Irvine Welsh interview: ‘We’re having a nationwide nervous breakdown’

Irvine Welsh is describing the streets of Camden, in London, where he now lives. “It used to be that you had the street people, who were alkies or junkies, and everyone else,” he says. “But you walk around Camden today and everyone seems to be having this crazy crisis. Everyone is on prescription drugs. There’s this mad edge in the air. It’s great fuel for a novelist.”

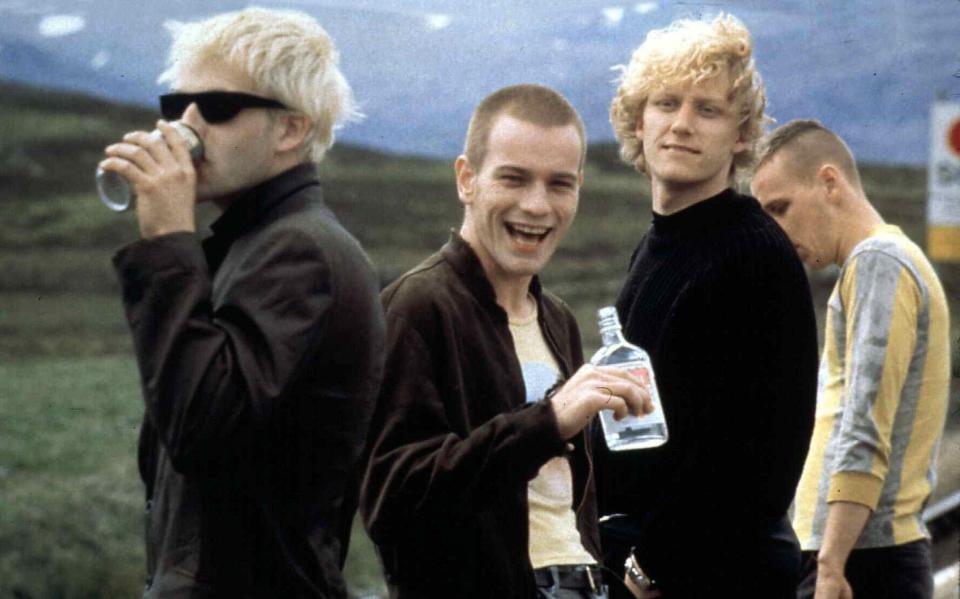

Particularly if you are Irvine Welsh. The Trainspotting author has spent a career chronicling the lives of the psychotic, the dysfunctional and the insanely violent ever since his 1993 debut caught the despairing housing-scheme hedonism of Scotland’s Class A generation like lightning in a bottle.

His novels, some of which followed Trainspotting characters into adulthood, are a Grand Guignol of excess and depravity, teeming with outsized misfits and maniacs. Yet where Trainspotting, his most brutally social-realist book, depicted the hard-core desperation of a 1980s recession-blasted underclass, he reckons today’s opioid crisis has turned drug addiction mainstream.

“You see mums pushing prams who are out of it, you see hipster jakies [homeless alcoholics] begging for help. Everything is medicalised. My mum died in the summer and when I was clearing out her cabinet, I realised she had a pill for practically everything.” Hang on, I say, you’ve taken a pill or two in your time. “Yes, but I only did it to have a good time!”

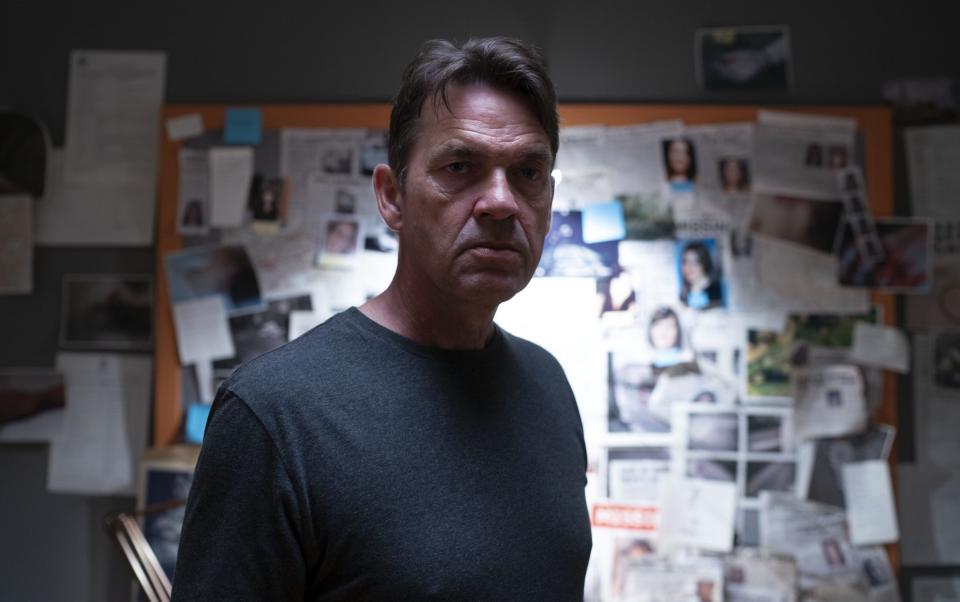

This Thursday, Welsh’s 2022 novel The Long Knives, his most recent, arrives on TV screens. The book is a sequel to 2008’s Crime, also adapted for television (The Long Knives is billed as Crime series two), and sees Welsh’s tormented DI Ray Lennox attempting once again to exorcise his personal demons by unravelling the filthy web of Establishment corruption behind the hushed-up murder and castration of a Conservative MP in a hotel room.

Scenes of epic gore are interspersed with moody shots of Lennox in the rain, although the pace is more controlled than the novel, whose pages open with a gut-churning spectacle that’s extreme even by Welsh’s operatic standards.

“When I write a novel, it’s complete self-indulgence,” he admits. “You have to be more aware of your audience when you write for TV. British TV crime tends to be very traditional, very procedural. Yet I was in the States when all the psychological crime stuff was kicking off [he lived in Miami for 10 years before returning to Britain during the pandemic]. I was raised on HBO. So we’ve tried to make this a more character-driven existential thriller. I see Lennox as more a vigilante than a cop. He’s trying to rid the world of all the abuses he couldn’t protect himself from as a kid.”

In person, Welsh is nothing like the garrulous, chaotic, stream-of-consciousness narrator that invariably powers his books. He’s genial, generous and an acute social commentator, sometimes lapsing into the sort of Marxist theorising beloved of earnest sociology students. But his assessments rarely feel wrong. He believes Lennox, for instance, for all his psychological specificity, exemplifies, in his restless lonely unhappiness, a nationwide nervous breakdown.

“Everyone today is in a crisis brought on by technology,” says Welsh. “Everyone is in this very weird place where all the things that held us together under capitalism and the division of labour are breaking down. We’ve created this artificial zoo, and it’s destroying us. We’re all searching for something to give our lives meaning, be it pills, an operation, a new identity. We’ve forgotten that feeling pain and discomfort is part of being human, so we try and edit it out of our lives. And, yes, the white heterosexual middle-aged man is in the same boat as the trans-curious teen.”

Ah, yes, the trans-curious teen. There are two trans characters in The Long Knives, including Fraser, the child of Lennox’s sister, and played by star Dougray Scott’s own son Gabriel. Welsh consulted sensitivity readers when he wrote the book and is deeply sympathetic to the trans cause, even if he despairs over the ugly oppositional language that discussions on the subject often provoke. “You can’t redesign the world in a democratic way,” he argues. “You can’t say to people ‘This is how we have to be from now on’. You have to win people over. But instead we create these antagonistic functions in which people abuse each other on social media. I think trans people should be supported and that women should have spaces in which they feel comfortable, but we need to find a new way of talking about it.”

Does he believe the pickle the SNP found themselves in over trans rights and women’s prisons under Nicola Sturgeon has badly damaged the public perception of the SNP and their cause? He is, after all, a vocal believer in Scottish independence. He dodges the question, saying only that he is not party political. “I think the era of the super state is over. We need small communities who take control of themselves. I’d like to see all these communities, be it in Scotland or in Spain, standing up for each other.” This sounds odd, coming from someone who was very opposed to Brexit. His main beef, though, is with politicians who, he says, often adopt positions on policies with which they don’t agree. How does he rate Labour’s chances in Scotland now? “It’s tricky, even if they do do well, because that schism between unionism and independence isn’t going away. The problem is that people are no longer party political in the way they used to be. They lend parties their voices, but they don’t lend them their hearts.”

Welsh is 64. He’s a rare example of a novelist who having written a zeitgeist-defining novel, never produced another book to match it, yet who has remained culturally relevant and impossible to ignore. He recently married, for the third time (he has no children), and currently splits his time between London and Edinburgh, where he spent his childhood in Muirhouse, to the north of the city. In many respects, Trainspotting was a tribute to the people he grew up with who were left behind by Thatcherism – the first generation of working-class people to find themselves facing a world without paid work. “Everyone is now facing a future without paid work,” he says. All the same, he mourns the wit, the buzz, the exhilarating Choose Life bravado that defined Renton and Sick Boy et al, whatever the chaos of their lives.

“There’s no street culture anymore,” he says. “I’ve got a new nov-ella coming out, called Real Life, about kids today in a housing scheme, and just like with the Train-spotting kids, for them the real world outside is a threatening place. But the difference is that today’s kids are constantly online, racking up huge gaming scores, watching hard-core pornography, ordering all their food online. Every-thing is geared to an addiction in a different form.” He thinks the cultural consequences of a life lived online are catastrophic. “We’re in danger of moving into a post-art society. We don’t need to worry about the robots or AI, but our own numbing of our ambition and passion for art. I run a record label and there are people creating dance music who’ve never set foot inside a club. This is what we are losing.”

Which novelists are capturing this new digital apocalypse? “I don’t think it’s possible to write that sort of novel, a novel like Trainspotting, any more. We live in a media-saturated culture where everything is an algorithm or a pastiche of what went before. I do sometimes catch myself and think I sound like some old bastard down the pub. But, -honestly,” he says with a wry chuckle, “it’s a terrible time to be alive.”

Crime series 2 is on ITVX from Thursday