Hemmerle celebrates 125 years with a collection inspired by its past as a medal-maker

TEFAF Maastricht opens its doors to the public this weekend, with art, antiques and design spanning over 7,000 years of history.

Hemmerle’s 125 years may pale in comparison, but it’s still a significant anniversary - all the more so when you consider that it has remained an independent jeweller, run by four generations of the same family, making pieces entirely by hand and selling them from a single boutique in Munich (along with a handful of art fairs around the world) for all that time.

The art link is important. Hemmerle’s jewels are unlike anything you’ll see on Bond Street or Place Vendome. They are, for want of a better phrase, an acquired taste - one which erudite collectors of art and design are drawn to.

To say it uses non-traditional materials is an understatement: non-precious iron, bronze, copper and aluminium are sometimes combined with rare gemstones of immense value, and other times with found objects including wood, pebbles, snail shells and, in one memorable brooch, Mikado pick-up sticks.

Each piece is a one-off, never to be repeated, although there are aesthetic constants which mean an educated eye can spot a Hemmerle design a mile off. Large, flat stones suspended from balls of spiky, inverted gems; mismatching earrings with ever so subtle variations of hue; old-cut diamonds and blackened metal; open bangles in smooth wood - all have become signatures of the house since the mid-1990s.

It hasn’t always been thus. Hemmerle was founded in 1893 when brothers Joseph and Anton took over a Munich goldsmith that specialised in creating medals and insignia. Two years later, the house was appointed supplier to the Bavarian royal court.

It later produced medals for the Vatican and, from 1905, was responsible for creating the Bavarian Maximilian Order (‘Maximiliansorden’) - an award for exceptional achievement in science and arts that it still creates today.

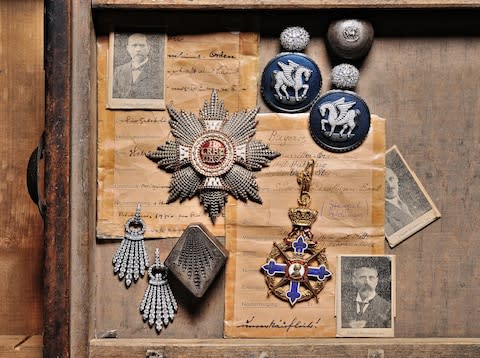

This heritage forms the basis of Hidden Treasures, the 11-strong anniversary collection unveiled at TEFAF. The name comes from a box of ancient embossing stamps that was stowed away in the cellars of the atelier on Maximilianstrasse, Hemmerle HQ since 1904.

The long-forgotten ceremonial insignias, engraved in negative on iron stamps, immediately sparked the imagination of Christian Hemmerle (great-grandson of Anton) and his wife Yasmin, and - with a little help from a historian - they also uncovered the matching ledger which revealed which stamp corresponded to which order. Then they set to work.

“It was like Christmas when we discovered that box,” says Yasmin, handling a pair of beautifully articulated blackened silver and diamond earrings, whose fan-like silhouette comes from a segment of the 19th-century Order of St Gregory.

Similar diamond fronds splay from a pair of antique cameos that happened to fit exactly the space in another stamp. “We treasure hunt - whatever we find we collect, then we wait for the perfect moment to use them,” she continues.

Elsewhere, the crown that tops the Maximiliansorden is depicted in matte black iron in another pair of earrings, encasing a glorious tassel of electric-blue sapphires, while a pair of prancing diamond Pegasus horses - the symbol for the arts which has long since been removed from the medal itself - appear on discs of midnight-blue anodised aluminium.

Turn these earrings over, and the reverse reveals the astronomical sign of Pegasus, with stars picked out in diamonds. This detail was added while the earrings were being made, a not-uncommon occurrence in the Hemmerle workshop, where designs often appear as little more than back-of-a-fag-packet pencil sketches - “our kind of hieroglyphics,” jokes Egyptian-born Yasmin.

The creation of each jewel is very much a collaborative effort between the Hemmerles and the individual craftsperson who makes each one. That’s part of what accounts for the longevity of Hemmerle’s 22-strong workforce of goldsmiths and gemsetters. Most have been there for a lifetime already and will retire with the company.

The 76-year-old workshop master still comes in twice a week, and one craftsman who joined 18 years ago is jokingly referred to as a “youngster”. There are real youngsters too, three apprentices who practice the ‘Hemmerle style’ for two years before they are allowed to touch a piece that will be sold.

The workshop itself is also a draw: a light-filled renovated townhouse ten minutes’ walk from the Hemmerle boutique, within which the workshop was located until 1999.

“We wanted it to be an inspiring environment. It has a good soul,” says Christian. Here goldsmiths use tools that date from his grandfather’s era, and work is distributed according to each person’s skills.

“Creations come to life depending heavily on talent,” he says, explaining that each piece is the work of a single goldsmith and gemsetter, and if it comes back in for repair it goes back to the same hands. “It means everyone takes pride in their work. Thanks to their input the final outcome will be even better than the original design.”

There’s no adherence to market demand or timescales. “It takes the time it takes. It’s not the most efficient process but it is the most artistic.” Design usually begins with the gemstone, which might be complemented by a pavé of meticulously colour-matched smaller stones.

Divided into dozens of boxes, these miniscule coloured gemstones are labelled according to Hemmerle’s precise categorisation: Grey (I, I, II), hot pink, petrol, lemon (I, II), dark golden, and, my favourite, ‘Schlamm’, meaning ‘muddy’. It might take two or three years to find the right combination of stones, and another few months to create a jewel.

Seeing the amount of work that goes into each piece, the price tags start to make sense. Hemmerle doesn’t communicate its prices, but rest assured that despite the resolutely un-blingy aesthetic, its jewellery is phenomenally expensive. And that’s part of the appeal.

While everyone has some idea of what that D-Flawless diamond on your finger might have cost, it takes an exceptionally educated eye - or a fellow Hemmerle connoisseur - to know the value of the 61-carat spessartite garnet hanging on a chunky iron chain around your neck.

“Our vision is to make one-of-a-kind jewellery that hopefully one day will be displayed in museums,” says Christian. These Hidden Treasures will be snapped up by Hemmerle collectors almost immediately, but if TEFAF is still running in another 125 years, don’t be surprised if they resurface.

TEFAF Mastricht, March 10 - 18, tefaf.com; hemmerle.com