Hannie Caulder: Raquel Welch’s bloody, controversial (and British) revenge Western

Last month, an elegant elderly woman caused a paparazzi frenzy as she left an auction house in Beverly Hills. It was Raquel Welch, now 81 and photographed in public for the first time in two years, looking – one tabloid noted – “casual in a white top, black pants and platform wedges, paired with a straw hat and stylish eyeglasses”.

This was still recognisably the bombshell who starred in Fantastic Voyage (1966), One Million Years BC (1966) and Myra Breckinridge (1970). And her re-emergence also coincides with the 50th anniversary, early next month, of what many regard as her most remarkable film – the now-forgotten, yet influential revenge Western, Hannie Caulder.

The making of this violent potboiler was a whole saga in itself, a tale of bitter feuds and bust-ups. Although shot in Spain, Hannie Caulder was described as “a British Western”. The film, which had its premiere in London on November 8 1971, was funded by Tigon British Film Productions, it was edited and mastered in Twickenham and it also starred Swindon’s own Diana Dors as a Mexican brothel owner. The movie also came with a bizarre publicity campaign featuring Welch kicking footballs while dressed in a Chelsea football kit.

Welch, an international sex symbol after donning the famous skimpy fur bikini in One Million Years BC, was 30 when she began filming Hannie Caulder in January 1971. She said she accepted the role of the retribution-seeking “frontier gal” because, at the time, she was “gravitating towards physically active roles”. Hannie Caulder is the story of a woman, living at a remote ranch, whose husband is murdered by three outlaw bank-robbers – played by Ernest Borgnine, Strother Martin and Jack Elam – who then take turns sexually assaulting her. Although the film earned only an R certificate (restricted, with under-17 viewers requiring an accompanying adult), the scene is disturbing and abhorrent. “Look what we’ve got for supper!” exclaims Martin’s character Rufus, the stupidest of the three Clemens brothers.

Traumatic memories of that rape drive the lead character’s desire for bloody payback. Welch’s character relives the assault in lurid flashbacks later in the film, and when she encounters the gang again, they boast of having had “a good old time”, threatening to inflict the same violence on her again. In his November 1971 review, film critic Derek Malcolm wrote about what he called a “gang-bang” scene and discussed the problematic nature of treating the predators comically, referring to them as a “Wild West version of The Three Stooges”.

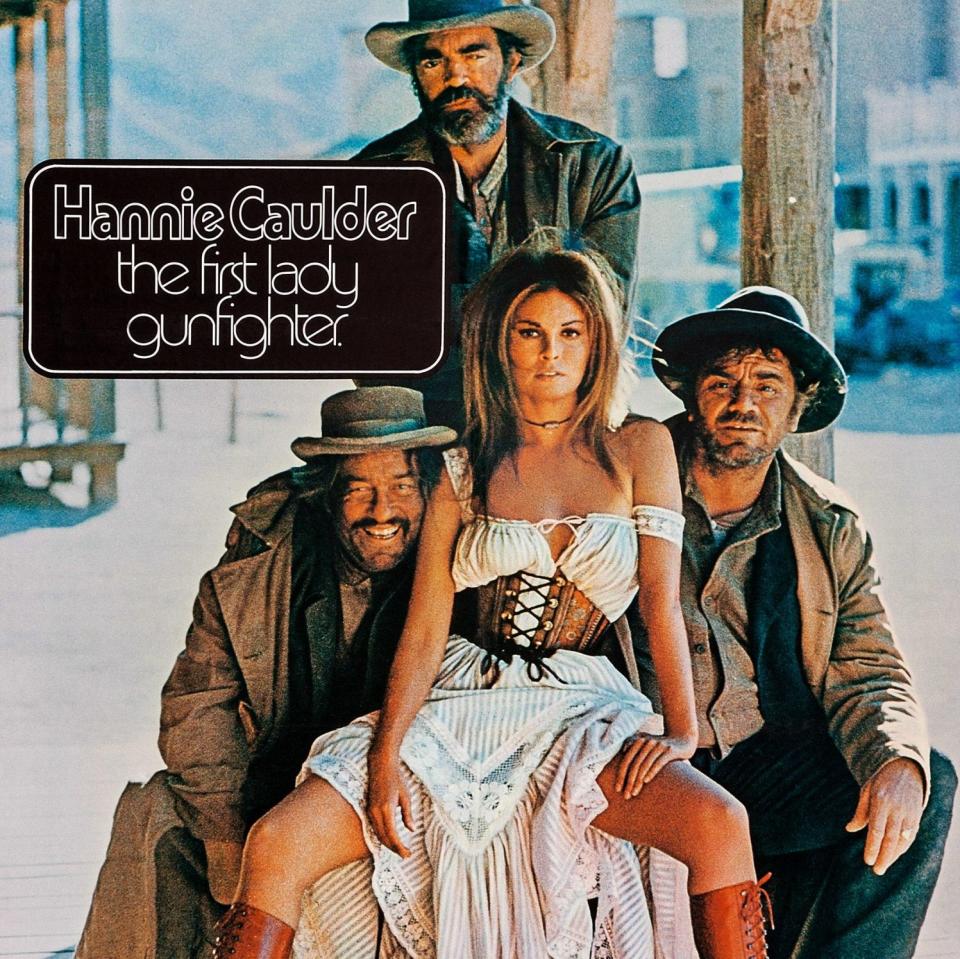

Although the promotional posters or Hannie Caulder emphasised the theme of vengeance, referring to her as “The First Lady Gunfighter!” and a woman with “a notch on her gun for every man she got”, the marketing campaign did little to reflect the gravity and viciousness of the crime that drives the plot. One poster, used throughout the world, showed Welch posing in a white dress and high-heeled leather boots, her shoulders and cleavage exposed, legs spread wide, posing with the three rapists. Martin is grinning with a suggestive, leering smile on his face.

Nor did the gravity of sexual violence seem wholly apparent to Borgnine, whose character also beats Caulder as he rapes her. In 2009, the 92-year-old gave an interview to The Scotsman in which he looked back on his career highs and lows; he boasted that one of the highlights of his life as an actor was the time “I had my way with Raquel Welch”.

It’s possible that one reason playing such a strong-willed character appealed to the actress was because the film dealt with the subjects of male aggression and violence towards women, something with which she had grown up as a child in Chicago. Welch, who was born as Jo-Raquel Tejada, described her Bolivian-born father Armando as a “dictator” and “terrifying”. In her 2010 autobiography, Beyond the Cleavage, she wrote movingly about his “anger”, and how he used to “lash out” at Welch’s mother, Josephine.

One time, after complaining about a casserole she had made, he picked up a glass of milk “and threw it right in her face”. Welch recalled how she sprung to her mother’s defence. “I screamed and picked up the poker from the fireplace and turned toward him, gripping it with both hands. I was pitted against him now. ‘If you ever, ever do anything to hurt Mom again, I swear, I’ll kill you!’ I said, shaking with emotion.”

Her first marriage to high-school boyfriend James Welch, with whom she had children Damon and Tahnee, ended in 1964, and she married Patrick Curtis in Paris three years later. Curtis, who was a nephew of Billy Wilder, took a controlling interest in her career, and the idea of playing a vigilante came from him. Curtis took the script for Hannie Caulder, based on an original story by Peter Cooper, to American director Burt Kennedy, who had written scripts for John Wayne. “It wasn’t a very good script,” Kennedy would later remark; he went to Madrid for a couple of months and together with David Haft did a complete rewrite.

Kennedy was responsible for selecting Borgnine, Martin and Elam (who had acted in Kennedy’s 1969 Western, Support Your Local Sheriff!) and said he wanted a “comedy” element to the Clemens siblings along with a script that showed off Hannie’s feisty character. He gave Welch’s character some memorable lines, particularly when she stands her ground with a leering lawman. When Sheriff Lee (Luis Barbook) slaps her behind and tells her that her bottom is back, she fires back, “And so’s your chin.” When the sheriff upbraids her for killing a man and says, “Damn it, woman, you didn’t have to cut him in half, did ya?”, she replies, “Both halves match, don’t they?”

Welch could be quick with a retort in real life. During a promotional tour for Hannie Caulder in 1972, she appeared on Michael Parkinson’s chat show. When he tried flirting with her and made a crass joke about wishing she would cut him in half, she retorted, “Are you one of those hit-me-again types?” Hannie’s quick wit, as much as her speed on the draw, became a reason the character was hailed as a feminist role-model. When the movie was screened by BBC One in 1997, it was introduced with the description “Girl Power, way out West”.

That said, the filmmakers were keen to exploit Welch’s sex symbol status. The film includes a gratuitous half-naked bathing scene and lingering crotch shots, and Welch spends the first quarter of the film wearing a scanty poncho. Although life as a pin-up brought her fame and riches, Welch complained about being objectified. She later admitted that she had undergone psychotherapy about her body issues and suffered a tremendous “loss of self” about being judged on her body alone. She described beauty as being “like a crutch” and likened being a sex symbol to living like a convict, “locked in this image… I couldn’t get out.”

Hannie Caulder was filmed in Spain in Madrid, the Andalucían city of Almería, a beach on the Costa del Sol and the rugged terrain of the Tabernas Desert. Kennedy later told the writer C Courtney Joyner, for the latter’s book The Westerners, that there were lots of difficulties on the set, some created by money-men “who never came up with the money”. In one heated row, he refused to allow an executive from Tigon to take a negative of the film back to London in a suitcase. The journalist Robert E Kee, making a set-visit for Copley News Service, filed a story headlined ‘Raquel’s Newest Like a Circus’, in which he detailed the complications on the set, including the “loud and strong” rows, the abrupt resignation of an Italian photographer and the fall-out after a blonde girl was banished from the set for an unspecified infraction.

Along with minor mishaps – Culp was poisoned by a sea urchin during a recreational swim – there was also a tragedy when Rodd Redwing, hired as a technical advisor to teach Culp and Welch how to draw their guns quickly, suffered a heart attack while returning to America from Spain. He died shortly after the plane landed in Los Angeles.

In The Westerners, Kennedy also revealed that Welch was involved in a ferocious punch-up with one of the crew. “Raquel travelled in a brown four-door Mercedes,” he recalled. “She shows up for work late – or at least the first assistant said she was – so as soon as he said, ‘You’re late’, she hit him. Right on the jaw, like John Wayne, and down he went!

“I just turned round and walked back into the saloon. I thought, ‘I want no part of this.’ Now, the crew were so upset, they not only quit, they said, ‘You’ve got to get out of Spain, we don’t want this company here.’ So, the head of crew finally went to this guy – his name was Diego Santierre – and said, ‘Look, if Raquel comes to you and apologises, and you accept it, they can get back to work.’ Diego came to me and said, ‘What should I do?’ And I said, ‘You’ll be famous by tomorrow because of what Raquel did.’

“Raquel gave a speech in Spanish about how she was a warm-blooded woman, just like the Latins or something, and they loved it, and they applauded, and they went back to work. Eddie Scaife, our British cameraman, said to me: ‘Well, the best man apologised for screwing the bride, and the wedding is back on.’”

Kee also reported that some of the crew made disparaging remarks about Welch’s acting abilities. He printed one insult that claimed “Ernie Borgnine’s a better actor in a bathtub than Raquel Welch is out of one.” Her performance attracted some harsh criticism from the press; along with Malcolm’s comment that “as Hannie, Welch makes a pretty dotty sex symbol and a very wooden actress”, she was also labelled “plain ludicrous” (Vanity Fair). One of the most inappropriate reviews was from Time magazine critic Jay Cocks, who wrote: “Miss Welch’s acting ability is greatly overshadowed by her endowments. Consequently, her thrashings and grimacings while being assaulted assume an air of piquant comedy.”

Matters on set were made worse by divisions among the actors. According to Kee, the group was “split into two camps”. He described attending a post-shoot evening meal: “Borgnine, Elam, Martin and Kennedy dined quietly together and played Liar’s Poker continually, with good-natured ribbing, and Miss Welch, surrounded by publicity man, nursemaid (yes, the sex queen brought her child to the location) and trendy English photographer Terry O’Neill held court at another table.”

O’Neill took some of the most memorable photographs of Welch during her career – including the one in which she wore a Stars-and-Stripes bikini, Stetson hat and cowboy boots in a promotional portrait for Myra Breckinridge, and ‘Raquel Welch on the Cross’, the crucifixion photograph that was deemed too controversial to be published at the time. The chirpy Londoner persuaded Welch to get involved in a series of publicity stunts in which the gunslinger wore a replica Chelsea Football Club shirt, the team he supported.

During filming in Spain, O’Neill persuaded Welch to wear the number nine shirt worn by striker Peter Osgood, while she also sported a holster and gun around her waist. In one photograph, she is even pictured kicking a football. “We were shooting in the middle of the desert, but I managed to convince Raquel to put on a Chelsea strip for a kickabout on the Wild West set,” recalled O’Neill.

Some 20 months later, he helped arrange for the actress to visit Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge ground, where she watched a 1-1 draw with Leicester. That football trip remains one of the oddest Hollywood-football interactions. On Saturday 11 November 1972, Welch was chaperoned by the bearded, middle-aged television host Jimmy Hill. and she then watched the game from the stands. The whole afternoon was replete with the sexism of the times. In his memoir, Hill joked that he was “aware of no bra – on Raquel, of course”, and added the (far-fetched) claim that during the taxi journey back to the Savoy Hotel, “Miss Welch looks at me and says, ‘Jim, how would you like to handle me in Europe?’”

Osgood himself, writing in his 2002 autobiography Ossie: King of Stamford Bridge, remembered that Welch endured “a cacophony of wolf-whistles and cries of ‘Get ’em off!’ from the crowd”. He added that “she was very beautiful, and wearing tight trousers, and all the lads were looking, thinking, ‘How the hell did she get into those?’” For her part, Welch said she’d enjoyed her trip to a football match, adding “women should be here watching all these lovely men do wonderful athletic things”. (Welch was reportedly later photographed wearing a T-shirt that said, “I scored with Peter Osgood”.)

By the time of her visit to Stamford Bridge, Welch was single again, having divorced Curtis in January 1972, after claiming he had “turned into a Svengali – I felt I was being manipulated”. The end of the marriage also meant the end of Curtwell Enterprises, a production company Curtis had set up with Welch, one that combined their names. Welch would go on to have two more husbands (André Weinfeld, 1980–1990, and Richard Palmer, 1999–2010), later commenting that she did not think she was “any good at marriage”.

Although Welch never realised her true dream of making it as a big-band singer – she said she would like to record an album with Randy Newman – she went on to make 18 films after Hannie Caulder, which ranged from her Golden Globe-winning performance in 1973’s The Three Musketeers to her Golden Raspberry-nominated part in 1998’s Chairman of the Board.

Hannie Caulder did better box-office trade in Britain than America, and there was sufficient interest for British publishers Pinnacle Books to bring out a novelisation of the film, written by William Terry. (The film would be re-released on Blu-Ray in 2009.) It continues to resonate among Western fans, too, and in 2016 there was a loose remake called Jane Got a Gun, starring Natalie Portman. Most significantly, Hannie Caulder had a huge influence on Quentin Tarantino. In August 2003, when the director was talking to the Japanese media during a press junket for Kill Bill: Volume 1, he cited Welch’s movie as a key inspiration, especially the interaction between her character and Robert Culp’s bounty hunter, Thomas Luther Price.

There are many other footnotes to Hannie Caulder. The Spaniard Paco de Lucía, the virtuoso flamenco guitarist who played with jazz legend Chick Corea, appears as a Mexican musician, while the Golden Globe-winning actor Stephen Boyd, who had worked with Welch on the science-fiction movie The Fantastic Voyage (1966), played a mysterious, threatening stranger dressed as a preacher.

“In Hollywood, if an actor plays a tiny part in a film just because he fancies the role, everyone thinks he’s on the skids,” said Boyd, quoted in Joe Cushnan’s biography, Stephen Boyd: From Belfast to Hollywood (2013). “I was offered such a part in Hannie Caulder. I said ‘yes’, and everyone thought I was mad. So I played it under the name Nephets Dyob, which is my name spelled backwards.”

The two most famous guest stars on Hannie Caulder, however, were Christopher Lee, who visibly enjoyed performing in his first Western, playing a gunsmith called Bailey, and Diana Dors. “Christopher Lee really took to the Spanish locations. I think he enjoyed being in a Western rather than being Dracula again,” said Kennedy. Dors, meanwhile, credited simply as ‘Madame’, plays a Mexican bordello owner. Many of her lines were cut from the final 85-minute movie, but the 39-year-old did get one small scene with Welch, in which she confronts the avenger on the stairs of the brothel and says, “Hey, I don’t remember hiring you?” (Incidentally, Dors’s role as Madame came four decades before it was revealed that she staged her own orgies at her Orchard Manor home in Sunningdale, sex parties at which she would secretly film celebrities having sex with young starlets.)

Dors is just one of the reasons why Hannie Caulder is such a mixed bag. Some of the best moments involve Hannie and Culp’s bounty hunter: when Price warns Hannie that teaching her how to use a gun may end with having her “a-- blown off”, she retorts, “It’s my a--”. But the film also has plenty of defects. The copious fake blood is unconvincing, the verbal horseplay between the Clemens brothers is tedious and unfunny, and some scenes, such as the gun battle with mystery bandidos at the gunsmith’s beach home, make no sense.

Welch once said that she worried that “Hollywood gossip” had made it a simple “reflex action” for people to think of her as nothing more than “a silicone Barbie doll”. But her role as Hannie Caulder, for all its flaws, is part of why she made a worthwhile contribution to cinema history. Just ask Quentin Tarantino.