EXCLUSIVE Patricia Urquiola: Back to the Basics

MILAN — Believe it or not, designer and architect Patricia Urquiola’s beginnings are rooted in textiles. She also has a penchant for rugs.

Born in Oviedo, Spain, in 1961, she graduated from Milan Polytechnic in 1989 with a thesis titled “Abitare come sistema (Living like a system),” which explored the technological potential of fabric. She envisaged a rug made of cables and a print she designed.

More from WWD

“Home textiles for me is never just about fabrics,” she told WWD.

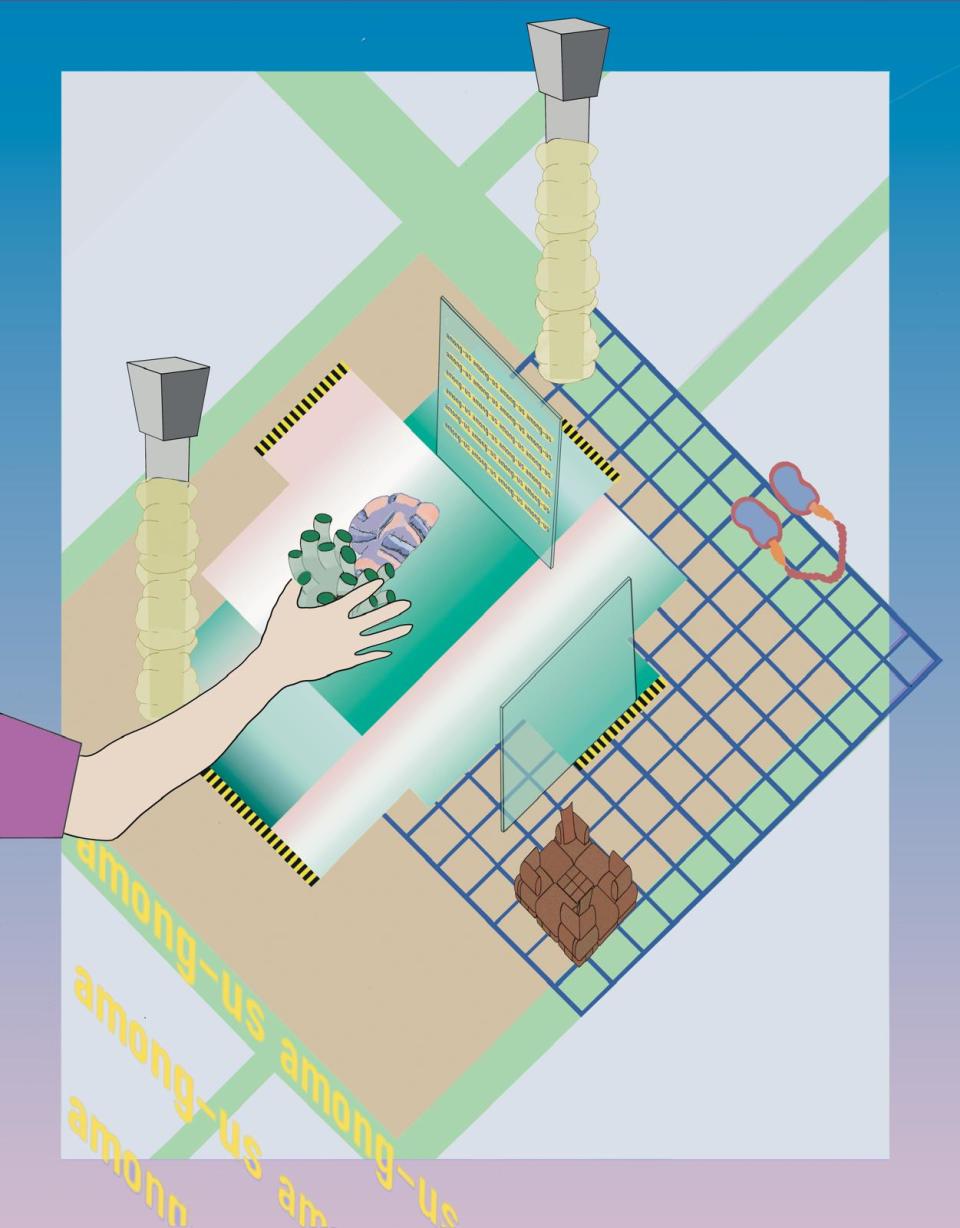

This week Urquiola has been a busy bee, unveiling a revamp of the Cassina store in Via Durini here, with new re-edits; a new marble bathroom for high-end natural stone specialist Salvatori; new pieces for Brazilian furniture maker Etel, and even a picnic basket with Milan-based jeweler Buccellati. She also unveiled Studio Urquiola’s upcoming project with the world’s largest home textile show, Frankfurt’s Heimtextil 2025 edition, at Milan’s Four Seasons Hotel on Friday. A preview revealed conceptual images of “Among Us,” which will put forth Studio Urquiola’s solution-driven textile research.

Mentored by Italian design pillars Achille Castiglioni and Vico Magistretti during his tenure at De Padova, the firm’s cofounder Maddalena De Padova taught her “that the textile side of home was fundamental.” Later she went on to work for Italian furniture and accessories group Moroso in 2000 and crafted the Gentry sofa, which was a segue into the world of furnishings.

All of these experiences were the basis for ambitious projects like the 2005 Ideal House exhibition in Cologne, Germany, with scaffolding made of embroidery that her team made by hand; the Wasting Time Daybed; the Recycled Woolen Island installation for the National Gallery Victoria Triennial, Melbourne, Australia, and the 2020 retrospective Nature Morte Vivante at the Madrid Design Festival. More recently, she collaborated with carpet specialist Desso on a carpet tile collection that is 100 percent recyclable, with a low circular carbon footprint. She has also designed artistic rugs for Italian company Cc-tapis and Denmark’s Kvadrat.

“The match between Patricia and Heimtextil is perfect because we continue to offer our services and lead the industry with our global platform for international audiences while highlighting innovations in the world of interior design and textile trends with the newest developments for the future,” said Olaf Schmidt, vice president textiles and textile technologies of Messe Frankfurt, the trade fair and event organizer behind Heimtextil. This new installation will be unveiled next year in Frankfurt from Jan. 14 to 17.

Here, WWD talks with Urquiola about her path and how we are living in the Age of Adaptability.

WWD: Why do you think you were attracted to doing textiles from the beginning?

Patricia Urquiola: I think it’s because it’s an element that always has incredible value, because it has this sort of mobility… The movement which is very interesting in relation to light and the way it feels to the touch… For me that is one of the ways I begin to understand a project. Woven textiles are also very interesting in the way each one already has a pattern, which is part of it from the time it’s created. A big wall with a curtain or a seat with various materials and textiles — they are kind of continuous, alive in a way.

WWD: You studied under Achille Castiglioni, who always said, “If you’re not curious, forget it. If you are not interested in others, what they do and how they act, then being a designer is not a profession for you.” How did this impact you?

P.U.: He always reminded us of that and it’s something that is quite clear if you want to pursue a creative path and do something. Obviously you have to have a capacity of observing and listening. You must really attract and try and understand and then see the other side to get answers. I speak with people and they say, “We are going to have a solution” for that briefing. But perhaps we just open the door to an argument which is going to give us room to breathe. I like when people understand that it’s not just the goal and how to solve it with regards to a product, but it’s about people being open to understanding that the path of possible creativity.

WWD: What was one of the biggest design challenges for you and how did you solve it?

P.U.: I did a hotel a few years ago and we were on the Caribbean island of Vieques [off Puerto Rico’s eastern coast] that really didn’t have anything [materials] on it. There was no way to make things arrive and it was so complex to reuse anything that was there, such as ceramic and wood. We had a problem with a bathtub and there was a container coming from Italy with some things that were so important for that moment and Agape, an Italian company, made us a bathtub that was made in metal out of very simple tin and at the last minute they arrived and we solved the problem. It’s beautiful how… sometimes needs turn into the beginning of a relationship and we have been working for them more than 20 years now. We’ve had many beautiful stories like this.

WWD: How would you define this artistic age we are living through, defined by the design world?

P.U.: Artists are always the first antennae for understanding and we are a world of designers, which is very near to the world of art. We work and are always thinking and re-thinking problems… the briefings… the solutions and what it means to solve things and how circularity comes into play and what we are doing. There are a lot of things on our path … But if you ask me…. there’s this book by Jeremy Rifkin, an economic and social theorist, which is “The Age of Resilience.” We are moving on a radical wave and rethinking the concept of time and space, refocusing the kind of age of resilience against the age of progress. It’s beautiful because efficiency is not really as important as adaptability.

WWD: In this Age of Adaptability, how is the industry point of view changing?

P.U.: I think the idea is to have a path that involves empathy and biophilia, which is certainly crossing our minds as to how to approach everything. I think it’s obviously complex and there are other arguments on sociology and philosophy that are crossing paths and then there’s technology. Technology is just a tool. I think that design is education for young generations and it’s interesting because it’s a way of thinking that is a discipline or a way of life because it always provides the right attitude as to how to rethink things in a pivotal moment. From the moment we are awake in the morning… you know I read the news on my iPad and I say “OK, here we go today again.”

WWD: From your projects spanning from designing furniture for Cassina to designing the interiors of a yacht for Sanlorenzo, what sort of way of life are you trying to promote?

P.U.: I think there’s no answer to this. It’s about the path. You need the elasticity to grow into your many contradictions. In this moment it is very important to be open to this amid those moments of disruption… I think within the time we are living, there is a lot of hybridization and spaces with a lot of experiences and functions that cross the way we live, our public and our private lives and this is very important. Those shelters are more permeable and I think that it’s interesting that they were going to be more focused on service than objects.

WWD: What is shelter to you?

P.U.: They aren’t solid anymore… our old constructed walls, because today we have digital shelters. The digital and the physical both have different metrics but we have to be open to understanding and rethinking and being elastic. For example, textiles. Textiles could have a very important voice in this passage to new shelters. I think it’s more about mobility and density and the traditional way of creating our limits.

WWD: What materials are you most excited about now?

P.U.: I think any redefinition of material, which is biomaterial, is fundamental. We have to create with new material from bioplastic, to bio waste materials for bricks or fabrics. At the same time there is a lot of research out there and the universities and companies are at just the beginning of a long path in their research of bio materials.

WWD: You talk a lot about a path. Was there an instance that really changed your path?

P.U.: A few times things didn’t arrive in the right place and they weren’t as good as I thought they should be and we didn’t achieve the right solution. I think those things made me grow a lot. It’s really important that you enjoy the process. You need to have this resilience or getting into the process of re-thinking and rethinking. Take designing a chair, for example, which is a solution for rest…. They’ve been done for so long but there are always new ways of sitting and there are new ways about using other materials. It’s not about the seat, it’s about the way of living that thing.

Solve the daily Crossword