What, Exactly, Is Collectible Design Anyway?

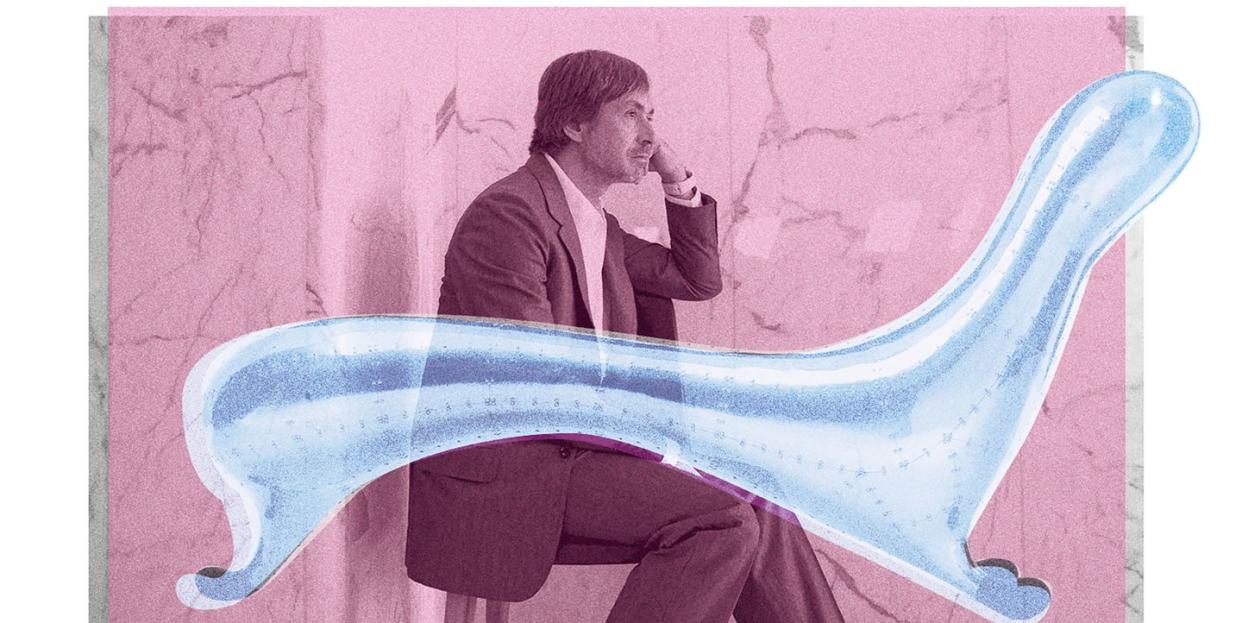

Above: Marc Newson and one of his Lockheed Lounges.

One can’t get away from the phrase collectible design these days. These two deceptively simple words joined forces nearly 20 years ago and have since gained steam, spawning a contemporary design market with an increasing number of galleries offering pieces touted as collectible—and the rise of a collector class wanting to be affiliated with this much-hyped movement.

Historically, collectible implied scarcity or provenance, and with vintage or antique pieces, scarcity was often a given, even if said works were originally mass-produced. But when it comes to contemporary furniture and accessories by living designers, it’s become a loaded word, implying that these pieces are worthy investments that will increase in value. But often the appreciation doesn’t occur for decades, if at all, and the secondary market for contemporary design is virtually nonexistent. Cordelia Lembo, head of the New York design department at Phillips auction house, confirmed that “many successful active contemporary designers have yet to establish a secondary market and therefore appear less frequently at auction.”

There are exceptions, most notably Australian designer Marc Newson. A prototype of his Lockheed Lounge, a sculptural aluminum-and-fiberglass chaise designed in the late 1980s, was auctioned for just over $2 million in 2010, setting a record for the highest price paid for a work by a living designer. In 2015, another of the edition sold for $3.7 million, and last year, his Pod of Drawers achieved $882,000 at Sotheby’s. Other contemporary makers seeing success at auction include Jeff Zimmerman, whose Vine ceiling lamp sold for $38,000 over the high estimate at Phillips last year. At the same auction the year prior, a pair of bronze tables by French artist Ingrid Donat sold for $100,000 over the top estimate. Donat is represented by Carpenter’s Workshop Gallery, co-owned by her son, Julian Lombrail; the gallery’s business model is built around offering editions of eight plus four artist’s proofs.

In today’s world of collectible design, limited editions are de rigueur, creating the perception of scarcity from the start. “It’s an approved artistic strategy,” says Glenn Adamson, a design curator and historian. Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, a curator at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and former creative director of the Design Miami fairs, where it is believed the term collectible design originated, tells me the design market came to fruition about 20 years ago to mimic the art market: “People thought craft just wasn’t sexy enough, so the idea was to embrace design as a term to create different types of interest, connoisseurship, attention, and increased monetary value.”

It clearly succeeded, what with all the design fairs that popped up. Yet using collectible design to describe offerings at said fairs is a tactic that every person I spoke to found problematic and hollow. “Something about it feels akin to the way luxury became overused to the point that nobody knows what it means anymore,” says David Alhadeff, founder of the Future Perfect, a gallery representing design darlings Chris Wolston and ceramist Eric Roinestad.

So why is the term still in use? Because nobody has coined a more acceptable phrase, according to Zesty Meyers, cofounder of R & Company, the gallery that catapulted the Haas Brothers to fame and currently represents the likes of Jeff Zimmerman, Katie Stout, and Roberto Lugo: “When the market exploded, nobody knew how to write about it. Does it go in a design magazine or the art section of the New York Times?” Damon Crane, founder of the gallery Culture Object, feels that “the term appeals to a certain class of people, and that’s not a bad thing, because we need them. I’m not saying let’s murder collectible design in its sleep, but I think we can do better.” Many have tried. For decades, what we now call design was referred to as the decorative arts, and while still in use the phrase seems to have fallen out of fashion, especially in the contemporary design world.

The irony is that the one word that truly speaks to the handmade nature of so many of these works is that other pesky term. Craft, Alhadeff says, is the “real crossover between the design and art worlds,” citing ceramics as an example. It may be time to take a cue from the jewelry market—which employs words ranging from fine to high as signifiers of both craftsmanship and price—and reclaim craft and attach it to the proper modifier.

In the meantime, the collectible design market continues to grow, and that is a good thing. “It is giving opportunities to a new generation, allowing new voices to emerge that might not have had an opportunity before,” says Lee F. Mindel, an architect and gallery owner. But he warns against buying to flip. “To go in with this notion that everything is collectible, wrapped in a bow as an investment piece, is foolish,” Mindel says. “The most important thing is that it has value to you in the present.”

This story originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of ELLE DECOR. SUBSCRIBE

You Might Also Like