‘God would dig me like crazy’: how Marc Bolan spun out of control

They called Marc Bolan a visionary, but how dark did his premonitions get? They say, on a visit to the Louvre, he was engrossed by a Magritte painting of a sycamore tree in moonlight called The Sixteenth Of September. As obtuse as Nostradamus, he sang of a “hubcap diamond star halo” and that “life is the same as it always will be, easy as picking foxes from a tree”.

On tour in 1967 it’s said he role-played a future in which he was world famous with his manager Simon Napier-Bell. “Of course, I’d have to die in a car crash like James Dean or Eddie Cochran,” he said, “then my records would sell much more.” “In a Rolls-Royce?” Napier-Bell asked. “No,” he replied, “in a Mini.”

Ten years later, after a night of champagne with friends at Morton’s drinking club in Berkeley Square, Bolan and his partner Gloria Jones set off home in a purple Mini 1275GT – registration FOX 661L. Less than a mile from Bolan’s house in East Cheem, the Mini crashed into a chain link fence post on Barnes Common, coming to rest against a moonlit sycamore tree. Jones escaped with leg injuries and a broken jaw and collarbone. Bolan, aged 29, died instantly. The date was September 16, 1977.

Did Bolan – the swan-riding mystic prince of psychedelic wizard folk who envisioned a glam rock world full of electric warriors boogieing around in feather boas and mirrorball top hats, and is now celebrated with an all-star tribute album – foresee his own death too? Paul Roland, author of the biography Metal Guru – The Life and Music of Marc Bolan, is open-minded.

“Who knows how pre-destination works?” he says. “He was afraid to die in his sleep. When he was living with June [Child, Bolan’s ex-wife] he’d get her to wake him every hour just to see he was okay. He had this nagging apprehension about dying too soon.”

If Bolan somehow sensed tragedy in his future, he also saw stardom. Born Marc Feld in Hackney in 1947, he grew up as what Roland calls “an East End chancer”, helping out on his mother’s Berwick Street market stall and hanging around the stage door of the Hackney Empire to glimpse his teen idols and, one time, help carry Eddie Cochran’s guitar.

As a teenager he became a model and mod “who wanted to be a star above everything else”. The minute he could drink, he’d frequent music industry hangouts declaring himself the next Elvis.

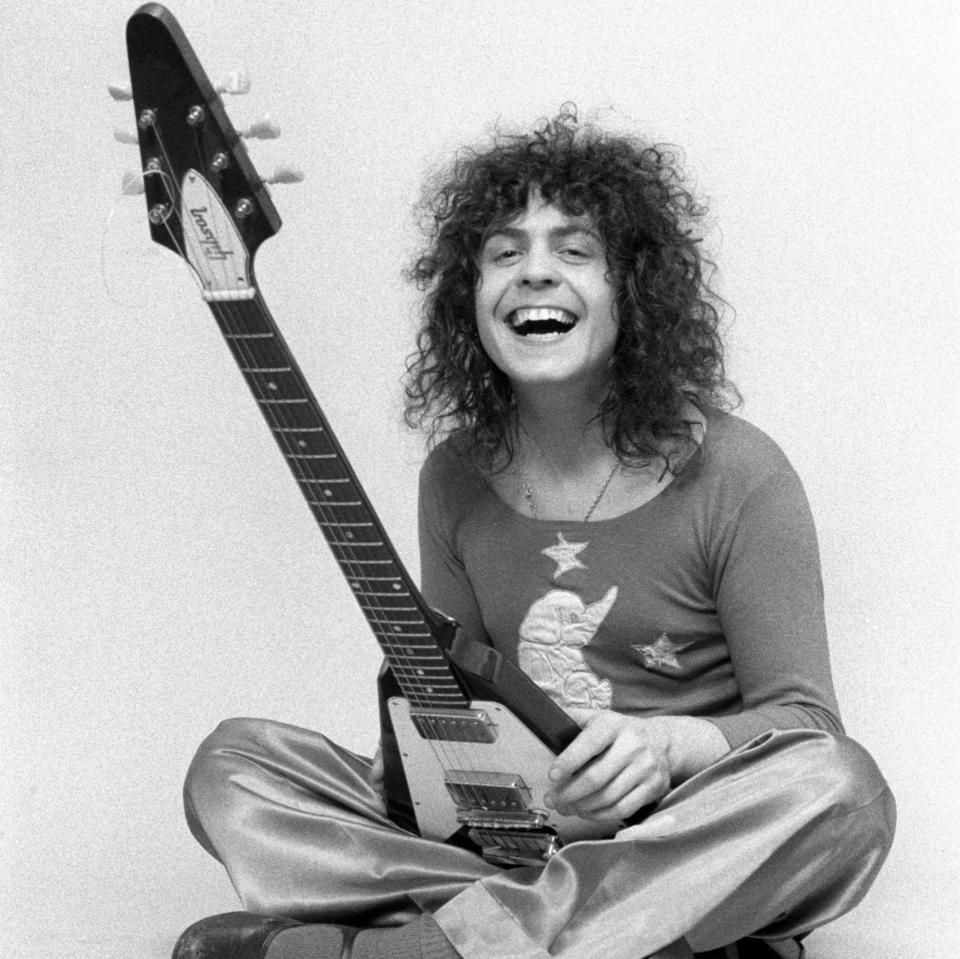

Marc Feld was a sensitive, introverted cockney kid with dyslexia and crippling stage fright; Marc Bolan, the rock god alter-ego who danced himself right out the womb to release a debut single called The Wizard in 1965, was the posh-speaking, supremely confident pop dandy and poet that Feld wanted to be. “Marc Bolan was this person that he created and could hide behind because he was s___-scared of going on stage,” Roland says. “All he was was his alter-ego. He was living this fantasy, the cosmic dancer.”

Bolan swiftly consumed Feld. Friends and colleagues spoke of Bolan as having “terrifying” self-conviction and a strong fantasist streak. As his first albums alongside Steve Peregrine Took as Tyrannosaurus Rex build him a cult club following with their Tolkeinesque tales of unicorn lovers, mages, dragons and druids – often played on a battered £12 guitar, bongos and one-string fiddle, cross-legged on a carpet - Bolan would exaggerate record sales, claim John Lennon wanted to produce them and insist he was the reincarnation of a Celtic bard.

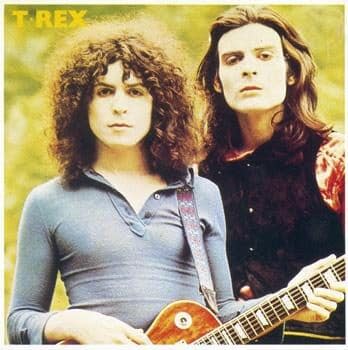

When a drug blasted Took stripped naked onstage and whipped himself bloody with his belt on tour in LA in 1969, he inadvertently changed rock music. Sacking him, Bolan took up with Mickey Finn, went electric and changed the band name to T Rex. Retaining his knack for outlandish characters and nursery rhyme poetry, he invented glam, a flamboyant post-psychedelia twist on 1950s rock’n’roll.

With his top hats, capes and glitter-dappled cheekbones Bolan was this new scene’s pixie prince, bringing catchy teenage pop frivolity back to a rock scene that had become increasingly serious in the hands of Hendrix, Lennon and Led Zeppelin.

Glam went off like a cannon. 1970’s Ride A White Swan turned Bolan into a bona fide teen idol feted by Bowie, The Beatles and Keith Moon, and sparked T Rextasy, aka 1970s Beatlemania. A dozen spangled T Rex classics dominated the charts – Get It On, Jeepster, Telegram Sam, Metal Guru, Children Of The Revolution – inspiring a plethora of stardusted imitators and ensuring Bolan’s place in rock history.

With his own myth confirmed, Bolan’s ego naturally exploded. “Any young man who’s swarmed over and told he’s the greatest thing on the planet, particularly by people like Lennon and McCartney and Ringo Starr, the ego is going to be massaged,” Roland says. “He’s going to give in to all the failings and faults, as a young man who has too much too soon would.”

Bolan bought a Rolls-Royce, began one-sided rivalries with Lennon and “one-hit wonder” David Bowie and edged dangerously close to his own ‘bigger than Jesus’ moment. “If God were to appear in my room,” he said in an interview, “I think he would dig me like crazy.”

Even when his sales were phenomenal – Electric Warrior was the best-selling album of 1971 – he’d pretend he’d sold double. Then came the rock star indulgences. His healthy vegetarian lifestyle gave way to copious brandies, rich foods and, eventually, cocaine. “It made him even bigger in his own mind,” his producer Tony Visconti told the Telegraph in 2002. “That's when the ugliness really started. He'd alienate the band with caustic statements: ‘you couldn't work with anyone else if you weren't with me’. It wasn't nice to watch.”

Another premonition. As a 17-year-old mod ace face, Bolan had told the Evening Standard, “the prospect of being a materialistic idol for four years does appeal”. Sure enough, by 1973 Bolan was declaring “glam rock is dead” and his chart positions fast declined. Unable to develop his style to keep pace with chameleonic pioneers like Bowie (over 10 albums with Visconti, Bolan used only seven chords), and unwilling to risk his glam pop success on an unfinished symphonic concept album The Children Of Rarn, he gained weight, left June and went to America with his new partner, singer Gloria Jones, to make plastic soul records in imitation of David Bowie’s Young Americans.

The albums tanked. “It was soul-destroying,” Roland argues. “To have that level of success and respect taken away and feel like you’re nobody, that’s what caused him to retreat into fantasy.”

Now Bolan was exaggerating his sales and celebrity to prop up his fading star. His press officer BP Fallon remembers being forced to concoct elaborate ploys to get journalists into Bolan’s home as if to avoid hordes of waiting fans that didn’t exist.

Yet, by 1976 he was on the verge of a comeback. Simplistic single I Love to Boogie might have made him look, in Roland’s eyes, “like the granddad of the Bay City Rollers… he was just knocking things off”, but it was a hit, and come 1977 he was ingratiating himself with the punk scene by touring his return-to-form album Dandy In The Underworld with The Damned.

“Marc was firing on all cylinders,” The Damned’s Captain Sensible told Classic Rock. “He’d got rid of his drug habit, he’d gone through his arrogant stage, he was almost humble.”

The success of I Love to Boogie had earned him his own Granada TV teatime programme, Marc; on September 14, 1977, he recorded his last edition of the show, featuring a guest appearance by his old rival David Bowie. The next day he drank heavily to celebrate the return of Jones and their two-year-old son from the US. That evening the couple ordered champagne at rock haunt the Speakeasy, then moved on to Morton’s to continue banging the late-night gong.

Jones played piano; Bolan professed undying love. But by 4am drink had the better of him, friends began drifting off and the couple headed home, with former nightclub singer Vicky Aram tagging behind to discuss musical projects. Bolan usually travelled by chauffeured Rolls, but his driver had the night off.

Though Jones was reportedly sober enough to drive she had reservations. “I kept saying, I don't want to drive this car,” she told me. “I should leave it here. But there was no parking, and I didn't want to get a ticket.”

Whether it was a loose wheel nut, weak pressure in one tyre or the car having been souped up by Pink Floyd’s speedfreak managers, Jones remembers losing control on a hump-backed bridge 45 minutes later. “When we made that turn, we weren't on the road, we were on the gravel,” she says. “The wheel came off on that hump… if we’d been in a larger car Marc would’ve survived.”

Aram was at the scene seconds later. “As I came over the bridge,” she told the Independent On Sunday, “I can still in my mind see, so clearly, a purple car which looked like a little beetle. It was upright and it was smoking and there was a tiny glimmer of light from the moon, the night was so still… I said 'we've got to get them out, this car might blow up'. I took my mother's rug from the back of my car and put it on the ground. Some of the fans are comforted by the fact he was laid on a nice lady's rug.”

By the following evening the sycamore tree on Barnes Common was a shrine of notes, messages and tearful fans. But Roland prefers Bolan’s legacy to be his memorial. He paints Bolan as the “archetypal young white rock god” and a mass of contradictions. An artist “acutely sensitive” yet arrogant to the point of self-delusion. Intuitively creative but obsessed with stardom to the detriment of his musicianship. An influential phenomenon yet “always chasing something”.

“He was his own worst enemy,” he says, “and just as he was about to live life to the full, it was taken away from him.”