Fantastic Beasts, Best British Film? The 10 most bizarre Bafta nominations ever

This year, barring one of the biggest upsets in its 77-year history, the Baftas will be lauding Christopher Nolan and Oppenheimer, in what will likely be a dress rehearsal for the Oscars next month. Although Nolan and his film are worthy and deserving winners, it is hard not to feel a faint sense of weariness at the all-but-inevitable coronation, especially because the Baftas have – shall we say – a reputation for throwing curveballs out there.

The last time that there was a genuinely unexpected award came in 2022, when Joanna Scanlan deservedly won Best Actress for her performance in the low-budget British picture After Love; the Oscar that year went to Jessica Chastain, for playing Tammy Faye, and Scanlan and her film were not even nominated.

Historically, the Baftas have always been intended as a celebration and recognition of British cinema, and this has often seen what might be regarded as a provincial and parochial attitude when it comes to the nominations. Looking back over the past few decades, especially, there are a number of people who were recognised – and in a few cases, even won – who seem perplexing, even perverse candidates for this acclaim.

As the Baftas have attempted to overhaul their eligibility for awards over the past couple of years, it is possible that we will never again see some of these bizarre and perverse nominations. This is an enormous shame for any connoisseur of watching an eminent awards body going slightly mad in public. Here are ten of the occasions that the Baftas made decisions for reasons best known to themselves, and the rest of us can only speculate as to why.

1. The Bourne Ultimatum is nominated for Best British Film (2008)

Matt Damon’s third Jason Bourne film is rightly regarded as the highlight of the series, a tense and kinetic thrill-ride directed with maximum flair and skill by Paul Greengrass. It was entirely appropriate that it should be recognised at the 2008 Baftas, and it was nominated for Greengrass as Best Director along with a whole host of technical categories; it deservedly won for Best Editing and Best Sound. There was, however, one truly strange nomination, and that was that it was up for Best British Film.

Not only was it mainly funded by the American studio Universal, with some German money, but apart from the presence of the British Greengrass and an unforgettable early set-piece at London’s Waterloo station, it doesn’t even have any links to the United Kingdom. Technical error or desire to recognise an excellent film in a less competitive category than Best Picture? Who knows.

2. John Hurt is nominated for Alien (1980)

Ridley Scott’s breakthrough picture Alien remains a sci-fi horror masterpiece over four decades after its release, and one of the most influential films ever made. Few, however, would ever describe it as an actors’ showcase; by far the most memorable performance is given by its default lead, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley, who would have far more to do in the eventual sequel Aliens. Yet at the 1980 Baftas, John Hurt – who had won the award for Best Supporting Actor for Midnight Express the previous year – was once again nominated for his appearance as the ill-fated Kane.

Although he has a spectacular death scene, which is more a feat of special effects than performance, one would be hard-pressed to describe Hurt (who replaced an indisposed Jon Finch) as being truly indelible in the role. In any case, he lost to Robert Duvall for his scene-stealing performance in Apocalypse Now.

3. The entire Best Supporting Actor roster (2002)

For some strange reason, the Bafta membership decided to go wildly off-piste when it came to the 2002 awards. Jim Broadbent found himself in the unique position that year of winning the Oscar for his subtle, moving work as John Bayley in the biopic Iris, and of being awarded the Bafta for his over-the-top showboating as the impresario Ziegler in Moulin Rouge; he was not even nominated for Iris, although his co-star Hugh Bonneville, playing the young Bayley, was.

Yet it’s the others in the category who are the real head-scratchers. Robbie Coltrane – a regular Bafta winner for his performances in the TV series Cracker – was nominated for his charming but hardly revelatory work in the first Harry Potter picture, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, and Colin Firth was in the running for his stiff appearance as Mark Darcy in the first Bridget Jones’ Diary, rather than his far more charismatic and entertaining co-star Hugh Grant in the same picture.

And, most bizarre of all, Eddie Murphy was nominated for a Bafta for his vocal work in Shrek; his Donkey was great fun, but award-worthy? Hardly. The Oscars, meanwhile, recognised far more memorable performances including Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast, Ian McKellen’s Gandalf in Fellowship of the Ring and Ethan Hawke in Training Day: a clear example where the Academy got it right and Bafta very much didn’t.

4. Nocturnal Animals almost sweeps the board (2017)

Designer-turned-director Tom Ford’s follow-up to his much-lauded picture A Single Man didn’t attract the same level of acclaim that his debut did, with most critics dividing between praising the film’s ambition and describing it as – in the indelible words of Victoria Coren-Mitchell – “a piece of gynophobic death-porn”. It received some limited attention at the Academy Awards, where Michael Shannon was nominated for Best Supporting Actor, and the Golden Globes, where Aaron Taylor-Johnson won in the same category. But when it came to the Baftas, the organisation all but rolled out the red carpet for Ford and his film when it came to lauding it.

Nocturnal Animals received no fewer than nine nominations, including Best Actor for Jake Gyllenhaal, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay for Ford and a host of technical awards. Whether Bafta members really believed that it was one of the year’s outstanding films, or were just desperate for Ford to turn up at the ceremony, is impossible to say, but come the actual awards, it went home empty-handed, beaten by La La Land in most of the categories it was nominated in.

5. Zero nominations for Best Director nominations (1986)

The Best Director award is traditionally the second most prestigious at the ceremony, coming only after Best Film in terms of impact and importance. So it was utterly perplexing that, at the 39th Bafta ceremony in 1986, there was simply no award given for Best Director, and no shortlist either. It’s not as if the year was short of possibilities – Woody Allen won Best Film for Purple Rose of Cairo, and the likes of Robert Zemeckis (Back to the Future), Milo? Forman (Amadeus), Peter Weir (Witness) and David Lean (A Passage to India) would all have been worthy recipients, too, in what was one of the stronger assortments of directorial talent in the decade.

There is an explanation, albeit not a particularly convincing one. According to a Bafta spokesperson, “the Best Film and Director categories were merged into a ‘Film’ category for the 1986 Film Awards. The producer and director were awarded within Best Film that year.” It was a strange, rather than innovative decision, and it was little wonder that the Director award was reinstated the following year, when Allen won for Hannah and Her Sisters.

6. Eighteen nominations for Best Film (1962)

Most years, Bafta nominates five or six films for Best Picture, which allows for a tight focus on the outstanding pieces of cinema of the previous year – although the Best British Film award also allows some excellent but under-the-radar pictures to be recognised, too. However, in the earlier years of the award, Bafta would allow a vast number of pictures to be nominated in the category, which led to what can only be described as a mild form of chaos.

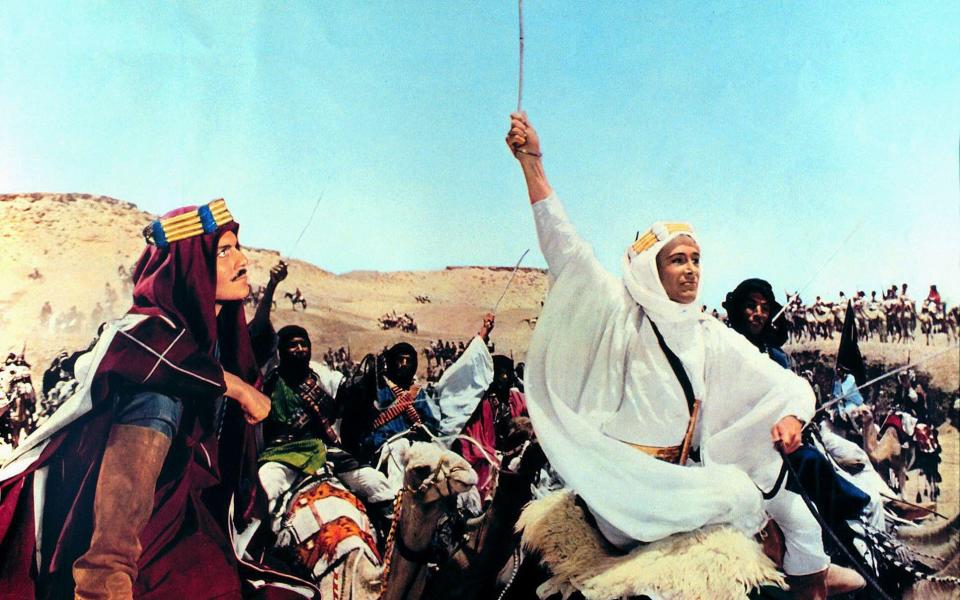

In 1957, for instance, everything from Laurence Olivier’s distinctly lightweight The Prince and the Showgirl and the forgotten thriller Windom’s Way were up for the same award as Robert Bresson’s existential classic A Man Escaped and Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. After a particularly swollen selection of 18 nominees in 1962, in which Lawrence of Arabia won over the likes of Jules et Jim, Lolita and West Side Story, the category was trimmed down, firstly to a more manageable 12 the following year, and then, from 1964 onwards, a far tighter four or five nominations that usually (although not always) recognised the best films of the year, rather than makeweight ones.

7. The Full Monty over LA Confidential – and Titanic (1998)

There can be no doubt that The Full Monty, which was for a while Britain’s highest-grossing ever film, is an enormously enjoyable and uplifting comedy that deserved the acclaim it received. Yet one tendency that Bafta has always had is to roll out the red carpet for British pictures (and talent) that it believes should be recognised, and to ignore far superior and more important works of cinema in the process.

Rather than give The Full Monty the award for Best British Film that it clearly merited, it was awarded Best Film over the far more consequential L.A Confidential and Titanic. In the rush to give it as many prizes as possible, Robert Carlyle and Tom Wilkinson were handed Baftas for their performances which even they might have conceded were not necessarily their most deserving work. Amusingly, Titanic, which swept the Oscars that year, did not receive a single Bafta; proof, perhaps, that the voting body were less impressed by James Cameron’s behemoth than many others were at the time.

8. Fantastic Beasts is nominated for Best British Film

Bafta has always had a penchant for lauding successful British exports in their nominations. Both Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and the series highlight Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban received nominations for Best British Film, and many would suggest that the final Deathly Hallows picture should have been similarly lauded, perhaps even a worthy winner. It was not to be, and so, perhaps in recognition of this, the first of the Fantastic Beasts spin-off pictures, Fantastic Beasts and Where To Find Them, was nominated in the category in 2017, along with a host of technical awards.

There was only one minor problem with this, and it had nothing to do with the subsequent controversy that its creator JK Rowling has been involved in; it really isn’t a very good film and didn’t deserve such recognition. Although it was very successful at the box office, it made considerably less than the Harry Potter franchise, before the follow-up films were financial and critical flops. It lost to Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake – a film that could not have been more different, featuring precisely no fantastic beasts or lavish special effects. In the year that Mel Brooks was awarded the Bafta fellowship, it is hard not to wonder whether someone, somewhere was having a laugh.

9. Judi Dench for absolutely everything (various years)

Bafta has certain actors who it likes to recognise repeatedly, to near-talismanic effect. The great Denholm Elliott, for instance, was nominated for Baftas seven times between 1973 and 1986, and won three years on the trot, from 1983 to 1985. Yet it is surely Dame Judi Dench who Bafta have lauded more than any other performer, save the similarly ubiquitous Meryl Streep. After first recognising her as Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles in 1965 for her performance in the film Four in the Morning, Dench had to wait two decades to achieve her due, but then it barely stopped coming. Between 1985 and 2013, Dench was nominated for either Best Actress or Best Supporting Actress a staggering 14 times, winning five of them.

Some of these awards were richly deserved, such as her brief but scene-stealing performance in Shakespeare in Love as Elizabeth I, but many of the others had the feeling of rote predictability, especially as many of the nominations came for indifferent work in Harvey Weinstein-produced would-be prestige pictures as Chocolat and The Shipping News. Dench has continued to act prolifically for the past decade, but for some reason, Bafta has fallen out of love with her, and her performance in 2013’s Philomena is the last time that she received recognition. Nevertheless, her abiding status as one of Britain’s most beloved actresses is surely compensation for not having been nominated for, say, Victoria & Abdul or Belfast.

10. The extremely random awards for Best Supporting Actress (various years)

Bafta has always played its hand relatively straight when it comes to the Best Actor and Best Actress categories, but when it turns to the Best Supporting Actress department, it is often difficult to wonder what on earth its voters were thinking. John Boorman’s excellent Hope and Glory won a Bafta for Susan Wooldridge, while Sarah Miles and Sammi Davis’s far more memorable work in the same film was not even nominated.

And on and on it goes; the veteran character actress Elizabeth Spriggs was somehow, inexplicably, shortlisted for her brief performance in Sense and Sensibility (losing to her co-star Kate Winslet), Maria Aitken was nominated for appearing in A Fish Called Wanda for a few inconsequential scenes as John Cleese’s strait-laced wife. And this is before we even get onto the bizarre decision to award Rosanna Arquette Best Supporting Actress for what is clearly a lead performance in Desperately Seeking Susan.

Sanity has largely prevailed since the turn of the millennium – you’d have to go back to Maggie Smith winning for 1999’s Tea with Mussolini for a really bizarre award in this category – but it is yet another reminder of the intrinsic eccentricity of Bafta. It may now be a slicker, more corporate entity, but perhaps something quintessentially British has been lost in the process, too.