‘An entire community fell apart’: inside the Sheffield-set musical taking on Margaret Thatcher

Richard Hawley, the Sheffield-born singer-songwriter, is reflecting on the “strange, upside-down” nature of the modern music business. With streaming platforms now the norm and public attention hard to leverage, it’s a far cry from the Britpop fray he entered in the mid-1990s with a lesser-known band called Longpigs. He recalls how Shakespears Sister singer Siobhan Fahey once told him that: “Back in the day with Bananarama, they’d do four interviews, two TV appearances and sell millions of records. Now you do millions of TV appearances and interviews and sell two records.”

Not that Hawley, 57, seems too bothered about this state of play. A talented guitarist and vocalist, he has worked alongside some of the biggest names in music; supporting Radiohead and U2 (with Longpigs), collaborating with Nancy Sinatra, Paul Weller, Shirley Bassey, Pulp, the late Lisa Marie Presley, and others. But if he’s not a household name himself, that suits him fine.

“I’ll never do a TV ‘couch’ interview, it’d do my head in,” he tells me. “I don’t want to talk about what shoes I’m wearing. I know very successful people who aren’t happy with how they got there. For me, the whole point of my creative life is hitting the bullseye without aiming for it.”

Hawley has been writing songs almost since he could hold a guitar but he only struck out as a solo artist in 2001. Nine studio albums later, with a tenth on the way, he’s held in high regard by those in the know. He may not have troubled the singles charts, but he’s had four top 10 albums and twice been nominated for the Mercury prize.

His warm, tender-voiced, emotion-steeped songs combine grandeur and intimacy, blending country and folk strains with an urban sensibility to sometimes rousing, often melancholic effect. It’s as if he twinned the post-industrial North with bluesy, blue-collar America. “If you listen to a Johnny Cash song, he’s singing about railways and mountains,” he says. “You can transplant that to where I’m from, surrounded by hills, with the railway, and endless roads.”

When we meet, at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre, he looks as if he has stepped straight out of the 1950s: guitar in hand, dark shades, rockabilly quiff, rolled-up jeans. But musically, I suggest, it’s hard to say which decade he’s from. “Yes, I’d go with that, and wear it as a badge of honour,” he says. I had fretted he’d be gruff, given his political views are antithetical to The Telegraph’s, but he’s open, down-to-earth (“I’m obsessed with hoovering because I’ve got two dogs; it’s like a fluff factory”) and his own man, even popping out mid-interview for a leisurely cigarette.

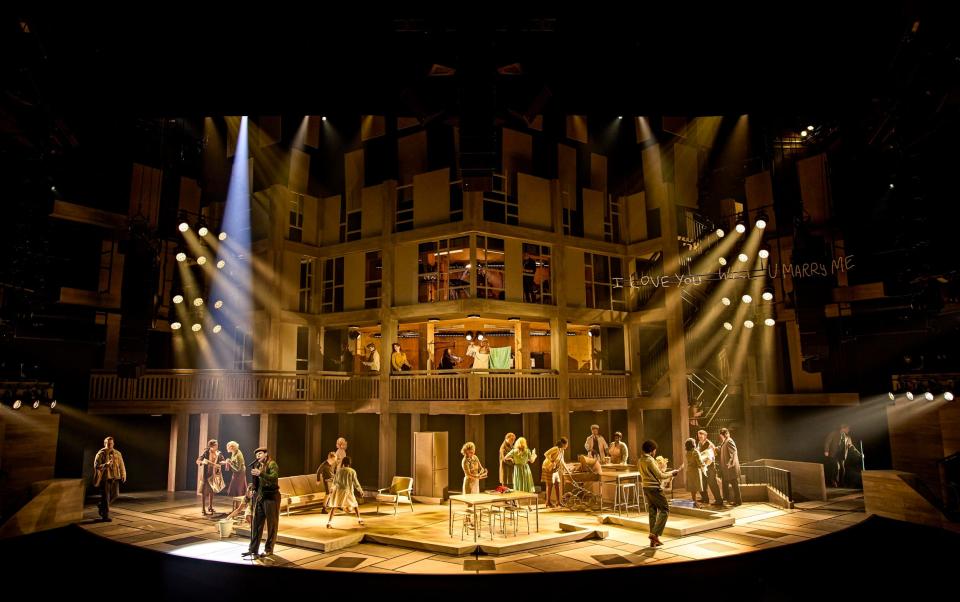

Those still unacquainted with his music have the perfect chance to discover it with the West End transfer of Standing at the Sky’s Edge: an unlikely hit musical, structured around Hawley’s back catalogue and set in Park Hill, a sprawling housing estate in Sheffield that abuts the city’s Skye Edge neighbourhood. With a book by local playwright Chris Bush, it started life at the Crucible in 2019, and was restaged last year at the National Theatre, winning two Oliviers.

Hawley’s initial reaction, on being approached with the idea for the musical by producer Rupert Lord over a decade ago, was disbelief. “It seemed ludicrous,” he says. “But I’ve felt like a salmon swimming upstream my whole solo musical career. I’m not cool or hip. It felt like the wrong thing to do, but I thought: F--- it!”

Hawley already knew Park Hill well because, he says, “one of my first girlfriends lived up there – I was very young, about 12 or 13.” And his maternal grandparents had lived in the crime-ridden slums that were cleared to make way for the brutalist estate after the war. So he warned Bush, who got the writing gig only after several attempts by others had stalled: “The minute you pull your punches, I’m gone”.

Equally, he notes, “it was important that it wasn’t a finger-wagging exercise.” And another stipulation: “Make it funny because Sheffield people are funny.” Hawley brought gags to the table as well as the songs. Bush tells me that he would sidle up “and say ‘Here’s a joke I heard at a bus stop’. The biggest laugh of the show is his – a joke about Sheffield Wednesday.”

By chance, one of the musical’s plotlines, concerning a 1960s steel-worker and his wife whose marriage crumbles under the stress of financial hardship, happened to mirror the experience of Hawley’s own parents. “I find those scenes really distressing to watch,” he tells me, “because they’re so like my mum and dad.”

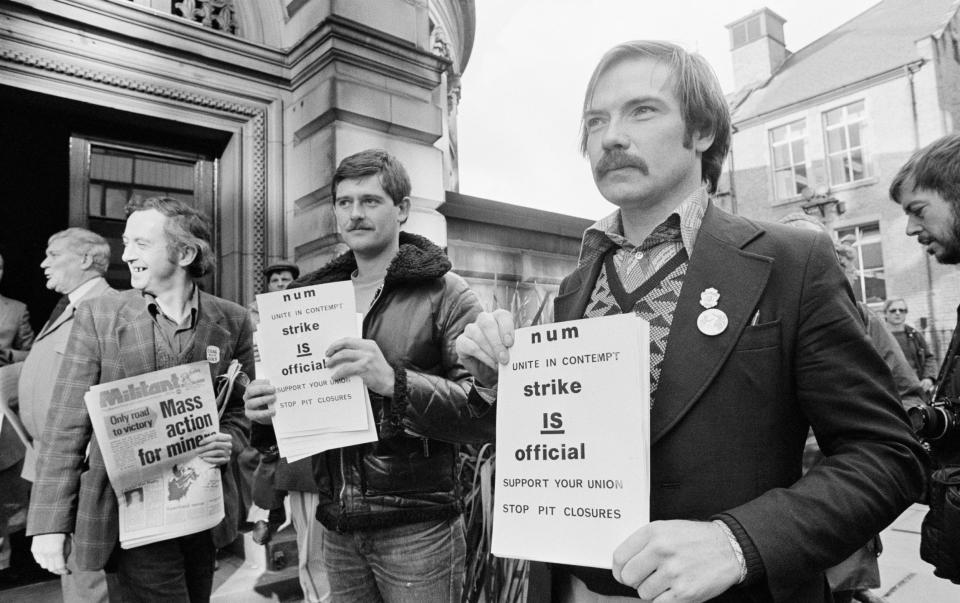

Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 election also features in the show; a moment when, for Hawley, “you became aware things were going to change. In Sheffield we had a red flag flying above the town hall. This is where the [political] hammer blow fell the hardest.” His father, Dave Hawley – steelworker by day, musician by night – was one of those affected by the mass job losses that hit the industry. “It f----d my dad up,” he says. “I saw an entire community dissolve; it fell apart in front of me.” His parents split up in 1983.

Hawley tells me that, despite its very specific setting, he can see why the contrasting feelings of struggle and community in Standing at the Sky’s Edge speak to a broader audience: “There’s a real sense of mourning and loss at the moment, it’s palpable. People feel alone and powerless to effect change. I think this musical reminds us of a different consciousness, something we used to have, holding onto what matters.”

Hawley grew up with two younger sisters in the working-class Sheffield suburb of Fir Vale. His mother Lynn was a nurse and a singer. His father (who died in 2007) was a gifted guitarist and singer of rockabilly and country music; in the 1960s, he played gigs alongside visiting US blues stars Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker. “My dad would work 12 hours in the steel works, come home, have a bath, eat, then get in a van and go and play in a pub or club,” Hawley says.

One of his father’s friends – and, later, Hawley’s godfather – was the international Sheffield sensation Joe Cocker. “They used to fit radiators together for the Gas Board and remained friends their whole lives,” he recalls. “Joe would come round the house. He gave me a lot of advice when I was a kid, usually in the pub after five pints.”

For Hawley, who left school after his O-levels, picking up a guitar to make a living wasn’t just a hobby; it was a necessity. “There was no choice, it was either shovel s--- or play rock ’n’ roll,” he says. “There was nothing for us in this city.”

At times, that path led him astray: his days with the short-lived Longpigs – whose 1996 hit On & On resurfaced recently on the soundtrack to the new TV adaptation of David Nicholls’s One Day – saw no little excess. “I did all the drugs, and was lucky enough to survive it,” Hawley tells me. “Others weren’t – there’s a graveyard out there of people who didn’t make it because they believed in the bulls--- and the drugs and the trappings of fame. That’s not even dust now,” he adds. “It’s 26 years since I’ve gone anywhere near a street drug.”

In the short-term, playing and touring in the late 1990s alongside his old pals in Pulp – whose bassist, the late Steve Mackey, Hawley had known since the first day at infant school – got him through. In the long-term, commitment to his wife (Helen, a mental health nurse), three children, and Sheffield itself has been the saving of him.

Yet, given his apparent contentment with marriage and family life, I can’t help being struck by how mournful Hawley’s songs tend to be. “Well, the past casts long shadows, that’s all I’m saying about it,” he says, then he grins. “Besides, the majority of happy songs are s---! Even Yellow Submarine gets annoying after a bit.”

In any case, he can’t imagine being happy anywhere but Sheffield. “I would feel like someone had torn my heart in two if I left this city to live somewhere else,” he says. “We have a lot of successful artists, but we’re unencumbered by any scene, by any one thing you’ve got to be. We didn’t have the Beatles, so there’s no benchmark – our history isn’t vertical stripes, we’re a bit more random polka dots. You can’t be ‘the Great I am’ here. No one gives a s---.”

Hawley loves that freedom: that he can still walk the streets of Sheffield whenever he chooses, soaking up inspiration, just a face in the crowd.

Standing at the Sky’s Edge is now in preview at the Gillian Lynne Theatre, London WC2 (lwtheatres.co.uk), opening Wednesday; Richard Hawley tours from May 24 (richardhawley.co.uk)