Here's What Happened After My Brother Died, and We Decided to Donate His Organs

As soon as I read the Facebook message from my sister-in-law Dixie, I had a bad feeling.

My younger brother Michael, who’d just celebrated his 40th birthday, had been admitted to a Dallas hospital’s ICU after throwing up from a vicious headache that had started the night before. He’d fallen into a coma.

Hours later, Dixie called me, sobbing. The doctors had told her we should say goodbye—whatever was wrong wasn’t ever going to be right. As she held the phone to his ear, I said I loved him and asked if he could please hold on until I arrived and if he remembered the crickets we used to catch as kids—and then I faced my phone toward the chirping outside in the hot August night air. There was no reply, only the sound of Dixie’s heart breaking. I hung up, wiped away tears with the back of my hand, and booked the next flight to Dallas.

What I didn’t yet know was that my brother would soon become one of the 10,286 deceased individuals who gave the gift of life to others in 2017. Only three in 1,000 people die in a way that allows for organ donation—in the hospital from brain and circulatory death. Yet every 10 minutes another person is added to an organ waiting list of more than 113,000 individuals, including almost 2,000 children. Twenty people die daily while waiting to receive a functioning heart, kidney, or other organ.

The Choice to Donate Organs

Though blood had flooded Michael’s brain, he simply appeared fast asleep when I saw him the next day. After I arrived, Dixie finally slept. Around midnight, his heart rate and temperature spiked. A worried-looking nurse came to perform a few tests. She whispered that his reflexes no longer operated as they would if his brain were functioning normally.

The next morning, the doctors determined that he was brain-dead, a result of a stroke due to untreated high blood pressure. Dixie and Michael had struggled financially at times, and he hadn’t had health insurance or checkups for a while.

Dixie then had to make a wrenching decision—whether to donate Michael’s organs. My brother had never indicated whether he wanted to be a donor, which isn’t uncommon. Up to 95% of U.S.adults support organ donation in theory, but only 58% are registered donors.

Dixie thought about it for a few hours.“It seems like something he would want,” she decided aloud, lying next to him on the hospital bed, her hand on his chest where his heart still beat. His death meant someone else could live.

After the hospital had exhausted all options for treatment, the Organ Procurement Organization (OPO) Southwest Transplant Alliance stepped in. The family care coordinator tried to explain what would come next, but nothing could have prepared us for the waiting and uncertainty that followed.

Dixie was asked about Michael’s overall health and any complicating factors that might make organ matching more difficult, such as whether he had smoked (yes, in high school) or had heart problems (no). However, very few medical conditions or diseases preclude donation of any organs.

Simultaneously, the OPO staff began the organ-allocation process, using the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) database. OPTN matched Michael’s organs to potential recipients, incorporating factors such as blood type, height, weight, and even organ size along with the potential recipient’s urgency of need.

We were about to become part of a new clan of sorts: surviving family members of organ donors. “This is the crappiest club filled with the most amazing humans who have lost loved ones too soon,” said Deanna Santana, whose 17-year-old son, Scott, hit his head against a seat in an accident at a relatively slow 30 mph. Scott was wearing a seat belt, but his brain injury was fatal. In the hospital, he “looked perfect, but he was so badly injured he couldn’t recover,” Deanna told me softly.

Finding the Right Recipients

As we would discover, there’s usually a day or three between declaration of brain death and the organ-recovery surgery as procedures and processes match donors with recipients. There’s a perception that the donation and transplant process takes place with intense speed, but that isn’t the case at the start.

“It’s a blessing to spend more time with a loved one,” Deanna recently said on the phone regarding the process. Her son and daughter had long rolled their eyes at her frequent advice to look for a silver lining no matter how bad the situation. But on the day Scott’s five organs were recovered, her 20-year-old daughter, Marissa, offered wise words. She turned to her parents and said, “On the worst day of our lives, five people are having the best day of their lives.”

Each donor can potentially save up to eight lives through organ donation and enhance another 75 with tissue donation. New advances have led to innovations such as hand and face transplants.

OPO staff evaluated Michael’s organs in person. To determine suitability, they communicated remotely with transplant surgeons whose patients were matches. During these assessments, we left the room and sat in the hallway. After surveying Michael’s heart, a woman on the ultrasound team approached us. “He has one of the most perfect hearts we’ve ever seen,” she said.

We had more time to wait as surgeons accepted organs, an operating room was scheduled, and surgeons coordinated flights for organ recovery. This part of the process does rely on fast turnaround times. Kidneys can stay outside the body for up to 48 hours and can be shipped (on ice) across the country, while other organs such as hearts and lungs might last for only four hours.

“One of the most profound things Scott taught me is that there’s a whole community of people who are sick and in immediate need,” Deanna said. “We said yes to donation so another family wouldn’t have to say goodbye sooner than they should.”

Finding Living Donors

Kidneys are most urgently needed, followed by livers, hearts, and lungs. Matching tissue type prevents the recipient’s body from activating an immune response that would lead it to reject the kidney as if it were a foreign object.

In Montgomery, AL, Verna Johnson, 50, had waited for a kidney for over a year. She was facing advanced renal disease, which had claimed her sister’s life after 11 years on a transplant list. Verna had needed to stop working as a mental health counselor. Waiting was agonizing.

Desperate, she decided to take action and “wake them up, shake them up,” she said, referring to those who didn’t know about donation or misunderstood the safety of the living kidney donation procedure. Typically, healthy donors require only a two-day hospital stay after a low-risk surgery that costs the donor nothing. Humans don’t need both kidneys to live a good life, Verna notes: “You can live with just one, and share your spare.”

For months, Verna’s photo appeared on billboards in the Montgomery area that said, “Verna needs a kidney. Could you be her miracle?” and offered the phone number of the University of Alabama location where she was being treated. The billboards worked, she said. Those who called were screened to see if they were matches for Verna, but those who weren’t a fit for her probably were for someone else. “If they matched with another person, that paid it forward for me” in a domino effect, she says. Finally, last October, a stranger matched with Verna: “God chose her for me,” she says. They are sisters now, she says, forever connected.

Living With a Donated Organ

Terry Box works with liver transplant patients at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Most liver recipients are older and might wait months to years for a transplant. However, a living donor can donate part of a liver and the parts will regrow to full size in the donor and the recipient.

“Organ transplantation is as close to a miracle as we have in medicine,” Terry says. “Some of us have a critical organ replaced and our health restored, to return to life and work and get back to some normalcy.” His voice cracks and halts a bit: It turns out he’s an organ recipient too. “From a community perspective, putting a value on that is impossible. It’s a boon to us all, a great benefit to the recipient and to the community that supports that recipient,” he says.

At 4:30 p.m. one day, after three nerve-racking months on the liver-recipient waiting list, Terry received the call. His physician was en route to a prospective donor in California. Terry went to the hospital’s intensive care unit to prepare in case it was a go. At 1:30 a.m., the hospital received word that Terry’s doctor was bringing back the liver.

A 13-hour transplant procedure ended successfully. Terry was lucky, he knows, as some patients experience several dry runs before a successful transplant.

Survivor’s guilt can weigh heavily on recipients of successful transplants, who are aware that “some family in their hour of grief was courageous enough to make that decision,” Terry says. One way to pay them back? For the recipient to live life in honor of that borrowed organ, he says.

Grieving family members aren’t obligated to meet the recipients of their loved ones’ organs, and recipients are sometimes hesitant to reach out. As with adoption, both sides must be receptive. For the first few years after Scott died, Deanna’s daughter, Marissa, wasn’t ready. Then the Santanas met three of the five recipients of his organs. Among them was a 74-year-old man who provided a recording of his heartbeat—her son’s heartbeat—which Deanna placed in one of Scott’s stuffed animals from childhood so she could hold it when she missed her son. A16-year-old girl received Scott’s corneas and went from fearfully clutching her father’s arm everywhere she went to taking solo bus trips and fully participating in life.

Saying Goodbye

Some families worry that organ donation will lead to bodily disfigurement, but that’s another myth—an open-casket funeral would still have been possible for my brother. For us it was a moot point, as Dixie planned to spread his ashes in the Columbia River Gorge area, where we grew up.

Machines kept Michael’s body alive in the interim. Our younger brother, Andrew, flew in from California; he collapsed, crying, upon seeing Michael hooked up to a ventilator. But we found ways to laugh and reminisce about Michael’s sense of humor, and we teased him about having convinced us—spread so far around the country—to hang out with him.

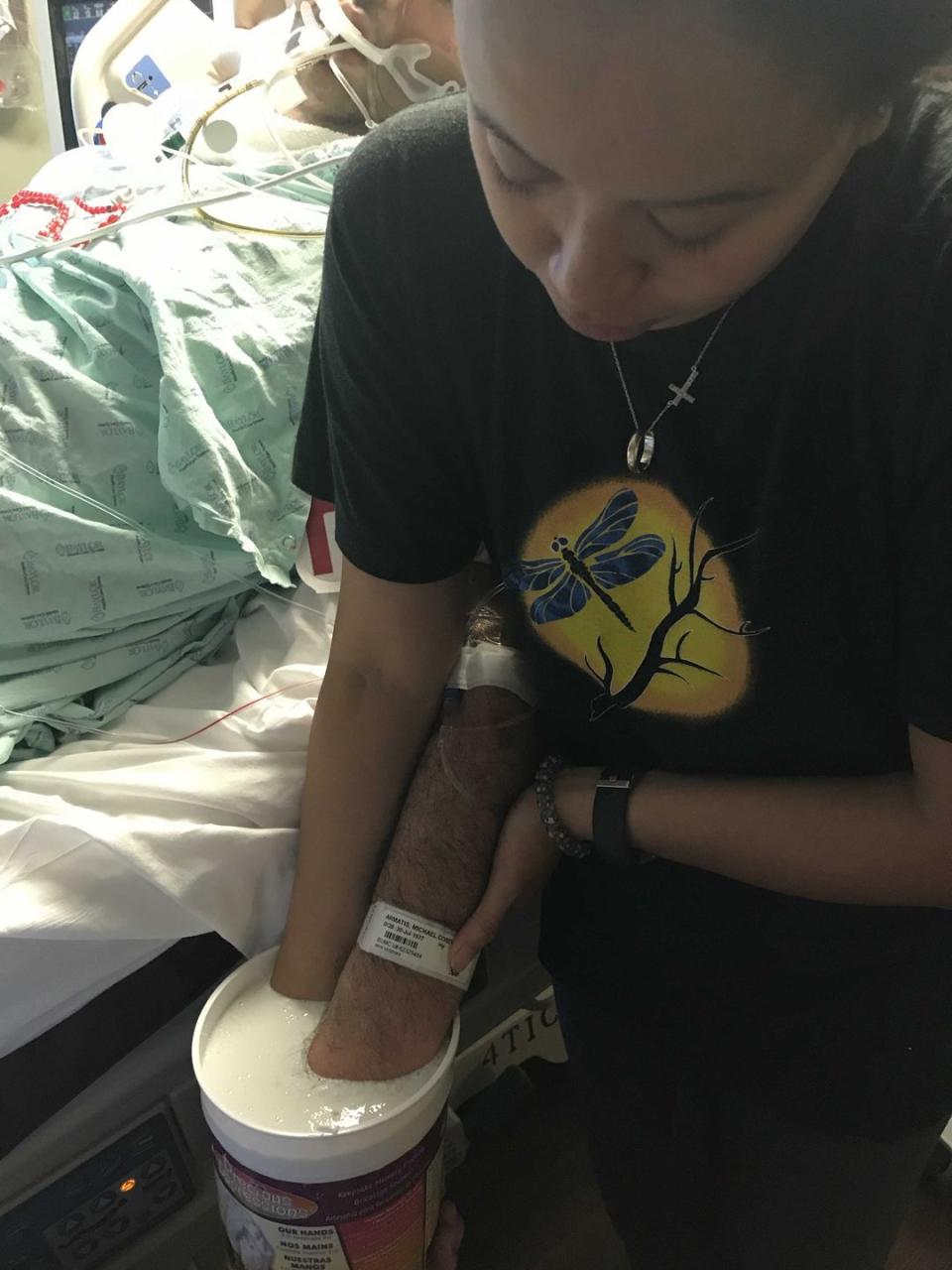

An artist came through and placed Michael’s and Dixie’s hands, intertwined, in a bucket of plaster. The cast would be a keepsake Dixie could hold on to even after death had parted them.

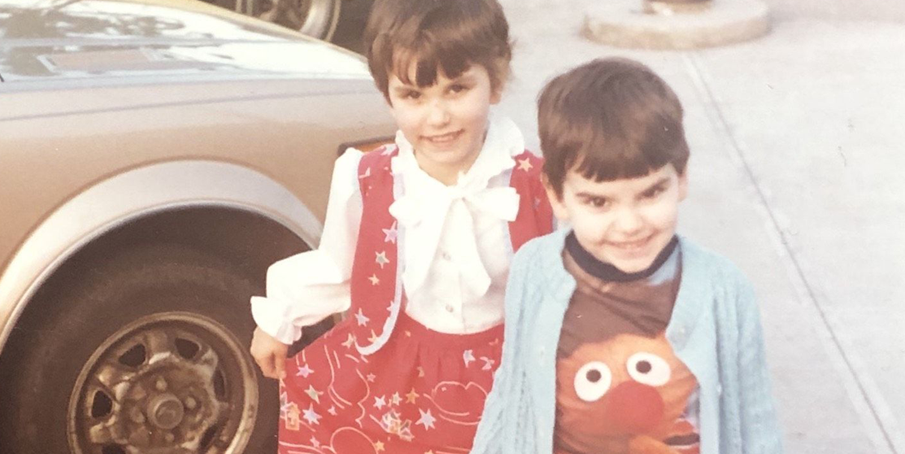

The hospital encouraged Dixie to snip bits of Michael’s dark brown hair (what he had left, we joked—he’d been balding for a while). I inhaled the scent of the skin near his temple, where his pulse still throbbed. He smelled the same as when we were little, when we played superheroes, tying towels around our necks, arms pointed forward as if flying.

Early in the morning three days after he was admitted, staff prepared Michael for the operating room. We wouldn’t be with him when they took him off the ventilator—he’d remain on it during surgery. As they wheeled him out, we cued up an Everclear grunge hit he’d often played for Dixie, and we said goodbye.

I will buy you that big house

Way up in the west hills

I will buy you a new life

I will buy you a new life

Michael’s photograph was added to the hospital’s “wall of heroes.” Finally he would be a real superhero.

This article originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of Prevention.

Support from readers like you helps us do our best work. Go here to subscribe to Prevention and get 12 FREE gifts. And sign up for our FREE newsletter here for daily health, nutrition, and fitness advice.

You Might Also Like