It goes on and on, and on… The immortal power of Journey's Don't Stop Believin'

On September 22, 1980, at the end of an agreeable evening of mane-shaking soft-rock, Steve Perry walked off stage at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park and wiped his shoes.

“I said to the record executive – what’s with the spitting?” Journey’s erstwhile lead singer would recall of the band’s early adventures in the UK. “That means they love you? I don’t feel that.”

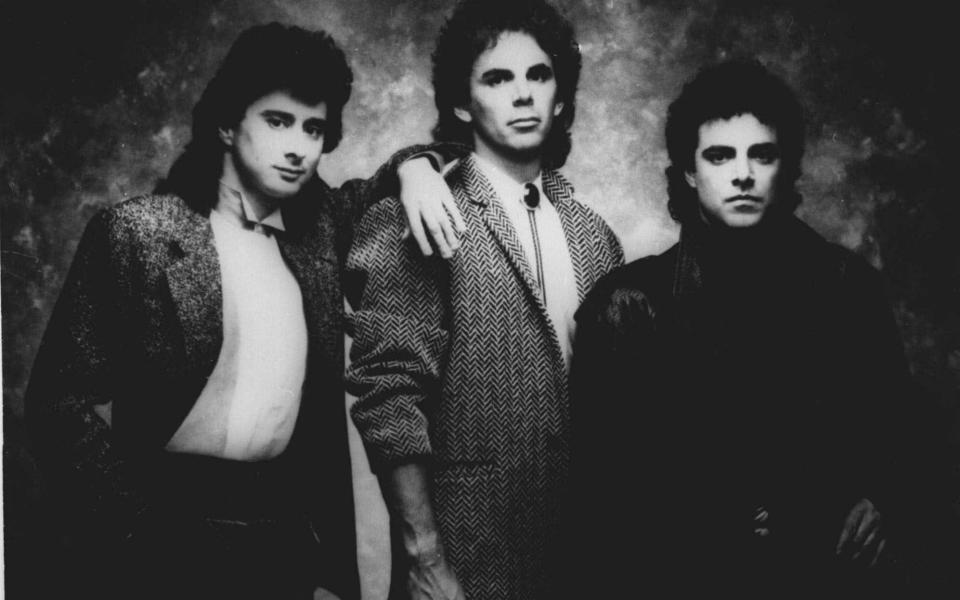

At the time, journey were the naffest of the naff. They had big riffs, even bigger hair, and the strong whiff of cheese. And they’d essentially invented the power ballad when Perry, a human foghorn with a gargantuan mullet, had joined three years previously.

They band were rock ’n’ roll minus the sex, the drugs, the danger (their manager once sacked an entire touring crew upon catching wind of their cocaine use). Jetting into the UK as punk was still burning bright, they stood out like a man in a bear-suit on a nudist beach.

Yet a little over 12 months after their gobby welcome in London, Perry and his bandmates would make rock history with one of the great feel-good anthems of the age – a track you couldn’t escape even if you wanted to. But then, who would want to escape Don’t Stop Believin’? It’s one of those songs that will never go out of fashion, largely because it was never in fashion to begin with. Much like seasonal sniffles and social media, it will be with us until the end of time.

Don’t Stop Believin’ is unstintingly optimistic. And its message that things will work out if only we keep the faith – “don’t stop believin’, hold on to the feelin’” – has never sounded more potent than now, as we face into the first and hopefully last, summer of Covid-19. Journey’s irresistible singalong is four minutes 11 seconds of staring into the darkness and seeing a light on the horizon.

Forty years ago, however, nobody involved with Journey had an inkling what Don’t Stop Believin’ would become. The band had enjoyed bigger hits, including Who’s Crying Now and Open Arms off the same 1981 album, Escape.

“That song got as much attention [as any other Journey track],” said Perry. “It wasn’t as if it got special attention. All the songs got the same amount of heartfelt emotion. Times just change.”

Nor did Don’t Stop Believin’ go very far towards salvaging their reputation with critics. As ever, they ruthlessly dismantled Escape. “A bunch of mediocre songs about people running away from things: perhaps this album,” said Melody Maker. “Escape is a triumph of professionalism, a veritable march of the well-versed schmaltz stirrers,” wrote Rolling Stone in the overblown style of the time. “Then again, when heroes are hard to find, the first thing you'll see are the showoffs.”

Only after the fact did Don’t Stop Believin’ take its place among rock’s greatest anthems. A drive-time staples for years, in 2007 the song gained a new lease of immortality when David Chase used it to bring down the shutters on the original of the prestige television species, The Sopranos.

Perry’s klaxon croon blares out during one of the most iconic final curtains in television history. At a family supper in a diner, complicated mobster Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) selects Don’t Stop Believin’ on a jukebox – having passed over Heart’s Who Will You Run To. The song strikes up, Tony’s family join him for onion rings, a bell chimes as someone enters the restaurant…and cut to black.

“They did not tell me it goes to black,” said Perry, who had withheld approval for the song’s use until three nights before The Sopranos finale went out. His concern was that Chase would pull the classic mobster movie flex of setting an uplifting melody to a tableaux of stylised violence.

“I kind of held out,” he said. “I didn’t want to see a Scorsese moment where everyone gets whacked. Scorsese would do that. He played these amazing songs and everyone gets mowed down.”

Sunday night,, when the episode was going to air, was fast approaching. And then, on Thursday, Chase’s office called. They shared with Perry the gist of how the final sequence unfolded – but glossed over the crucial detail of the screen suddenly cutting to black. “At least nobody got whacked,” Perry would say. “I love the way it was used.”

Don’t Stop Believin’s place in popular culture was cemented two years after the Sopranos, when it featured in the first episode of Ryan Murphy’s Glee. The acapella cover of the tune has been clicked on over 13 million times on YouTube – impressive until you consider Journey’s official video has notched up 98 million watches.

“Don’t Stop Believin’ ” was one of the first songs used,” Murphy would recall to Interview magazine. “Steve Perry was one of those guys right from the beginning who said, “Let’s try it”.”

In addition to being one of the great anthems, Don’t Stop Believin’ is famous/ notorious for its overbaked lyrics. The line “Born and raised in south Detroit” has caused particular bafflement. In Detroit, the southside of the city is referred to as Downtown. There is no “South Detroit”.

Called to task about this, Perry has stated that the imagery for the song came to him when Journey were in Detroit in May 1980, playing five nights on their Departure tour. Staring out of his hotel room window, he was struck by the night-time tableaux below.

“I was digging the idea of how the lights were facing down, so that you couldn’t see anything,” Perry told Vulture. “All of a sudden I’d see people walking out of the dark, and into the light. And the term ‘streetlight people’ came to me. So Detroit was very much in my consciousness when we started writing.”

“I ran the phonetics of east, west, and north, but nothing sounded as good or emotionally true to me as South Detroit. The syntax just sounded right. I fell in love with the line. It’s only been in the last few years that I’ve learned that there is no South Detroit. But it doesn’t matter.”

And if the lyrics have inspired millions it’s also hard to ignore their incredible hokiness. From “small-town girl’ to “midnight train”, cliche is piled atop cliche until the entire edifice threatens to collapse inwards creating a black hole of trite wordplay. Perhaps that’s why it worked so well on The Sopranos. There’s a weird tension between Chase’s unsentimental views of Tony’s life in crime and the moral debt that falls due and Journey’s clunking optimism.

It’s almost as if The Sopranos is showing us what a cliche looks like – before turning mobster movie stereotypes on their head with that famous cut to black. As it happens, the story of Journey’s rise and fall is at outsized as anything on The Sopranos. Perry was already well known on the LA rock scene, when, early in 1977, Journey’s manager Herbie Herbert sought him out. Perry would later insist Herbert be fired. And Herbert, for his part, would label Perry a “consummate assh*le”.

But that was all in the future when the manager drove out to meet Perry. He was living on the family farm in the San Joaquin Valley in Central California, having given up on music after the failure of his outfit Alien Project, which had fallen apart when bassist Richard Michaels died in a traffic accident.

Journey, led by guitarist Neal Schon, had ploughed a solitary furrow since starting out as an offshoot of Mexican-American jam band Santana. However, with their label, Columbia, threatening to drop them they accepted it was time to start making hits. Hence Herbert’s search for a vocalist and his visit to Perry.

His overblown style wasn’t universally beloved by his new bandmates. “Very Mary Poppins… so far removed from everything we had attempted to record,” was Schon’s assessment of the power ballads Journey were soon cranking out. “He thought he knew better about the songs,” said keyboardist Gregg Rolie. “He wanted to write them. You could see he was ambitious.”

“You would engage in a conversation with him and in the middle of a sentence he would tune out and walk away and start talking to somebody else,” agreed Ross Valory, the bass player whom Perry would have sacked in 1985. Journey re-hired him in 1995 only to fire him again last March. This time Perry publicly took his side.

It didn’t help that, on tour, he soon insisted on living apart from his bandmates. He would travel with his girlfriend, the rest of Journey slumming it in a tour-bus. “The joke,” Schon recalled “was that Elvis had left the building. He’d be done. We’d meet the fans.”

Perry acknowledged he could be difficult. “I really put my nose in places people would have rather I didn’t,” he told the makers of the 2001 VH1 Behind the Music documentary about Journey’s rise and fall. “Sometimes I wouldn’t lay down.”

Journey had regarded themselves as an underground affair, but Perry wanted to sell lots of records and play arenas. “I never really felt I was part of the band,” said the singer. “I always felt I was the outside guy.” He ultimately walked away from Journey twice. The first time was in 1987, suffering burnout in the wake of his mother’s death following a long illness. He did so all over again after Journey reformed in 1995 and released the hit LP, Trial By Fire.

With the comeback album a success, a sell-out tour was on the cards. Then Perry suffered a hip injury hiking in Hawaii. Diagnosed with a degenerative bone condition, he was told he required hip surgery to go on the road. He put off the operation and was finally confronted by his bandmates with an ultimatum: go under the knife or be replaced. He chose to leave. And so they hired Steve Augeri of Tall Stories (he would in turn be swapped out for Arnel Pineda, a Philippines Journey fan discovered on YouTube).

“They wanted me to make a decision on the surgery,” Perry told Rolling Stone. “I didn’t feel it was a group decision. Then I was told on the phone that they needed to know when I was gonna do it ’cause they had checked out some new singers.”

But it was another outsider who would furnish the group with their signature moment. In 1980, shortly after being gobbed into oblivion in London, original keyboardist Rolie left. With sessions for their next LP scheduled to begin shortly, it was decided to hire as his replacement Jonathan Cain, a Chicagoan who’d been doing well with London expat rockers The Babys.

Cain is today married to Paula White, a pastor and televangelist. She is chair of the evangelical advisory board to Donald Trump and delivered the “prayer of invocation” at his 2017 inauguration. A devout Christian, away from Journey he sidelines in religious rock. In 2017, several months after Trump’s swearing in, he visited the White House. Accompanied by Pineda and bassist Valory, Cain toured the Oval Office and posed for photographs with the President. He described it as “a historical chance to go and it wasn't political. I'm a history buff and was dying to see where all this history took place”.

All of that was news to Schon, who hadn’t been informed in advance and expressed his displeasure via Twitter. This led to speculation that Journey might split again, though they patched up their differences ahead of a co-headline tour with Def Leppard.

Let's be real shall we ? pic.twitter.com/15Q03Z3Ow4

— NEAL SCHON MUSIC (@NealSchonMusic) August 3, 2017

Cain and Perry weren’t necessarily close. However, they had one thing in common: a burning desire to be successful. To each Journey, represented a means to an end. The keyboardist also had a knack for maudlin ballads. Alas, in The Babys these dewy-eyed qualities were disapproved of and most of his ideas shot down. With Perry as ally, suddenly he had the means to share his weepy rockers with the world.

He co-wrote the three big hits on Escape. Open Arms and Who’s Crying Now were heart-on-all-the-sleeves weepies. With their soaring choruses, chiming keyboards and screeching guitar solos they went a long way towards creating the blueprint for the archetypal Eighties power ballad. Their viral essence lived on in everything from Bon Jovi’s Always to November Rain by Guns ’n’ Roses.

With Perry and Cain bonding creatively, if not personally, the sense was Journey were on the brink of something special. Yet there was still some dissatisfaction on the part of producers Kevin Elson and Mike Stone, the latter the engineer on Queen’s A Night at the Opera and co-producer of Freddie Mercury and co’s News of the World.

Escape required one final killer tune, it was felt. In a mild panic, Perry called Cain. Did he have any songs in the can?

“I go to his house the next day, the very next day, in his little flat, and then we got to write the lyrics,” Cain would remember. “I said, "What if it's like [John Mellencamp’s] Jack and Diane, you know? Kind of, “Just a small-town girl”. He goes, “Livin’ in a lonely world.””

It was heady stuff. But what they really needed was a chorus. Wracking his brains, Cain recalled a conversation he’d had with his father years previously. In the mid-Seventies Cain had left Chicago with dreams of making it in LA. It wasn’t happening – and then his dog almost died. Despairing he called his dad on a pay-phone.

“My dog got hit by a car, and I was in Hollywood, and I had to pay the vet bill. And luckily they saved her life,” Cain recalled to the Huffington Post “I had called him for some money, for another loan. And I hated calling my dad for a loan. I said, ‘Dad, should I just give up on this thing and come home? It seems like I might be pushing it back to Chicago.’ ‘No, no, don’t come home. Stick to your guns. Don’t stop believin’”

The phrase stuck with him. That same night, he jotted it down in his notebook of song ideas. And now, when he needed something magical to pull from a hat, there it was. Back in the studio, Journey got stuck in. Schon ripped through a solo. Perry laid down his vocal in two takes. For the chorus, all of Journey gathered around a microphone and howled their lungs out. Together, they delivered a yodel of optimism destined to live forever.

“The whole band is singing in one mic,” Cain would say. “Then Mike Stone mixes the heck out of it. ... And when we heard that record, me and Perry, we lost our mind.”

People have been losing their minds over Don’t Stop Believin’ ever since. The song has even been scientifically proven to have life-saving properties. Just ask California boating enthusiast Brad Warren, who was fishing off the coast in Hawaii in 2014 when a rogue wave capsized his boat.

Warren suffered a shattered leg and broken hip. With the sea crashing in, he felt the end approaching. “I tilted my head back to get another last breath of air and a swell pushed the boat, and I took a big gulp of water and started going down,” Warren said from his hospital bed. “It was scary.”

He and his companions bobbed in the ocean, alone except for each other for more than four hours. And then the 10-year-old son of his friend, clinging on beside Warren, heard something drifting from shore. Journey’s Don’t Stop Believin’, blaring out at a party. As Perry’s voice floated out across the water, the stricken men took heart and hung on. Not long afterwards they reached land, their journey helped by Journey.

Recovering afterwards Warren explained that Don’t Stop Believin’ was the universe’s way of telling him to keep going. “I thought that was the Lord saying, 'You will be fine”,” he said.