The Flying Pig: the fight to save the pub where Pink Floyd were born

In the early 1960s, there was a band from Cambridge named The Redcaps. Originally a skiffle group, they moved towards the more exciting rock ’n’ roll sounds coming from America – their name was even a nod to ‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’ singer Gene Vincent’s band, The Blue Caps – before signing to Decca Records and in 1962 releasing a single, ‘Stormy Evening’. It’s a good slice of early-1960s pop, if a somewhat lost one.

The Redcaps would rehearse in a room above The Crown, a boozer’s boozer located near the city’s railway station, run by singer David Parker’s parents. It was this, heard from the street outside, that drew a young man into the pub, asking the landlord if he might sit in and watch them play. David recognised the young man, with whom he’d occasionally hang around in the city centre at weekends. The boy’s name was Roger Barrett, but you know him as Syd, and this was the first time the future Pink Floyd guitarist had seen a proper electric rock band playing live.

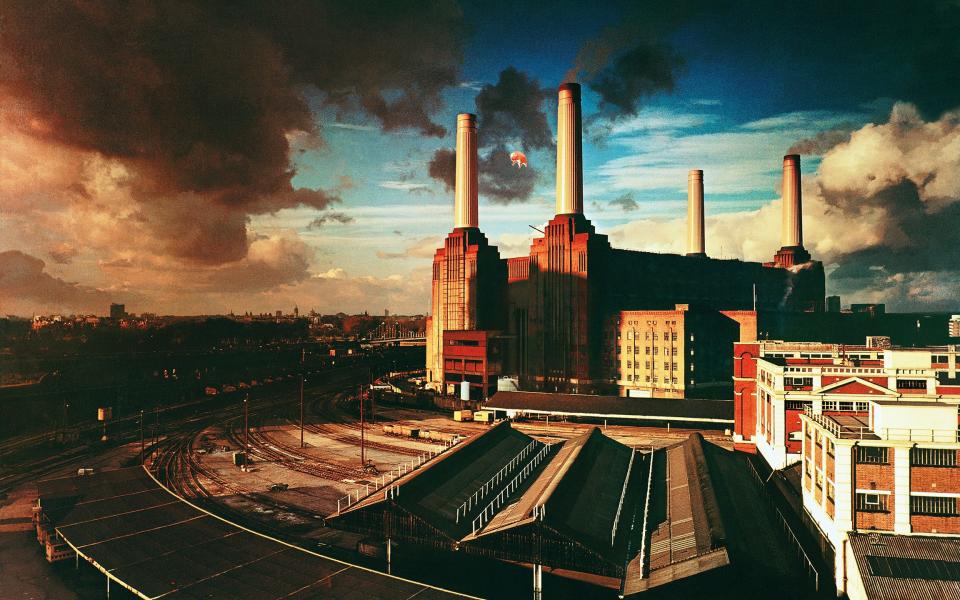

Syd is also said to have met another musical David in The Crown: Gilmour. And so, as time turned tale into part of the legend of Pink Floyd, so too did the pub become known for its ties to the band, particularly with its name change in the late 1980s to The Flying Pig – a play on then-landlord Mick Clelford’s old pilot nickname, “The Pig”, as well as a more obvious Floydian reference to the cover of 1977’s Animals.

Around Cambridge, The Flying Pig is known as a singularly wonderful place. Its history is good, but its present equally so. Most nights of the week, the blue pub hosts gigs – rock, jazz, blues, folk, odd stuff that wouldn’t fit anywhere else. Even during lockdown, there were over 100 of them. When they needed a bit of support when they couldn’t open, they quickly raised over £20,000.

But now The Flying Pig is in trouble. Having stood for 144 years and survived Covid’s tight squeeze on the pub business, it faces doom in its most mundane form. On June 7, having been under threat for a decade, landlords Matt and Justine Hatfield were given notice that their lease on the pub, in which they have lived and worked for 24 years, would be up in six months.

With bitter irony, while the pub itself has remained a viable business over the past 17 months, it must now make room for something that remote working has proven, in many cases, to be redundant: it’s being turned into offices.

“Our lease wasn’t due for renewal until June 2022 – at present we are being evicted on October 27,” says Matt Hatfield. “The developer is planning at this point to demolish the whole building, as the most recent planning application that kept the fa?ade of the pub but would result in closure for three-and-a-half years was refused by the council.”

Previous attempts to develop the site were met with strong opposition, and in this latest round, it’s been a similar story. “The community have been very vocal about their wish to keep The Flying Pig open,” he adds. “They created an online petition that gained 16,000 signatures opposing the demolition of the pub and live-music venue. Many local political parties have stated their own opposition to the closure of such a valued community asset, and we even got a mention in Parliament by [former Cambridge MP] Julian Huppert.”

The Flying Pig isn’t just a pub – it’s a home. For almost a quarter of a century, the Hatfields have made the place their lives’ work. They even met there, while Justine was working part-time behind the bar and Matt was studying Fine Art at university. When they married, it was the venue for their wedding reception (of course), and it’s where they’ve raised their two daughters.

This homeliness is why people love The Flying Pig. One is local musician and former BBC radio broadcaster Nick Barraclough, who has been drinking there since the 1980s and has written a book on its history, A Disorderly House. On Christmas Eve, he performed in the pub’s garden (“It was freezing – literally, sub-zero”), and is another for whom the pub represents the greatest parts of pubbing: community, friendship, entertainment, life.

The pub had been through many facelifts since it was initially opened as The Engineer in 1844, when it served the workers building the first railways. In the 1980s, as Mick Clelford took over, he took out the “damp, scruffy plush carpets and flock wallpaper” (according to Barraclough), and brought in a new, cooler style, and leaned into the musical end of the remit. When the Hatfields took over, it was the perfect coupling.

“Usually, when you play in a pub, you’ll go in and you’re barely noticed by the people running it, because you’re there to bring in the punters,” says Barraclough. “With Justine and Matt, they’re more interested in your gig than they are in selling beer. I’ve been in sometimes, been setting up for the gig, and said, ‘It’s a bit quiet tonight’, and Justine’s said, ‘Well I hope it stays like that, so I can concentrate on the band.’”

It’s stories like this that make the future closure of The Flying Pig such a blow. Places like theirs are hard to grow, all-too-easy to get rid of, and almost impossible to replace. They are not just an anywhere with beer pumps and the dimensions in which to fit musicians and tables and seats, but a place with a life and history of its own – what Barraclough calls “a vibe”.

But this is the way of all things now, it seems. Regardless of the fact that The Flying Pig is a much-loved community asset, a pub that, even in a city as steeped in culture and art as Cambridge, manages to stick out as unique both for its past and its present, the developers have got their wish.

It’s something Barraclough has seen a depressing number of times. “I was born in Cambridge 70 years ago, and over those years I’ve seen swathes of the city destroyed by developers,” he says. “One particular area, The Kite, was destroyed in the 1970s. It was rows of little Victorian streets, lovely streets, that they destroyed to build a massive shopping centre [The Grafton Centre], which is now being sold because nobody goes there. It beggars belief.”

He sighs. “One band I’m in isn’t going to get any gigs when they close. It’s the sort of band that doesn’t fit in your average pub or small venue, so we play regularly at The Flying Pig, and the band will just have to stop. That will be it. And we won’t be the only ones. A lot of musicians rely on it as their place to get out, and a lot of bands exist now because of the pub – because they met other musicians there.

“An awful lot of bands, and consequently recording artists and writers, simply wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for The Flying Pig. If it goes, it’s going to be an absolute tragedy.”

For now and for the next few months, for the Hatfields, The Flying Pig remains the same as it has for the past 24 years: a family home that guests come to visit every day for drinks, music and laughter. After that, there’s a question mark, even the tiniest sliver of hope that the diggers can be stopped.

“We can’t quite imagine our world without this place, and will need to take some to consider what comes next,” says Matt Hatfield. “We desperately hope that some kind of resolution can be found between the community of Cambridge and the developers which would keep The Flying Pig’s doors open and the music playing.”

But even though places like theirs can’t be replaced, if the pig has flown for the final time, you can take the landlords out of their pub, but it’s much harder to take the pub out of the landlord.

“It’s not impossible that we would start again somewhere else,” he says. “Life without the music is not an option.”