Gregory Gourdet of ‘Top Chef’: How I recovered from addiction and took back my health

I was a latecomer to the cooking game. By the time I went to culinary school, I had already been a pre-med student at NYU, a failed attempt to follow in my parents’ footsteps, and studied wildlife biology at the University of Montana, in Missoula. All I had to show for it was the knowledge that I didn’t want to do either. Well, that and a newfound commitment to recreational drug use. In high school, my first dalliance with alcohol — 40s of Olde English snuck into a Manhattan movie theater for a showing of "New Jack City" — produced an electrifying sense of lightness, a bodily freedom I had never felt before. I chased that freedom for years, sneaking slugs of my parents’ Barbancourt straight from the bottle after they had gone to bed, then graduating to smoking weed and dropping acid to snorting ketamine, small-town meth, and cocaine and cocaine.

When I wasn’t high, I was cooking. At first, I cooked with my roommate, Dave, in the tiny bungalow we rented, feeding ourselves for the first time with scrambled eggs and treating the inevitable comedowns with fettuccine Alfredo, scalloped potatoes and heaps of other cheap, fatty carbs. Later, once I realized that making food and feeding others gave me pleasure, I cooked at a bookstore slash vegetarian deli, then at a cafe in town where the chef saw potential in my dishwashing and prep skills, letting me griddle veggie burgers during lulls in service. He suggested I consider culinary school.

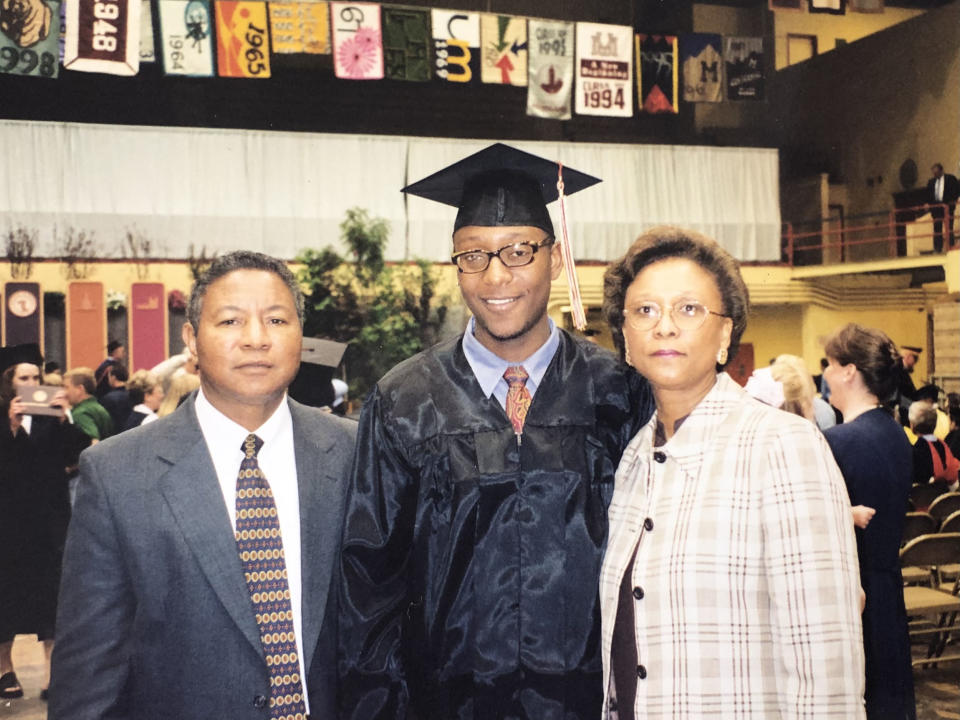

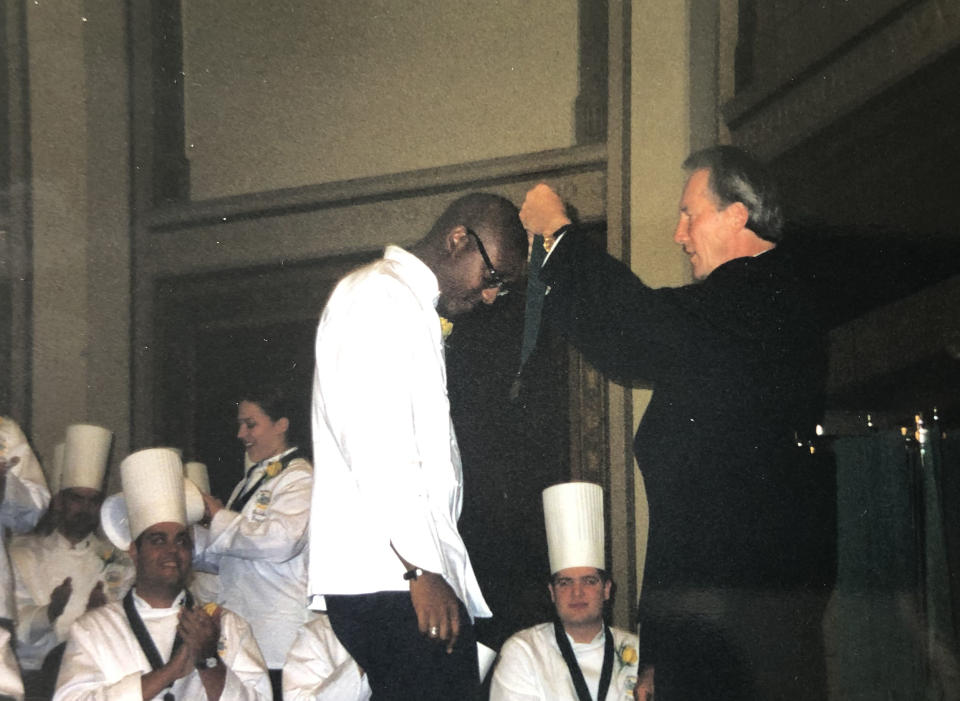

Endlessly supportive, my parents agreed to help, as long as I cobbled together enough credits for a degree from the U of M. Once I did, I set off for the Culinary Institute of America. There, for the first time, I inhaled my classes, but still, I kept partying.

When I graduated, I lucked out and got a job working for Jean-Georges Vongerichten at his four-star flagship, where I quickly climbed the ranks and, at 29, I was running Jean-Georges’s modern Chinese restaurant, 66, creating dishes and menus for one of the best chefs in the world. But as my career accelerated, so did my habit. Cooking and drugs provided a similar thrill because they were both a tightrope walk — at the end was elation, but below were flames and failure in the kitchen and death in the bottle or bag.

Soon I was drinking at work and freebasing at night. Inevitably, I got fired. I tried rehab and would stop drinking for weeks, only to relapse spectacularly, as I did on a fateful New Year’s even when after twelve hours of drinking, I decided to drive home. Somehow, I escaped the shell of bent metal and broken glass with just a small scratch above my left eye. I was lucky that I spent the night in jail and not the ICU. In a movie about an addict, this would be the moment everything changed, when the protagonist checks himself into rehab and emerges a new man. But this isn’t a movie. It took another year for me to quit drinking and doing drugs.

When I finally got sober, I took stock of the years I’d spent battering my body and decided on a revolutionary course of action — to care for it instead. And like I once did with partying, I went all in. I did yoga, I became a gym rat, I got way into CrossFit and I ran until I had done fifty marathons and ultramarathons, including two fifty-mile races, several of which were up mountains.

I also changed my diet. My CrossFit coach suggested I try a Paleo diet. As I purged my fridge and pantry according to the Paleo dictates, I felt good about what went and what stayed. As I dug into this new lifestyle, I liked what I was eating. I also liked how I felt. And while it was Paleo that started me down this path, this way of eating is at the core of so many of the best eating regimens, old and new, from the Mediterranean diet to Whole30: whole, natural foods, plenty of good fats, nutrient-rich carbs, and meat and seafood raised and harvested by thoughtful farmers and fishers. It’s a durable consensus that I like to think of as modern health — not a crash diet but a sustainable lifestyle, not a calorie-counting scheme that equates skinny with healthy but a way of eating that has the health of your body in mind. It’s about curtailing the bad stuff and going all in on the good.

I still eat Paleo, more or less. I’m not Draconian about it. I can’t pass up my mom’s rice and beans (that and her chicken in creole sauce would be my pick for my last supper) and when I’m traveling, I can’t not have bites of buttery tortelli in Tuscany, sample chewy ramen in Tokyo, or nibble my way through half the case at a Parisian patisserie. The experience of learning and tasting food, particularly at its culinary source, is too important for me, as a chef, to renounce altogether. So is accepting the gesture of hospitality feeding people embodies.

Mom's Haitian Meatloaf on a Sandwich by Gregory Gourdet

With that in mind, the recipes in my new cookbook, "Everyone's Table," are the food I cook for friends and for myself. Unless I told you, you probably wouldn’t notice that all two hundred recipes are free of gluten, dairy, soy, refined sugar and legumes. You wouldn’t notice that I made them Paleo-friendly, and even more important, that I designed them to focus on superfoods — ingredients with the highest nutrient density, the best fats and the most minerals, vitamins and antioxidants. You wouldn’t notice — and that’s the point. All you’d see is food you want to make.

From the book EVERYONE’S TABLE by Gregory Gourdet and JJ Goode. Copyright ? 2021 by Gregory Gourdet and JJ Goode. Published by Harper Wave, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Related: