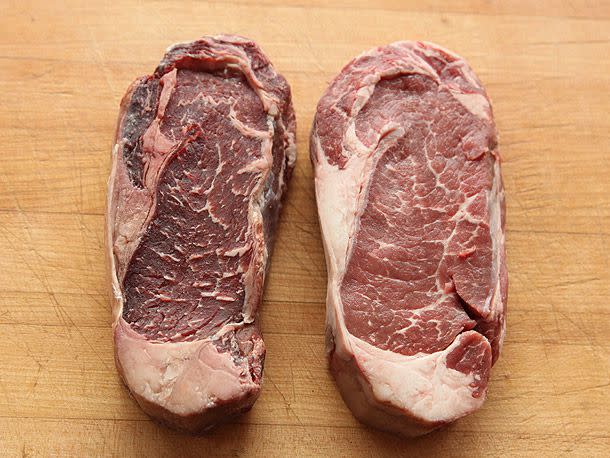

The oldest steaks clocked in at around 7% weight loss, while the day old steaks barely broke 3%. Far more noticeable was appearance. While the freshest steaks had creamy white fat and a bright, wet-looking wetness on their cut surfaces, the older the steaks got, the darker their color and the tighter their appearance became, an indication that indeed, water was leaving them, concentrating their flesh.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

Now, I'm not the kind of guy to accidentally overcook a steak. And I say this with no hint of arrogance or smugness (there are plenty of other things I am smug about, like my video game skills), but merely as someone who stopped overcooking their steaks way back when he bought his first Thermapen thermometer. Still, I'm not one to gamble on a couple weeks' worth of work lightly, so I decided to split all of my steaks in half before cooking, just in case.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

This ended up revealing a very fascinating cross-section:

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

The photo above is the cross-section of a fresh, unaged piece of beef. If you look very closely, you'll see that the very center has a distinct purplish cast to it, while the outer layers tend to be a darker, cherry red. This has to do with oxygen penetration and the conversion of myoglobin to its various forms.

In its native state, myoglobin forms a compound called deoxymyoglobin. This is the purplish color of freshly cut meat, before it's been exposed to any of our atmosphere. Let this purplish, cut surface sit in the presence of oxygen for long enough, and it'll turn into oxymyoglobin, that familiar red color we look for in fresh meat.***

***Falsely look for, I might add, as color is an indication of atmosphere, not freshness.

Now take a look at the cross-section of the aged steak:

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

You'll notice immediately that the purple core is significantly smaller, and it's soon followed by a brownish layer, and finally a dark, cherry-red layer on the exterior. What's going on here?

It's a matter of timing. The brown color is the color of metmyoglobin, the form that oxymyoglobin converts to after prolonged exposure to oxygen. In the case of this steak, oxidation has penetrated deep enough and far enough into the steak as to create a significant ring of deoxymyoglobin. Meanwhile, the very outer layers of the steak have taken on a deep, dark red color, an indication that moisture loss has led to an increase in density around the edges of the steak, and therefore an intensification in color.

What this also tells us is that in the timeframe we're talking—up to a week or more—small molecules do indeed penetrate deep into a steak. Is it possible that some of those molecules might be affecting flavor? And what about that dried out edge? How would that affect texture and flavor?

A quick gag-inducing sniff test proved the worst in the case of the nine-day aged steaks: They were all rotten. Even cutting into them revealed a core of edible meat only a few eighths of an inch thick. I threw them out, rather than risk the health of my tasters.

Browning Qualities

I cooked the remaining steaks in a large cast iron pan, using an infrared thermometer to ensure that the surface temperature of the pan was identical before placing the meat inside it.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

Normally, I'd cook my steaks by flipping them frequently in order to promote faster, more even cooking throughout the meat. In this case, however, I stuck to a single flip in the middle for the sake of easy repetition and accuracy.

My goal was to cook them all to 120°F / 49°C (right around medium-rare), but even before I started taking their temperature, I noticed one major difference in their cooking quality: The completely fresh steak showed reduced browning properties. Take a look at the steak on the right versus the one on the left below.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

This happens for two reasons. First, more moisture can cause it to buckle and bend when that moisture suddenly starts to leave (thanks to the heat of the pan), causing certain areas of the steak to shrink faster than others. Small perturbations in the surface of the meat are amplified.

Second, because those browning reactions (collectively known as the Maillard reaction) take place when proteins and sugars are heated to high temperatures—generally in excess of 300°F (149°C) or so. Meat contains a lot of water, which acts as a built-in temperature regulator, preventing the meat from getting too hot until it mostly evaporates. So for completely fresh meat to brown properly, this surface moisture must first be driven off. Meat that has spent time in the refrigerator, however, already has a dry surface, allowing it to brown more efficiently.

Slow browning is not the end of the world—just by letting the steak sit a few seconds longer on each side, I easily compensated for the discrepancies. Even more interestingly, the biggest difference in browning was between the non-aged steak and the one-day aged steak. After that, there wasn't much difference, no matter how long the steak was aged.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

Indeed, subsequent testing showed that even an overnight 8- to 12-hour rest on a rack in the fridge is sufficient to create a dry enough surface on the meat for optimized browning.

H. Alexander Talbot and Aki Kamozawa of the blog and book Ideas In Food cited similar results in an email to me. "We found air-dried makes a difference. Certainly much better browning. but no real funkiness. The tender issue is debatable. The drier exterior seemed to make the interior feel moister and more tender. But we did not taste blind in this case."

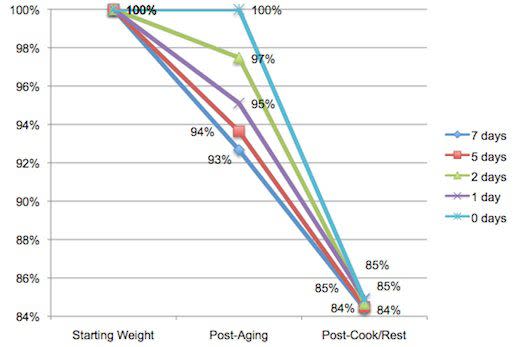

Other than browning, I noticed no major differences in the way the steaks cooked. The real surprise came after I weighed all of the steaks post-cooking to see how much moisture they lost from their original state.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

Well, would you look at that? Turns out that whether aged for seven days, zero days, or anything in between, once the steak is cooked to 120°F, the moisture loss levels are pretty much identical. What this means is that whatever moisture loss occurs in the very outer layers of the steak due to dehydration during aging would have been lost anyway during cooking.

It also indicates—even before tasting—that any arguments that rely on the concentration of meat flavors due to moisture loss are most likely bogus, since the final moisture loss is identical in all the steaks across the board.

How would they stack up in actual blind tastings?

The Taste Test

I performed two separate taste tests, using two separate groups of tasters to gather my results. The first taste test was a simple blind side-by-side ranking, in which I asked tasters to taste all the meat, give me notes on relative tenderness and flavor, and rank them in order of preference.

Results? Between the steaks aged for zero, one, two, and five days, there was no discernible pattern to their preferences. The one result that did show a definite trend was that the seven-day aged steak was consistently ranked at the bottom in terms of flavor, with tasters citing "old refrigerator" and "stale" flavors.

So there is indeed something to Mark Pastore's claim that meat will pick up the flavors present in a refrigerator.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

For the second round of taste tests, I went one step further, performing a triangle test, the standard test when rigorous results are needed for sensory-based studies. To perform the test, a subject is presented with three samples. Two of the samples are identical, while the third is different. The samples are presented together, but in random order (so one taster may get AAB, while another will get ABA, or BAA). The taster's only job is to determine which of the three samples is different from the other two. The test was given to 12 different tasters.

And guess what? For steaks aged five days or less, tasters could not identify which steak was aged and which was fresh. There was literally no detectable difference in the cooked steaks. In fact, out of the first seven tasters, none of them were able to correctly identify the odd-steak out. Even with completely random guessing, there's a 94% chance that at least one of those tasters should have gotten it right. In all, only two out of 12 tasters correctly identified the different steaks, a number still lower than you'd expect from pure chance alone. Again, steaks aged for seven days were ranked below the rest of the steaks for having stale flavors.

Finally, we tasted the fresh and five-day-aged steaks against steaks that were aged for 28 days in a professional aging cabinet. The difference was immediately, undeniably perceptible, with the true aged steaks offering a far more tender texture and a significantly deeper flavor. Frankly, I don't see how anyone could possibly confuse the two.

So there we have it. Some pretty darn strong evidence that the so-called "aging" of individual steaks in the refrigerator is entirely bogus.

Result Explanation

So why can't a steak develop good dry-aged flavor in the home kitchen? Again, the experts disagree. My personal theory, and one that is shared by a number of others, is that the flavor changes in dry-aged beef—those funky, nutty, cheesy aromas that develop—come largely from bacterial action on the surface of the meat. This makes sense to me, as those flavors are most powerful near the cut edges of a steak, or near the bones, whose porous structure makes it easier for bacteria to get a foothold. The remainder of an aging primal is either covered in a thick layer of fat, or is made of muscle, which dries out and forms a cuticle that becomes impenetrable to moisture or bacteria after the first couple weeks of aging. (As a result, an aging primal's moisture loss will slow to a crawl after this cuticle is formed.)

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

According to Pastore, the fauna that populates the surface of the meat and causes these flavor changes has to be abundant in the air to begin with for optimal effect, much like Spanish Jamón Serrano makers or Italian prosciutto producers say that aging a ham amongst other hams is essential for its flavor development. "You need to age meat with other meat so that their flavors can build together, not with cheese. In your fridge, you've got onions, cheese, vegetables, condiments. All that stuff that can give it off-flavors or worse, inoculate it with dangerous bacteria."

This certainly rings true with taste test results in which tasters complained of off-putting, "old butter"-like flavors in fridge-stored steaks.

Steingarten has another take, saying that he believes the flavor change to be largely enzymatic—that is, caused by chemical catalysts that are naturally present in the meat to begin with. This is a difficult theory to test without an irradiated piece of beef and the sterile environment of, say, a microchip manufacturing plant. Unfortunately we can't even keep the darn dogs out of Serious Eats World Headquarters, much less the microscopic bugs.

An even more important factor is the obvious: surface area to volume ratio. With a large primal cut of the type that is used for aging in a steakhouse or specialty meat purveyor, the amount of meat you actually lose to moisture loss or hyperactive bacteria is—at least ratio-wise—quite small. Even after trimming a good inch or two off the surface of a prime rib, you're still left with plenty of serve-able meat underneath.

With a single steak, or even a trimmed rib roast that you'd be able to find for home consumption, on the other hand, this ratio is exaggerated. With a 1 1/2-inch thick steak, you might lose over 50% to rid yourself of overly rotten bits if you were to attempt to age it for a very prolonged period of time. (Even after nine days, long before experts say aging offers any benefits, only a small sliver of edible meat was left in the center of a steak.)

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

Other Aging Options

We've still got a ton of unanswered questions here. What about so-called "wet aging"? Can you dry age meat that's lower in fat than Prime grade? How much effect does that fat have on dry aging? What about air quality? Would an inert environment help? Could we perhaps get Richard Branson to shoot a cow into space to test dry aging in a weightless vacuum? Or more practically, you may be asking, "Well, how come you don't just try and age a larger cut of beef in the fridge to mitigate these problems?"

Good question, and one that I answered later (because this post was already too long as-is). As I wrote this article I had an eight-pound, fat-on, prime rib roast aging in my refrigerator, and posted the results several weeks later. A few readers also mentioned the UMAi Drybag Steak system, a specially-made bag that purports to allow true dry aging at home by allowing moisture exchange, but preventing oxygen and other "bad" bacteria from getting into contact with your meat. I had a couple of steaks in the fridge resting in an UMAi Drybag as I typed this.

So what's the too-long/didn't-read summary here? Simple: Aging steak in the fridge is useful if you do it for a minimum of half a day, but only to aid in browning. Aging any longer than that will do nothing more than add a nice, stale-refrigerator aroma to your meat. If that's the kind of thing that floats your boat or butters your beef, then by all means, go right ahead.

Advice: You might have a friend who leaves their steak sitting wrapped in cheesecloth on a rack in their fridge for a few days. They may tell you, "I dry age my own beef." If you're lucky, they may even cook that meat for you, and it may well be delicious. Do not, I repeat DO NOT suggest they try a blind side-by-side taste test, lest their house of cards comes crashing down and you no longer get invited back for steak.

January 2013

Read More

Read the original article on Serious Eats.