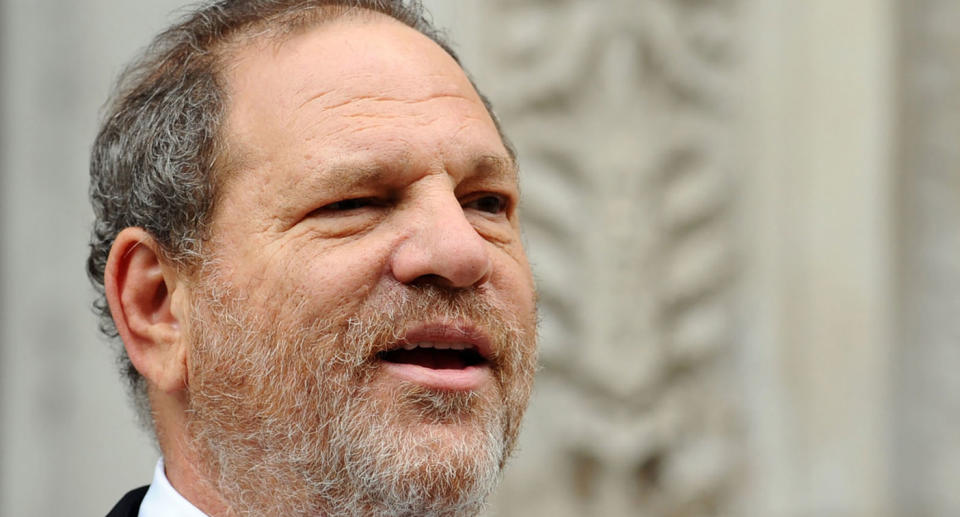

Harvey Weinstein sex harassment allegations: What led to the decades-long code of silence?

An explosive New York Times story detailed decades of sexual harassment accusations against Hollywood titan Harvey Weinstein on Thursday, prompting the film producer’s lawyers to announce their plans to sue the newspaper for defamation within two hours of its publication.

The article raises a slew of questions about Weinstein’s alleged behavior over the years — from repeatedly summoning actresses (including Ashley Judd) to his hotel rooms while wearing next to nothing and requesting massages, to the apologetic statement Weinstein released to the Times on Thursday, in which he curiously references both Jay-Z and his own bar mitzvah.

It also leads to wondering about how such an allegedly open Hollywood secret remained just that, a secret, for so long, and why that silence has now been broken.

Across nearly three decades, the story stunningly reports, “after being confronted with allegations including sexual harassment and unwanted physical contact, Mr. Weinstein has reached at least eight settlements with women, according to two company officials speaking on the condition of anonymity.” And while “dozens of Mr. Weinstein’s former and current employees, from assistants to top executives, said they knew of inappropriate conduct while they worked for him,” it continues, “only a handful said they ever confronted him.”

And while some did report incidents — including, most notably, a former employee who wrote a detailed memo to Weinstein Company executives in 2015 — most told only fellow colleagues or friends.

“Some said they did not report the behavior because there were no witnesses and they feared retaliation by Mr. Weinstein. Others said they felt embarrassed. But most confided in co-workers,” the article noted, adding that speaking up “could have been costly,” as a job with him was “a privileged perch at the nexus of money, fame and art.”

According to Amy Blackstone, a sociology professor at the University of Maine who has expertise in workplace harassment, “This seems like the classic case where a man of great power is using that power to intimidate women.” Why such scenarios continue to play out is a difficult question to answer, she says, but an even harder question to answer is this: “How can we change it?”

The culture of harassment and silence

Deanna Foster, a Los Angeles–based forensic psychologist with an expertise in sexual harassment and hostile work environments, tells Yahoo Lifestyle that the type of behavior Weinstein is accused of “has less to do with lust or sexual desire than with power, control, and domination. It’s a means of devaluing a person in the workplace by calling attention to sexuality. It serves to keep a woman ‘in her place’ and to emphasize her role as subordinate.” And whether the harassment is “limited to vulgar comments or extends to quid pro quo [a you-give-me-what-I want, you-get-what-you-want manipulation],” she adds, “there is a running thread of intimidation, hierarchy, and assertion of control.”

And then there’s the added weight of these stories having come out of the great and powerful Hollywood. “Certain industries, in particular the entertainment industry, have an embedded and long-standing culture that tolerates sexual harassment,” Foster notes. “Organizational culture takes on a life and personality of its own. Culture starts with the top executives, and they are responsible for the tone that is set or tolerated throughout the organization.”

Being not only familiar with, but part of that culture, can lead the targets of harassment to respond with silence — as was the case with other recent allegations, including those regarding the conduct of both Roger Ailes and Bill Cosby. A 2016 study in Harvard Business Review, “Why We Fail to Report Sexual Harassment,” noted the findings of a 2015 survey — that 71 percent of women do not report sexual harassment — and found three main motivations for silence: fear of retaliation, the bystander effect (a phenomenon in which people in groups believe that someone else will do something), and masculine culture.

“What prevents women [or harassed men] from speaking up … is first and foremost fear that their job or work status or possibility of advancement will be at risk, or that they will be retaliated against in other ways for causing trouble,” Cheri Adrian, an L.A.-based forensic psychologist with expertise in sexual harassment, confirms for Yahoo Lifestyle.

But the list of other reasons for keeping quiet is a lengthy and complex one, she says, ticking off a slew: “Fear they won’t be believed, fear that they will be demeaned or humiliated, fear that they will be seen as oversensitive or weak, fear that they will be seen as having ‘asked for it,’ a lack of confidence that their own feelings and perceptions are trustworthy, cultural norms that permit sexual harassment or discourage confrontation of authority, workplace cultural norms that encourage or do not discourage sexual harassment, fear that they will be called upon to become involved in an uncomfortable public … investigation, a personal history of early relationships in which boundaries were not respected…, and a simple lack of knowledge about how to respond effectively.”

Foster adds another possible reason for silence: “Women may not be inclined to report sexual harassment simply because they view it as something they are expected to tolerate — whether it be at work or the grocery store.”

Why come forward years later, as is the case with the women who broke their silence in the New York Times this week? “People speak up later when they have less at risk, or when they have greater internal or external support,” Adrian explains, “or when they feel an obligation to prevent the harasser from continuing the behavior. Or when they see someone else come forward so that they feel greater support, or when there is a clear workplace policy against it and a safe way to report.”

Blaming the victim

Wondering what leads to such unbreakable silence in such a toxic culture of sexual harassment is natural, say experts. But calling it complicit, or believing it’s the root of the problem, is “absolutely unfair,” stresses Blackstone.

One such victim-blaming comment in the Times said, “This is where women must take some responsibility. Like it or not these men would not keep treating women this way if some women for whatever reason allowed themselves to be seduced. If it didn’t work some off the time they wouldn’t keep doing it. There was also a conspiracy of silence in all these cases. Victims either didn’t come forward or settled lawsuits with agreements that bought their silence. It is hard to feel sorry for women when they don’t fight back because of embarrassment or because they don’t want to hurt their careers.”

Instead of working to change the culture that allows men’s misbehavior, this approach simply points out that women haven’t fought back. That may not be the most helpful place to start. But useless or not, Foster notes that questioning the silence is human nature to some degree.

“Probably the biggest factor that promotes victim blaming is the perception that we all get what we deserve, and that if you do everything ‘right,’ bad things won’t happen to you,” she says. “It’s much easier to say, ‘She brought this on herself,’ or ‘That person must have done something to provoke such behavior,’ than to acknowledge that unfair and awful things might happen to you. Shifting focus away from the victimizer and onto the victim is a way of assuring ourselves of our own safety.”

At least one Times reader seems to have seen beyond that, commenting about Weinstein, “He’s a predator that got away with it for years because of the old boy’s network not just in Hollywood but in society in general. When will men teach boys that this despicable conduct is criminal in the eyes of the law and in the eyes of most girls and women even if not laws were on the books? When will men treat women with respect? I mean all men, because men who stay silent are also part of this pervasive problem.”

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Hugh Hefner lived a ‘glorified’ life of ‘pimping’ women, critics say

The American bias Hillary Clinton says is ‘darker’ than sexism: ‘It’s rage. Disgust. Hatred.’

Here’s how Cam Newton’s sexist comment sounded to women in sports

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.