The Guts and Glory of Carolyn Pfeiffer

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

When Carolyn Pfeiffer arrived in New York City in the late 1950s, she was a tomboy from rural North Carolina who was curious about the world. Before long, she booked a one-way trip to England, and her ensuing adventures unfolded against the thrilling backdrop of European cinema in the 1960s, where she was a fly on the wall for some of the seminal movies of the time, like 8 ?, The Leopard, and Doctor Zhivago. In her new memoir, Chasing the Panther: Adventures and Misadventures of a Cinematic Life, Pfeiffer evokes the culture of European cinema with affection, but without sentimentality. The book is ripe with glittery stars such as Claudia Cardinale, Alain Delon, and Omar Sharif. There’s old Hollywood (Burt Lancaster), new Hollywood (Barbra Streisand), and the British Invasion (The Beatles). There's plenty of fun stuff, too, like smoking weed with director Blake Edwards during the filming of The Pink Panther.

As an executive at Alive Films in the 1980s, Pfeiffer went on to produce or distribute indie hits such as Kiss of the Spider Woman, Choose Me, and Stop Making Sense. But this book remains focused on her early years. It’s a classic coming-of-age story, with Pfeiffer devoting as much time to her string of lovers and the wonders of European culture as she does to the minutia of filmmaking. It’s through her deeply-felt descriptions of young love, of being a foreigner in Europe, of living and experimenting and learning about oneself, that the book connects.

During her first visit to Eygpt with Sharif, for whom she worked for several years, Pfeiffer encountered the Great Pyramids on horseback at night. Though she was far from the North Carolina pastures where she grew up, Pfeiffer let it fly, her horse galloping as she approached the shadow of the pyramid. It’s a soaring, lyrical moment, and Pfeiffer—and her co-author Gregory Collins—puts us right there. Pfeiffer has a no-nonsense style; she’s a straight-shooter, but also a natural storyteller. She’s lived a charmed life, but one, she cautions, where “terrible things can happen at any time.”

Pfeiffer Zoomed with Esquire from her home in Marfa, Texas. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: How old were you when you first yearned to travel?

Carolyn Pfeiffer: Young. I was born in Washington D.C. and my parents moved to Madison, North Carolina, when I was six years old. Being an outsider—they called me Yankee—might have been part of that, but I think I was just drawn to other things.

That remains a theme for you in your twenties, as you describe in this book—being an outsider in London, in Rome, in Paris.

But with a difference. I was never an American in Paris or an American in Rome. I immediately gravitated to the culture of those places, learned the language as best I could, and worked. I didn’t really think of myself as an outsider. I was always a foreigner, but I was really comfortable in these cultures.

$28.24

amazon.com

People seemed to take a liking to you. Like the family of your boyfriend Masolino d’Amico—especially his mother, Suso Cecchi d’Amico, a pioneering screenwriter whose work includes neo-realist masterpieces such as Bicycle Thieves and Rome, Open City.

Suso is the matriarch of Italian cinema. There’s nobody that could duplicate her career and the contributions she made as a screenwriter. She was born in Florence at a time when women didn’t work, of course. After World War II, her husband developed pulmonary disease and went to Switzerland to cure—for a long time. Suso was left with two small children and tried to figure out how to support them. She was recommended to do this one screenplay, and that was the beginning of her career. She was very droll. Very calm and thoughtful about everything. For some reason, she took me under her wing, and that lasted until she died. She was my mentor in many ways, but she never would have said that.

What do you think she saw in you?

I don’t know. I think maybe an independence. And a kind of straight-forwardness.

And she helped get you your first work in the movie business. Was that ever something you dreamed about?

No. I found myself in the film business because I needed a job. I got a job teaching English through the d’Amicos, because Hollywood was coming. That’s what they used to say: Hollywood is coming. The Americans were starting to make films in Europe. Everyone needed to learn English.

And then you had the good fortune to meet Claudia Cardinale, a rising young star in Italian cinema.

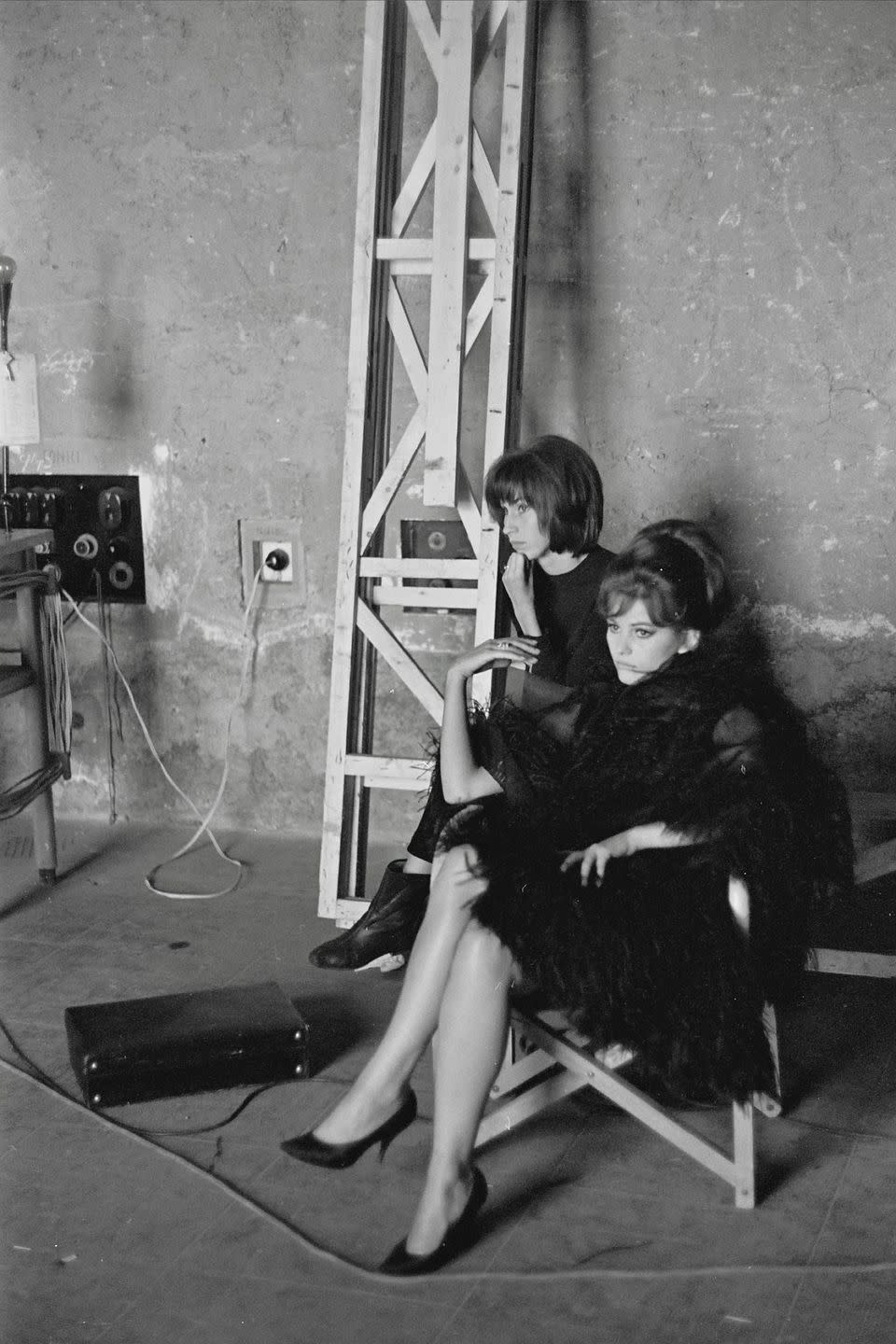

Originally, I was hired to teach Claudia English. We got along really well; she didn’t have a secretary, and so I took that on. Franco Cristaldi was a well-known Italian producer. Claudia was under contract to him. She did a few French films and Italian films, and then bam: she got 8 ?, The Leopard, and The Pink Panther in a row, all three of which live on in the annals of movie history. I obviously knew these were exceptionally gifted people—but you don’t have any idea what the duration of these things will be. You’re too young to remember to save anything, for God’s sake. I should have saved the call sheets. Who knew?

I loved how you evoked Fellini’s working method and what a towering figure he was at the time of 8 ?; also, how he and Visconti, who directed The Leopard, were vying to be the top dog of Italian cinema. One thing that stands out about your experience is that Cristaldi made it your duty to never allow Claudia to be alone with Fellini.

Fellini, like Visconti, these were giant people. I can’t fully explain to you their aura, their comportment, their reputation. It was otherworldly. But even though Fellini was devoted to Giulietta, his wife, it was well known that he loved round women, and Claudia was a very beautiful woman. These are Italian guys. Cristaldi knew Italian guys, so he was really nervous. I don’t think he was nervous about her having a one-night stand with Fellini, but he was nervous that somehow Fellini would try to seduce Claudia. Fellini was a very seductive man and she was his muse in the film. Boundaries are crossed when you are in the world of making a film. It’s a world unto itself. And people become very much a part of that world and do forget what’s outside that world.

How did you and Claudia get along?

Claudia, in all the time that I worked for her, was a very straight-up gal. Her family moved from Tunis to Italy with her. At the age of 20, she was the provider for her family. She had this weight on her. Also, it turned out that she and Cristaldi were lovers. It was never discussed. Never open, though everyone knew. He was married. Eventually he got divorced, and he and Claudia got married. And then they got divorced.

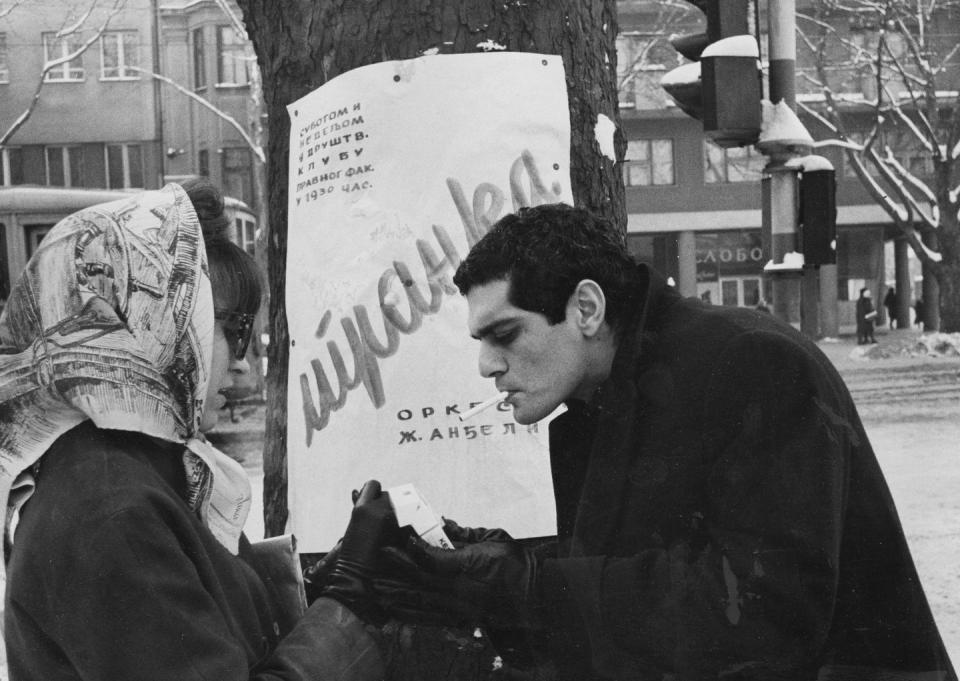

You talk about the relationship between Claudia and Cristaldi, and how she was beholden to his business decisions. But a few years later when you worked with Omar Sharif, a male star, you discovered that he didn’t have much contractural freedom either.

They were put under contract. In order to do Lawrence of Arabia, Omar signed a five-or six picture deal with producer Sam Spiegel. He didn’t have a choice in his roles. Any role Sam wanted him to do, Omar was legally bound to do it. It took years for William Morris, Omar’s agent, to get him out of that deal. When I was working for Omar, we’d go from film-to-film-to-film almost living off our per diems. He would get really good per diems, and because I was part of his package, I’d get a decent per diem. Of course, the production would pay for housing. We’d be in fabulous first-class hotels with cars and drivers, and all the accoutrements of being really, really rich, but there was no money.

In addition to your long relationship with Omar Sharif, you also had encounters with Barbra Streisand and the Beatles where you saw the frightening side of fame.

I was with the Beatles in the south of France. I kept saying to Maureen, who was Ringo’s wife at the time, and pretty experienced, “Whatever you do, don’t let go of him. As long as you hold onto him, you’ll be okay.” She was pregnant and got punched in the stomach, not deliberately, by someone trying to get closer. It's really scary. I was thinking about Meghan and Prince Harry, and how they talked about trembling in the taxicab. I completely understand that. I’ve been in those situations where the mob is in control, and you really don’t know whether you’re going to be hurt. The best thing you can do is stay as close as you can to the person of fame, because that's the person who will be protected. I think because of these kinds of things, there's a language between famous people that civilians aren’t even aware of.

Late in the book, you write that “terrible things can happen at any time.” That’s certainly true in your story, especially when you write about being raped by one of Alain Delon’s bodyguards. The way you describe it, there’s this awful inevitability about it, because he was hawking you before you consented to go out with him.

We had to change the name of the bodyguard for legal reasons. I remember well what his real name is. There’s a thing with women of the time. We made constant excuses for men, and men made constant excuses for themselves. One thing for sure, I did not want to be defined by this guy. It really was before a time where it would have even occurred to me to protest or take it to the police. I never told Alain, who would have been furious. But it stayed with me my whole life. It never became less painful. It doesn’t go away—down there, it’s buried. It’s part of you.

As someone who worked closely with movie stars, you write with discretion and sensitivity about their private lives. I came away with a sense of all the stories you didn’t tell, which makes the ones you do tell even more potent. One was about Fellini, who grabbed your butt on the set of 8 ? in front of a group of people to publicly humiliate you, because he was frustrated that you wouldn’t let him be alone with Cardinale. The other involved Sean Connery.

I wasn’t revealing details about my clients or other people. Both of those are things that happened to me, which I felt was allowable. I mean, both men stepped over the line, man. To me, it was so shocking that someone as revered as Fellini would resort to such a low tactic. I didn’t include it in the book to show people he was a bad guy, but it’s my story and it happened to me, and it affected me, and here I am 60 years later still talking about it because it was over the line. It doesn’t matter that he was a genius and amazing to watch work.

Then there's also a brief description of a scene with Sean Connery, who molested you in a restaurant by shoving his hand up your skirt several times. You don’t spend a long time on it, but you don’t ignore it either.

Sean, the thing that was most egregious, was that his wife, Diane, was sitting on the other side of me. I mean, I loved James Bond movies, but there was no way I was interested in having Sean Connery grope me. I’m sure I wasn’t even his type. I’m not even sure what his fucking problem was. But I was there with one of his close friends as a date, and I was sitting next to his wife. I mean, figure that out. I mean, what on earth would motivate a man to do something … like that.

That is one’s life and one’s life is filled with things like that. So you decide whether you’re going to talk about these things or not, and whether they are of interest. I certainly wasn’t out to hurt anybody in my book—I don’t think I did. Much more difficult for me was writing about the relationships I had with men that I loved and who loved me. Break-ups and things like that. Those were really hard for me.

I can only imagine how challenging it was to write about the tragic death of your first daughter, Lola.

My pregnancy was unintended. When I discovered I was pregnant, I was startled, but then as I processed it, I thought, I can do this. I am financially self-sufficient. I have friends and something of a support system. I really wanted this baby. It was powerful. At the time, it was very unusual to have a child out of wedlock and I was afraid of losing clients, so I did not say anything to most people until I could no longer hide it. I had a happy pregnancy and an easy birth. The moment when you see your child is beyond joyful. I was pretty much English by this time, in my habits and routines. Lola and I had a simple, happy life. Then one evening, she was fussy. I called the doctor. He said it didn’t sound serious, to give her Tylenol and we would see how she was in the morning. I had to go to the studio very early and she was sleeping, but the nanny was there.

Then I got the call and raced to the hospital where they had taken her. Lola did not survive. A virus had gone to her brain. Meningitis. The pain of losing a child is unbearable. In the almost year that followed, I kept working and tried to live life as before, but I could not pull out from the deep sadness. I started to think I needed to return to America. I'd had good working relationships with Robert Altman and Shep Gordon, who both invited me to join their companies. It seemed that with Shep and Alive Films, there would be a real chance to build something, so I returned home.

Okay, one last thing: one of my favorite parts of the book is when Suso d’Amico talks about finding your genius. That we all have an inner genius of some kind.

I’m not as eloquent as Suso but yes, to simplify: everyone has a gift of some kind of—Suso called it genius. And you have to discover your internal gift—or genius—and with that gift go out into the world. Many people never really understand or recognize their gift, but everyone has it.

What’s your genius?

I think it’s the ability to keep going and always want to keep going. I love to problem-solve and I love to collaborate; those are qualities that make a good producer. One’s genius is not specially a career you choose, however, but something inside you.

You Might Also Like