Is it OK to ask me, 'What are you?'

Sounds like an odd question, doesn’t it? What’s even stranger, for me, is that it’s the No. 1 question I am asked most often. And more interesting than the question itself was the strategy I developed for fielding it. Upon self-reflection, I felt it was time for a change, but I realized I would need everyone’s help.

I noticed that when most people ask me this question, because, let’s face it, nine times out of 10 it’s a white person who asks me, I will always answer in a particular order. I say, “My father is German-Ecuadorian, and my mother is from Honduras.” If anyone other than a white person asks, I simply say I’m Latina — I was born here (in the U.S.), but my ethnic background is Latin American.

The foundation for my coping strategy was laid even before my birth in my parents, particularly in my father, who carries the German bloodlines and was told this made him “special” — simply for being less brown. In fact, he is quite fair and takes after his father, Hans Hoppe, the most out of his siblings. In addition to key physical attributes, he inherited a German last name, which allowed him to assimilate relatively easily in the U.S., at least in the beginning.

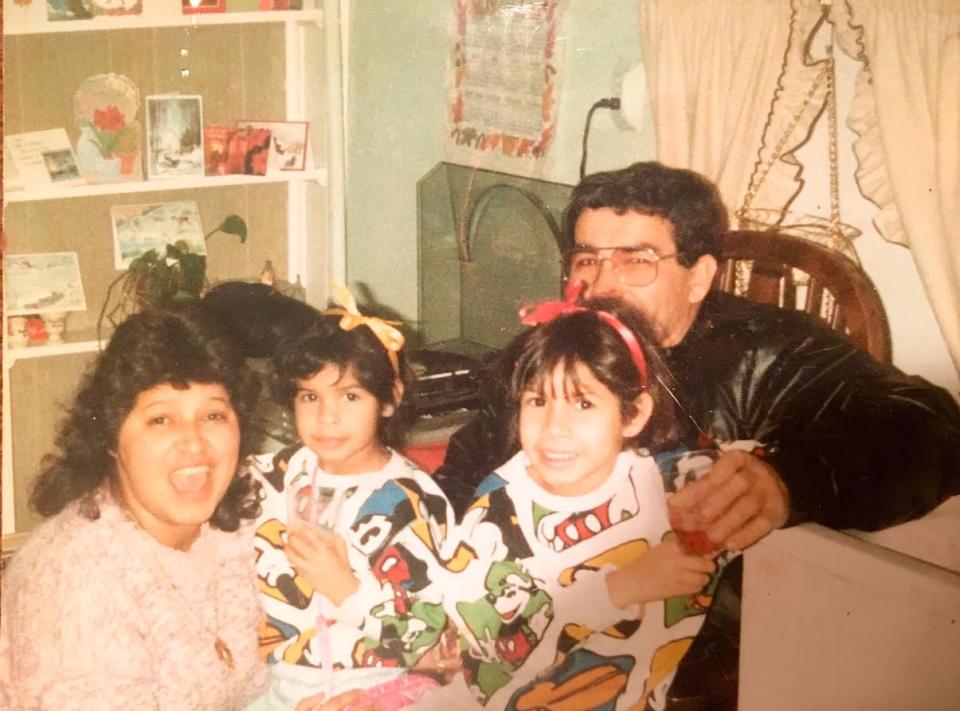

My mother, on the other hand, had the opposite experience. Her “look” would be considered more ethnically identifiable and her skin tone significantly darker than my father. She is a unique and beautiful woman. But she was not taught to embrace or celebrate who she is. She was taught to defend it — even from her own family. Once as a child, she and her cousins were all given dolls for Christmas. All the girls received white dolls with blond hair, save my mother who was given a black doll with black hair. Guess Mattel hadn’t come up with the Latinx version yet. Neither one of these dolls reflected any of the girls accurately, and neither doll was better or worse — the damage was in the messaging. My mother was consistently told she was different and it was because of her skin tone, which was not her family’s preference. Her life experiences validated these ignorant ideas, and, naturally, she grew to be quite defensive.

Later in life, my mother had three daughters. I happen to be the daughter who most inherited her unique features. Two in particular: skin tone and hair texture. My nickname to this day is “Negrita,” which is a term of endearment technically translated to be “black girl” and the cultural interpretation is “cute little dark or black girl.” While my parents never mirrored the racism and ignorance of their upbringing — when my grandmother would tell me to stay out of the sun lest I get “darker” they would vehemently reject it — my mother’s sense of “other” was imbibed by me.

Simultaneously, the story of my German heritage from my father’s side was fed to us as the Holy Grail. It became a huge part of my identity because it was posed to us as being so special. Thus, when I struggled to fit in at my predominantly white school, my German-ness (i.e., “whiteness”) became a tool for navigating socially isolating situations.

In grammar school when we began studying colonization and researched the various Native American tribes, we learned about the Hopi tribe of northeastern Arizona. My last name, Hoppe, is German not American Indian as is very often the assumption. The class, including the teacher, felt they had cracked the code on my lineage and naturally assigned me this tribe for the class project. Everyone seemed disappointed that this was not only inaccurate but also quite ignorant. Without a thought, they drew a correlation from the sound of my name to the look of my face and skin tone. And, guess what, guys — it’s not that simple an equation. And while it’s not necessarily malicious either, the effects are profound because it creates a sense of “other” in the “subject.” In this case, the subject was me. And that sense will design a pattern of behavior to cope with the feeling of isolation, which creates a false self. Meaning: Because I never felt I could safely present my true self, I affected “qualities” that could be more easily identified with in order to be “accepted” in a predominantly white environment.

I compartmentalized my person as such: the things about me that I need to protect that make me “other” and the things about me that keep me “safe” and “part of.”

But the truth is the tiny bit of me that is German (1/8 to be exact) has nothing to do with who I am — none of the German customs nor the language were passed down. It was just a childhood story that was told to me with pride because it was culturally ingrained in us to believe that it made our bloodlines “better.” And I, in turn, used it to cope with my feelings of isolation and as a means of fitting in. And to be honest, it worked. The problem was it didn’t feel authentic. And as I came into adulthood, the persistent question started to make me angry. My responses became impatient, reactionary, or passive-aggressive, and that wasn’t the real me either. Of course, I don’t want to be insulted, but it’s not really about me. But when you ask me that question, you actually get further away from the truth, and I, in turn, begin to make assumptions about you.

I assume (from experience) that you are asking out of a curiosity, which is fair enough I guess, but also a need to understand what the heck you are looking at. The problem with this is that it creates separation between us. You’ve reminded me that you noticed we’re different, which is never a good feeling. And I, now cast as the mysterious mystery, must bridge the gap by neutralizing my “ethnic-ness” by demonstrating my “whiteness” (i.e., saying I’m of partial German decent first). I must then back that up with an aptitude for imitating my idea of how a white person behaves despite the fact that I’m brown.

Now, I’m a grown woman and I understand hearing this question can be quite triggering for me, especially in today’s heated political climate. So this is my opportunity to move the conversation forward by not taking it personally, and having the courage to be myself despite my fears. Likewise, it is important for you to acknowledge that the question you’re asking is not a simple one. In fact, it’s quite loaded and therefore ineffective. And when it’s posed, this is my thought process and instinctual reaction. And I know the root of it is fear — an idea that I’m “too much” or different — that I will not be accepted. What I realized is while I’m jumping through hoops trying to make you more comfortable, I’m just as scared. So maybe you don’t need to know “what” I am — you can just get to know “who” I am? I promise you, it will come up.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.