What The Gilded Age Gets Right About Infamous Architect Stanford White

Up until the very minute he was shot on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden, Stanford White might have considered June 25th, 1906, to be a good day.

White, 52, the defining architect of the Gilded Age, the man who helped design Madison Square Garden itself, was sitting at one of the best tables that the rooftop theatre afforded, listening to the song “I Could Love a Million Girls,” when millionaire playboy Harry K. Thaw walked up to White’s table.

Minutes later, as White lay bleeding on the floor, Thaw announced, “I killed him because he ruined my wife.”

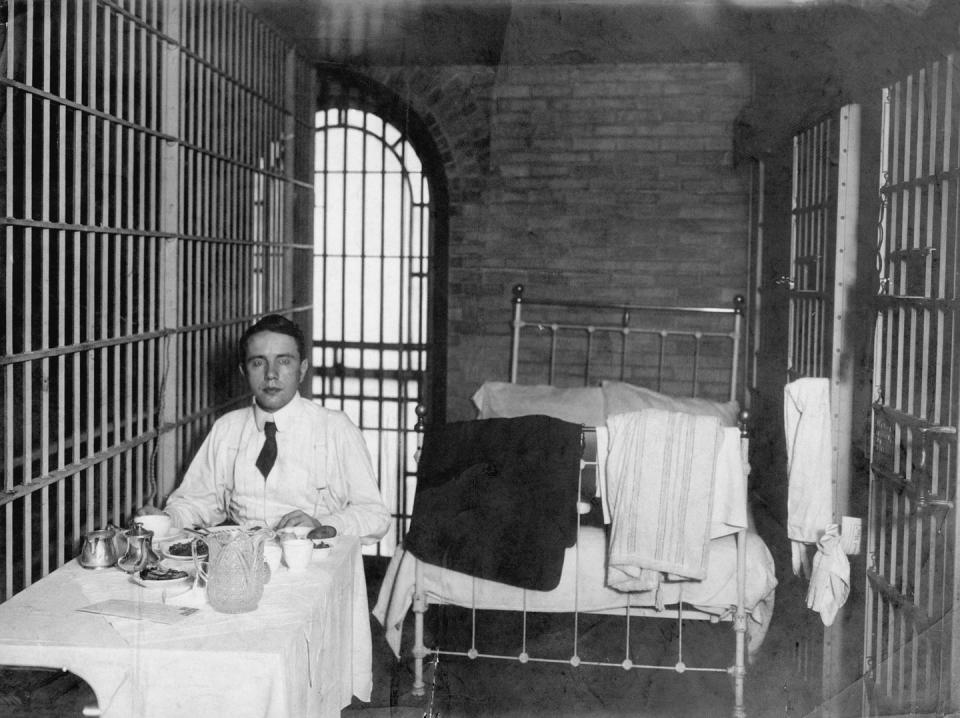

The murder trial of Thaw, husband to gorgeous young showgirl Evelyn Nesbit, was the first to take on the description “Trial of the Century.” The courtroom revelations of White’s brutal seduction of Nesbit when she was 16 shocked and horrified America. In a country still abiding by Victorian standards, debauchery was supposed to be carefully hidden. Laying bare the lifestyle of White—by no means alone in his womanizing, heavy drinking, and overspending—helped usher in the twilight of the Gilded Age.

One of the ironies of Stanford White is that the man whose life was raked over in an ugly and sordid trial had devoted decades to celebrating what was most beautiful in architecture and art—and to celebrating New York City, the city he adored. The Washington Square Arch, the Metropolitan Club at East 60th Street, the Judson Memorial Church at 55 Washington Square, the Villard Houses at 455 Madison Avenue, the Players at 16 Gramercy Park South, and the Bowery Savings Bank are just some of his achievements.

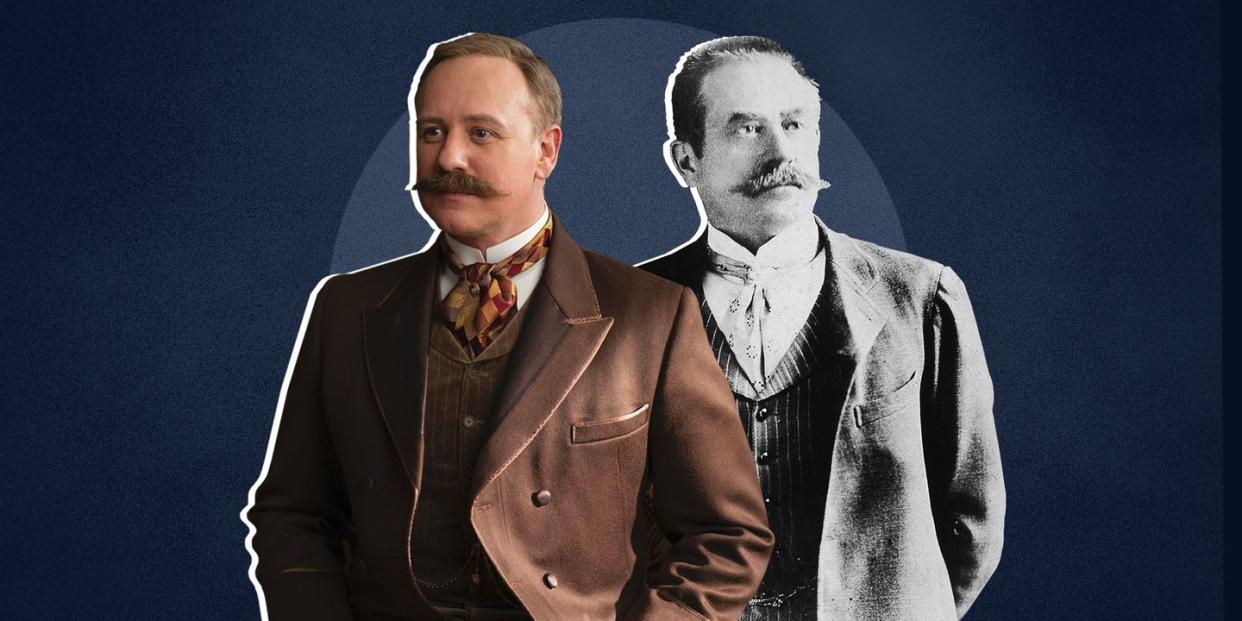

As the series The Gilded Age, now streaming on HBO, makes clear, in the 1880s, Stanford White—who’s played on the series by John Sanders, and is summoned to supply his architectural magic for established society and gatecrashers alike—was the man to call in when someone with a fortune wanted to build a deeply impressive home. He was hired by Astors, Vanderbilts, and J.P. Morgan. He was also hired by those people with “new money.” White moved between the two groups with ease.

Debra Schmidt Bach, curator of decorative arts and special exhibitions at the New-York Historical Society, tells Town & Country, “The artistry, size, ornament and structures of [White’s] buildings embody the energy and optimism that many felt the Gilded Age held for the United States.” In other words, he was the perfect man for his era.

White himself did not spring from “old New York” or from new money either. His father, Richard Grant White, “was a cranky bohemian who fancied himself an English gentleman yet was blackballed from the Century Club and was chronically broke and in debt, who had studied to be a doctor and also passed the bar but was, in practice, a music critic, a Shakespearean scholar, a linguist, a lecturer, a cultural gadfly, a sonneteer and an employee of the Custom House,” wrote Suzannah Lessard, the great-granddaughter of Stanford White in her bestseller The Architect of Desire.

Stanford attended public schools, a fact he denied later, saying he had been privately tutored. White in fact had no formal architectural training, which was not that unusual for the 19th century. He worked as an apprentice to Henry Hobson Richardson, and toured Europe, before joined two young architects, Charles Follen McKim and William Rutherford Mead, to form the firm McKim, Mead and White. He also married Bessie Smith from a prominent Long Island family.

“White's most significant contribution to New York City and American architecture was vision,” says Bach. “White was well versed in European classical art and architecture of the period and saw the possibilities that Beaux Arts forms and vocabulary symbolized for the United States during a period of massive economic expansion.” McKim, Mead & White designed hundreds of civic, commercial and resort and club buildings, public art structures, and elaborate private homes.

“Well versed in art, antiques and architecture, White designed buildings that were not simply dressy evocations of Gilded Age wealth, but also reflections of the seismic industrial changes that occurred following the Civil War and the possibilities that new building, transportation, and communication technologies held for a country also in the midst of huge demographic growth,” says Bach.

White was indefatigable, socializing whenever possible not just because he richly enjoyed the city’s entertainments, but he made contacts for McKim, Mead & White. Lessard said that at the firm, White was “tolerated because of his charm—powerful when he turned it on—and his overflowing giftedness. He was the baby of the office, a big, inspired toddler, indulged, angelic, oblivious, tyrannical.”

His creations can be found outside New York City. He designed Rosecliff and several other houses in Newport, Rhode Island, and the Frederick Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park, New York. The firm’s Boston buildings included the Algonquin Club, the Boston Public Library, Harvard Stadium, and the Symphony Hall. His work on the University of Virginia is considered one of his few misfires.

White’s dissipated dark side was no secret to his friends. He was a predatory seducer of teenage girls, seeking out actresses or dancers who were from impoverished families. Evelyn Nesbit fit the profile perfectly. After befriending her and her mother as a supposed benefactor, White paid for the mother to visit relatives out of town and then insisted Evelyn, 16, drink a great deal of champagne, which may have been drugged as well. She passed out to find herself naked in bed next to a naked Stanford White.

The details of Nesbit’s trauma were coaxed from her at court to help build a defense for her mentally unstable husband. But other shocks were revealed. White would have been dead within the year if not murdered. He suffered from Bright’s disease, his liver was in terrible shape, and he had incipient tuberculosis. Not only was his health nearly destroyed by his way of life, but he was close to broke. Yawning underneath the Gilded Age veneer was a canyon of debts.

“He was known to believe that he should live as well or better than his wealthiest clients,” says Bach. “His charming personality and reputation for lavish living brought him wide public visibility, including among Americans who otherwise may not have known about his architecture or heard much about his exploits.”

White’s rise and fall are echoed in the tragedies of certain public figures in the 21st century. As Bach says, “His extravagant lifestyle, and lack of discretion or concern for those who were impacted by his actions, despite producing outstanding work, has much in common with some of the high profile, publicity-seeking business and artistic innovators who exploit media attention today.”

You Might Also Like