Henderson history: Creation of family court judge job tied to new judicial center

The Henderson County Judicial Center and the county’s family court judgeship are practically twins but they were a long time in the womb.

The first glimmering of a judicial center came in The Gleaner of July 13, 1995, after a group of local and state officials met to begin sketching the financial foundations of the building.

“It’s not going to happen overnight,” said state Rep. Gross Lindsay. “But the way the state (government) works, you’ve got to get involved in the planning stage. That takes time.”

Based on that meeting, Judge-executive Sandy Watkins made a formal request to the state Administrative Office of the Courts to begin the planning process.

An article in The Gleaner of Nov. 15, 1998, first raised the idea of a family court judge, by which time the state AOC had signed off on the idea of a local judicial center. Kentucky’s first family court was created in Jefferson County in 1991 as a pilot program; by 1998 there were six of them and by 2002 there were 26.

“It’s a new breed of cat,” said Lindsay. “It doesn’t make sense to talk about getting any more judges until you’ve got a place to put them.” He favored a family judge because that would take caseload pressure off both circuit and district courts.

For example, family court handled divorces, child support, and adoptions – formerly in circuit court – while district court handled paternity cases, juvenile matters, and emergency protective orders. A family judge would preside over all those cases and more.

A study the county had commissioned from the Denver-based National Center for State Courts estimated a local family court would have an annual caseload of 1,720 cases, according to The Gleaner of Jan. 31, 1999. Land on Main Street had already been cleared for a judicial center by that point.

Lindsay tried to get a new judge position for Henderson County through the 2000 General Assembly but was unsuccessful because the money wasn’t in the judicial budget. He succeeded in the 2001 General Assembly, however, and The Gleaner of March 22 reported a bill creating the judgeship had been signed by the governor.

Lindsay cautioned, however, that the legislation wasn’t effective until April 1, and that he expected it would be mid-2002 before a family judge was appointed by the governor.

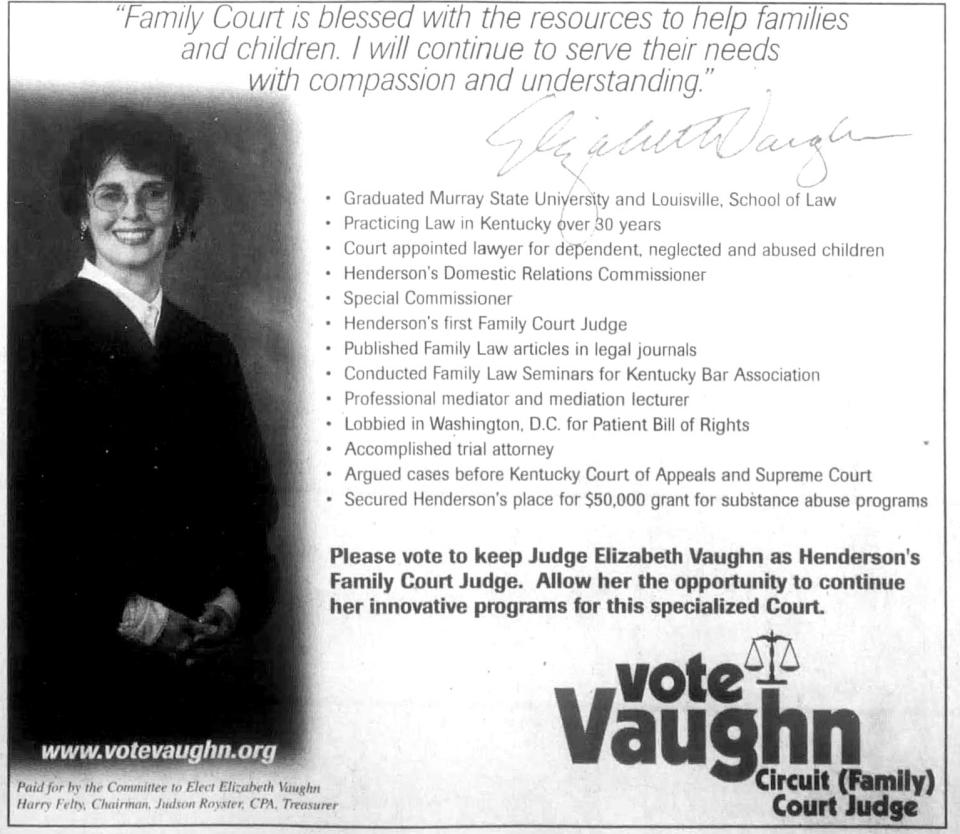

The Henderson County Judicial Center opened for business Jan. 28, 2002, and Elizabeth “Beth” Vaughn was appointed to the family court judgeship a little more than three months later. “It’s a new innovative position, and I’m looking forward to jumping in,” Vaughn said in the May 7 Gleaner.

She began her new duties June 3, despite having no staff, supplies nor equipment. “We may not be as efficient as people with telephones, but we’ll manage,” she said. “I’ve worked with a pencil and piece of paper for years so I can continue to do that until the computers and other things get here.”

The Gleaner ran a series of articles the first week of June 2002 looking at various aspects of family court, which was still a pilot program. An amendment to the state constitution was on the 2002 ballot; family courts would shut their doors if it were not approved, according to the state’s chief justice.

That series, which Judy Jenkins and I authored, was aimed at answering questions about family court. My part involved identifying a year’s worth of divorce cases involving minor children, pulling the case files, and entering pertinent information into a database program.

Related court files, such as criminal cases and domestic violence petitions, were also added to the database. About 300 court files were used in total.

The result was a list of 157 divorce cases involving 258 minor children. The analysis showed that divorces involving children were about twice as likely to be acrimonious than amiable, and that fully a third of the couples had engaged in premarital sex resulting in pregnancy.

The support staff for a family judge could ease the division for many couples, Vaughn said, because couples “get into a courtroom and find out that part of this is just an accounting problem, and no one’s taking into consideration the fact that my heart is broken, or I’ve worked really hard, or that someone was mean to me, or that I really don’t want to be separated from my child.”

Part of that, she said, was the adoption of no-fault divorce three decades earlier. “People are frustrated if they can’t tell their story – they just are. People want to bring these things to the court’s attention … and then they get into court, and somebody says it doesn’t make any difference.”

One part of the series surprised even the professionals involved – domestic violence was a factor in roughly half of the divorces involving minor children. Domestic violence was alleged in 77 of 157 cases and was documented in 65 of them. Of the 65 documented cases, 77 underage children were in the households.

Assistant County Attorney Sheila Nunley Farris was one of two competitors Vaughn faced during the appointment process, and she filed to run against her in the 2002 general election.

“My primary concern is children,” Farris said in The Gleaner of Oct. 27. “I feel that it’s a wonderful opportunity for me to have an impact on the lives of children and families. It won’t matter 100 years from now what kind of car you drive, what kind of house you live in, what kind of clothes you wear. But if you can impact the life of a child ….”

Gleaner Editor Ron Jenkins had predicted early on it was going to be a close race – and it certainly was. The election night tally showed that out of more than 12,000 votes cast only 47 separated them: 6,077 for Farris and 6,030 for Vaughn. The family judge constitutional amendment, on the other hand, was approved overwhelmingly, both locally and statewide.

The Gleaner of Nov. 7 reported Vaughn had asked for a recanvass. “I don’t expect a change in it,” she said. “I just owe it to my friends and supporters.”

Farris understood and said she would have done the same if their positions were reversed.

The Gleaner of Nov. 15 reported the results, which showed Vaughn picking up one more vote from the paper absentee ballots, which demonstrated Farris beat Vaughn by 46 votes. The final tally was 6,076 for Farris and 6,030 for Vaughn.

Farris served two decades as family court judge before stepping down; David Curlin was elected to the position in 2022. He took office at the beginning of 2023 but on Sept. 29 his license to practice law was indefinitely suspended by the Kentucky Supreme Court because he had failed to respond to two complaints (by former clients) filed against him with the Kentucky Bar Association and the supreme court.

Curlin is attempting to get the court to lift the suspension, maintaining an inability to obtain ADHD medication was the cause of his not responding to the complaints.

Farris is filling in as family court judge in the meantime.

100 YEARS AGO

The new Cairo high school had been accepted and contractor V.V. King was released from his bond, according to The Gleaner of Nov. 16, 1923.

“This school now has 150 pupils enrolled and is teaching 10 grades of work, and in three years will be an accredited high school.”

75 YEARS AGO

The Gleaner of Nov. 18, 1948, reported that a 17-year-old student armed with a battered .22 rifle had been arrested in front of Douglass High School, waiting for Principal H.B. Kirkwood.

On questioning, the boy admitted his plan to “knock the principal off.”

The boy was jailed and on appearing in front of County Judge Fred Vogel was sentenced to 10 days in jail. Kirkwood asked Vogel “to be as lenient as possible with the youth.”

50 YEARS AGO

The Henderson City School Board “let its hair down … and voted unanimously to delete the portions of the high school dress code that dealt with boys’ hair,” according to The Gleaner of Nov. 13, 1973.

It merely advised students to “avoid extremes.”

Henderson County High School, meanwhile, had held the line on hair length and as merger of the two school systems became an established fact in 1976 the merged board took a somewhat more lenient stance before school opened.

The Gleaner of July 21, 1976, reported the changes, which were midway between the policies of the two schools. “Students should always dress appropriately for the occasion and avoid extremes in dress, cosmetics and hair styles.”

Current rules at the high school contain the same admonition against extremes, but the code is more stringent – and much more detailed – than it was in the 1970s. For example, skirts and shorts must be knee-length, and tops that expose the midriff or cleavage are prohibited.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: Henderson history: Family court judge's creation tied to judicial center