How Jen Sey Went From Elite Gymnast to CMO of Levi's

...and part-time film producer, with the recent debut of "Athlete A."

In our long-running series "How I'm Making It," we talk to people making a living in the fashion and beauty industries about how they broke in and found success.

When Jen Sey was growing up, she never envisioned a career in fashion or retail — mainly because she didn't have time. At age 10, she was already five years into a competitive gymnastics career, and made her first elite national team, which meant she would start training up to 50 hours a week.

"When I think about my childhood, I don't remember a lot else, other than training — the joys of it and the difficulties," she tells me over the phone from San Francisco.

Sey went on to win the U.S. National Gymnastics Championship title in 1986, despite suffering a devastating injury the year prior. When she ultimately decided to retire from gymnastics and go to college at Stanford, she says she was "broken, both physically and emotionally." She made a clean break from the sport — that is, until 2009, when she published "Chalked Up," her first book, which detailed the physical and emotional toll gymnastics took on her and exposed a dark side to the sport.

Despite backlash from the gymnastics community, Sey became an outspoken advocate for athletes, which led to her producing "Athlete A," a powerful new documentary on Netflix that details the biggest sexual abuse scandal in sports history, involving former USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar. (As inspiring as it is deeply upsetting, the film will change the way you look at elite gymnastics.)

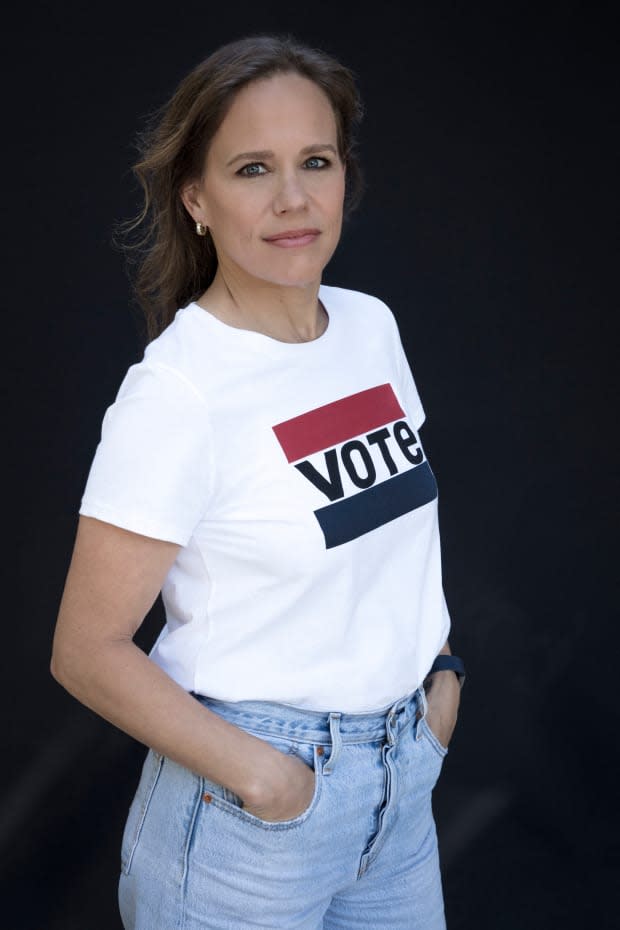

All the while, Sey has spent the last 20 years working her way up the corporate ladder at Levi's, where she's been chief marketing officer for the past seven. In addition to stewarding the iconic denim brand back to a place of relevance and authenticity, she has led communications around a number of social issues and charitable initiatives at the company — skills have really been put to the test as of late, with Levi's being quick to react to the Covid-19 crisis and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Related Articles

Levi's Commits $3 Million to Support Communities Impacted by Covid-19

Why Brands and Publications Are Using Social Media to Spotlight Artists and Performers Right Now

Levi's Coachella Activations Are Meant to Build on the Festival Presence the Brand Already Has

Sey took some time to chat with us about working through these critical cultural moments, building a career at Levi's while also pursuing personal projects and how speaking out about gymnastics helped her find her voice at work.

What was your process of transitioning from gymnastics to college and, ultimately, marketing?

I wanted to figure out who I was, because I had no idea who I was without the sport. That was a long process for me in my 20s. I really had creative aspirations, to be a writer and a filmmaker — which is ironic, because it ended up being true — but I also needed to make money.

[After college] I ended up taking a job at an advertising agency working on Levi's, and it was all [because I] knew someone who knew someone. I found it was a great mix of creative skills and cultural acuity, and then served deeply on the political skills as well. I liked that balance, so I continued. I also liked the camaraderie: Gymnastics is an individual sport, and I love being part of a team in the work environment. Honestly, despite my aspirations to write — and when I say "be a filmmaker," I wanted to be a screenwriter — I didn't want to be alone that much. I was afraid of that as the sole pursuit in my life.

I ended up staying at [advertising agency] FCB for about three years, and then I went on to work at Banana Republic for about three years. I found myself at Levi's in 1999.

I think, at first, I had a fraught relationship with it, because I was torn. I wanted to do something less commercial, wanted to pursue the more individualistic, creative things. What I found out is I could do both — I could exercise both parts of my brain and personality. I ended up writing a book in 2008 and found myself on the edge of 40 being a writer, which was exciting. I became an outspoken voice and whistleblower on abuse within the athletic community, and ended up writing more for the New York Times and some other outlets.

Before that, I had applied to film school, in 2003, and got into Columbia, but ended up not going because I was the breadwinner in my family and it was just impractical at that point. Because I investigated attending film school, I found out you just make two short films, so I was like, "Well, I'll just make two short films, I don't need to pay whatever, $60,000 a year to do it." So I was always dabbling creatively on the side.

How did you get involved in "Athlete A"?

I ended up getting to know a lot of the survivors in the Nassar case and meeting a lawyer, advising him on what this culture is like, so he understood it. As I got to know everyone and stood with them, I felt this could be a movie. I thought that more people are going to watch a film than read a book or a journalistic account, unfortunately. I thought it deserved that kind of widespread attention. So I just started talking to people and was quickly introduced to a woman who produces films in San Francisco. She tends to focus on films with female-centered subject matter. She was intrigued by my little pitch and she introduced me to the directors.

When you left gymnastics, did you see yourself still being involved all these years later?

I walked away with such a bad taste in my mouth. I was so physically broken. I had an eating disorder. I was, emotionally, a wreck. I was bitter. I hadn't reconciled my time in the sport, and I was angry with my parents and my coaches. I was not whole really, so I was aggressively against the sport. The irony was that writing a book was really meant, in my mind, to put it all to wraps, to help me understand my time in the sport. It helped me feel grateful but also make peace with the bad stuff and fully walk away from it. I'm so much more involved in the sport now at 51 than I was at 25 because I've become an athlete advocate and this outspoken voice. At this point, at my age, I'm really not afraid to say anything.

What do you hope people take away from 'Athlete A'?

It's the biggest abuse scandal in sports that I can think of. I still don't think people really know about it. I still don't know that parents speak enough about it when they send their kids off to play sports, which I think is a great activity, but they should be clear what the coach's philosophy is. I would like for [teens] to watch it and understand that their voice matters, that their experience matters and that they can and should speak up when something isn't right.

I feel like if I'd been prepared for that before something happened, abuse happened, I would have been confident enough to say or at least I would have felt I had the permission to say, "No, don't treat me that way." But obedience was beaten into us. So not only did I not feel comfortable saying that, I believe that the abuse heaped upon me was my own fault because I was too lazy or bad or whatever. I think we can prepare kids to not accept poor treatment — especially girls.

Of course, I hope that it keeps the pressure on USA Gymnastics, because they really haven't made the necessary changes, in my opinion and I think in the opinion of all the survivors. It's still not a child-first organization. It's still an organization that, I would argue, put winning and money and medals over children — and they are children, to be clear.

Going back to Levi's, how did you get started there and work your way up the ranks?

I started Levi's in June 1999. I was an Assistant Marketing Manager for a brand that no longer exists called L2. I must have just turned 30 and I was about to get married. I went out on maternity leave and that brand went away, so when I came back, I joined the Levi's brand and was the director of marketing for the U.S., before we were structured globally, for about four years. Since then, I've held a variety of jobs in and outside of marketing. I actually moved into strategy right after the U.S. director position.

I served as an advisor to the senior leadership. I did things like craft a strategic business plan, start a new opportunity and things I had no idea how to do — but I could Google, so I figured it out pretty quickly. I built my Excel and PowerPoint skills and honed my math skills as well. But it was really the best thing I could've ever done because I got a much more well-rounded view of the business, and I think that makes me a stronger marketer with a business-driving perspective and not just a brand-building perspective. I went from there to lead the Dockers marketing organization, and that was a global role.

From there, I went on to lead the e-commerce business unit and really was the first global leader in that business. I pitched the idea to the CEO that we needed a dedicated e-commerce business unit — here was the cost, here was the investment and here was the org. Then, I, of course, asked to be able to run it. I think he was pretty hesitant to let me do it because I really didn't have the experience. But I was pushy, I guess. I ran that business for just under three years, and then the CEO, Chip Bergh, asked me to step into the CMO role. I've been in that role for seven years.

In taking the CMO role, were there any specific goals that you had for the company? Were there things you wanted to change? What was your approach when you got started?

It's no secret that our brand and our business had been suffering. We'd been in pretty consistent decline for at least a decade and a half, since the late '90s. I knew the brand really well, so I could start quickly. I felt the most important things [were], one, to get back to the authentic heart and soul of what this brand is about.

I think there were times, when [the brand] was suffering, that we were so afraid of not being cool — because we were old and a heritage brand — that we inauthentically chased the edge of cool. And it didn't work. My mission was to get us back to that heart and soul of the brand, which is authentic and warm and inviting and inclusive.

Then, the second piece was really about a great integration partnership with product. I feel like I actually have that with Karen Hillman, who's the head of design. She started her role almost exactly the same time as I started as the CMO.

What she's been able to do with women specifically, in terms of bringing that same brand vision to life through product with a distinct aesthetic — incredibly relevant and stylish and at the same time very authentic — has been remarkable. I think that she and I just have this partnership, and we agree on what the core and the soul of the brand is. Then we each go off and do our part of it and come together at the right moments in time. I think if you deliver on a brand promise that the product fails to, then that's not going to work. The inverse is true as well.

Interesting, I don't know if people realize that, or if that's even normal for marketing and product to be that intertwined.

I think it's not [normal]. She and I have both experienced that in other roles, and we wanted that. We had a common vision. I think if we didn't have so much alignment in terms of what we believe the brand could be, it could have been more difficult and we would have been less successful. But in a lot of apparel companies, it's a bit of an older model, where merchants rule the organization... marketing is there to make the ad that they're told to make. I think that's a failing. Everyone needs to hold the brand dear and champion the brand. I just do that through communication, and she does that through product. But we both are the stewards for the brand.

I'd love to hear a bit about what this year's been like for you, from Covid-19 disrupting festival season and other events to the Black Lives Matter movement once again top of mind for many — all of which Levi's has been vocal about. When there's a global situation like this, what is your first step in addressing that as a brand?

Well, we're in a slightly different position than some brands because I do think we've always been very value-led. That's how we run our business. We haven't always communicated it. In fact, that's the new part for us, leading with that in our communication. We integrated factories in the South before the law required it. We offered same-sex partner benefits in 1992 and were the first Fortune 500 company to do so. I mean these examples, they go on and on. We just didn't talk about it because that felt unnecessary. You did the right thing, you didn't have to beat your chest about it. But now, we know the younger consumers — both Gen Z and millennials — want to know what you stand for. So the change for us in the last few years [has been] figuring out how to communicate our stance on issues without losing the authenticity and the humility that I think the brand possesses.

When Covid hit, it wasn't a matter of, "Are we going to be value led?" It was how. Very quickly, at least from me and my team, we felt it was not the time to aggressively market and sell people. People are scared. We don't know what's going on. People are worried about their economic future. It's not appropriate. So what we did very quickly was pull back on our traditional spending and our product spending and said, "We're going to do this IG Live series and offer people just a moment of optimism to uplift in their day." So everyday at 5:01, we did a mini-concert, until we got to May 20th, which is the birthday of the blue jean, where we did a full day of programing.

Then, if that wasn't all hard enough, the protests of the death of George Floyd and those before him — Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, the list go on and on — shined a light on the racial inequality, which, of course, was always here, but there were those of us who could operate and maybe not have to think about it all the time. For us in that moment, there was community giving and donations, but we had already consistently been doing that. It had to be about more than that.

We turned the light inward and we looked at ourselves and we said, "For all the progressive values that we represent and all the equality that we've fought for, we haven't done enough in this area." We recently published our racial demographic for the U.S., with a specific eye towards Black employees and the underrepresentation there. We tried very hard not to sugar coat it in any way. We're not where we need to be, we know that. We offered up a plan and some solutions to get us to where we need to be. We need to reflect the population that we serve. It will make us a better business and it's the right thing to do, period. We're on a journey to get there.

[After] that announcement, we also did another series of IG Live events that were about validating Black voices in the community. Many of them we work with — they're part of our community giving or Levi Strauss Foundation giving. Some of them we don't work with, but are people we admire. The point really was to give the space for our fans to hear these voices, not to drive the conversation or intercede in the conversation. I don't have a strategy or a philosophy, but I do fight pretty hard to do what I think is the right thing. Hopefully we're on that path.

A fire has been lit. Not just in my belly, but in our entire leadership team. We are not going to not deliver the commitments we made. I promise you. I said to the employees in the company, "We have to earn your trust. So, you don't have to believe me yet, but check back with me in six months and then check back with me in a year and I promise you we will make progress."

For me, it's really personal. I'm an executive sponsor of our Black employee group. I spend a lot of time with the Black employees, in corporate in particular, and I try to listen and respond. I try to act. I feel like in many ways on the leadership team, I have to represent that perspective, which is totally valid. I try to bring them into the meetings as well, so they can represent their own perspective. They don't need me, the white lady savior always speaking for them.

As you mentioned, this isn't the first time Levi's has taken a stance on something. Do you ever see negative consequences as a public company speaking out on issues that some feel are controversial?

We do, absolutely. The best example is many years ago, we defunded the Boy Scouts when the Boy Scouts said you can't be gay and be a scout leader. We've been longstanding supporters of the LGBTQ+ community, so for us, it was the right decision. Not only did we face backlash, our business suffered in the near term. But we felt it was the right thing to do.

Even today, our stance on gun-violence prevention gets a lot of pushback in social and letter-writing campaigns. There's certainly a group of people in America that thinks it's saying that we're against the Second Amendment, which we have not ever said. So that upsets people and that's fine, they can express that. But we understood [that] when we took this stance.

What would you say has maybe been the most challenging point in your career? Or a major hurdle that you've had to overcome that sticks out in your mind?

I give the younger people this advice: I think you have to be a little bit flexible and fluid in what comes next. Be open to all kinds of opportunities. When I was a U.S. marketing director, I had my heart set on this one job, to be VP of marketing, and I wasn't getting it. The powers that be did not think that I could do it yet, and that was the only job I wanted. It was like banging my head against the wall and I was so just devastated because I saw myself qualified, and I don't think I probably was. But that doesn't matter. Then I opened up to different possibilities — that's when I took a step to the left instead of up, and went into strategy and learned so much. I think ultimately, that accelerated my learning and my experience and enabled me to be better at this job.

So, don't get so stuck on one path. That was a barrier for me. I think the other barrier is — this may be more true for women — finding the power of my own voice and not being afraid to speak up. For me, my book coming out in 2008 was a real turning point because I kept it a secret from work, because I didn't want anyone to think that I wasn't committed. I was afraid that if I was being considered for a promotion, perhaps they'd say, "Oh, she wants to be a writer, so let's pick that other guy." The same way women talk about how they didn't talk about having kids [at work]. I didn't talk about my life outside of work. I didn't want there to be any mistake about my commitment. But then the book came out and I was on "Good Morning America," so it wasn't possible to keep it a secret — and it had the opposite effect, which was, I think people saw me in the workplace as more creative and more assertive and more capable. It freed me to just use my voice more. I think that's been a process over the last 10 or 12 years.

It's scary to speak up when you think no one agrees with you. It's not that I don't still get nervous, but I don't hesitate even if I am anymore. There's been this merging of being this athlete advocate and being very outspoken in that world and then finding my voice inside the company as well and not being afraid to use it. I think that was a barrier for me, probably because of my childhood, having the obedience pounded into me. My team would probably laugh at this now, because I have a big mouth. But I really was terrified. I was taught that if you speak up, you're a trouble maker and you're not going to get picked for the team. That was my entire childhood.

How did you logistically find the time to write a book? I'm sure a lot of people want to do that but aren't sure when to literally sit down and write.

When I had this idea that I was going to write it, it was 2006. It was almost like a fever dream: I knew where it ended, I knew the whole structure in my head. It was sort of a weird experience because any moment I had — and I had two small children at the time — I just sat and tried to go as fast as my brain was going, which I don't think is a typical writing experience because, believe me, I tried to sit down and write another book since, and I've not been able to. It just poured out of me.

But I'd get up super early before my kids got up. I'd go to bed super late. I'd sacrifice sleep, essentially, to get it done. I had set a goal for myself that I'd write 1,000 words a day, and that quickly became 2,000. You get better and faster as you write more. But it flew out of my fingers in about three months. Then I sent it to a few people — one friend who's a novelist and my brother, who's a writer. They were like, "Yeah, it's a book," which I didn't expect. I expected them to say it was a mess. They had a few suggestions and I worked on it.

It took me a while to get an agent, but the agent sold it very quickly. But yeah, I just worked in the wee hours of the morning and I gave up sleep for quite a while. I don't know if that's very good advice to someone. Probably not so good for their wellbeing. But it was better for me to get it out than not get it out.

What would you say has been the most rewarding moment in your career so far?

I think for Levis', some of my proudest moments are the community-oriented programs we've been able to do. We have a program called the Levi's Music Project, which aims to reintroduce music education into public schools and community centers. The very first one we did in 2015, with Alicia Keys at a high school in New York called Edward R. Murrow. We had her show up as a surprise to the kids. I just cried the whole time. It was so meaningful to these kids. I found out recently one of the kids has actually gotten a recording contract with a major label.

Then, just professionally and creatively, having this film come out is obviously a dream. I mean, I made a short film back in 2004 that's no good. But I made it. I said at that moment, "This is a story that needs to be told and it's going to be told in a bigger way." It took me 16 years, but here we are.

Looking to the future, do you intend to follow through with writing more books or getting more involved in film?

I definitely intend to write another a book or two. Now I have four kids, which makes it more difficult, and a more demanding job, which makes it even more difficult. I'm waiting for that lightning moment like I had last time, that it hits me and I just pour it out. My understanding, from writer friends I know, is that that is unlikely to happen. So I need to push past that and get to the discipline part of sitting down and actually writing it. I usually do what I say I'm going to do.

Is there any other advice you would you give to someone who's looking for a career in fashion or marketing?

Get out there and do the work. Work in retail. It helps you. Talk to people. Get out there. Write. Keep a blog. Just do it. Take a step. Don't wait for that perfect opportunity. You can learn something with every single job you take. If I hadn't taken that first job at FCB, which I did hesitantly... It was always more important for me to take a step forward and do something than to do nothing. I think too often we do nothing waiting for the perfect opportunity, whereas doing something carries you forward.

For a young person, there are a million internships. We have a great internship program. We had so many incredible students from schools across the country, everywhere from Stanford to HBCU's and Berkeley. We hire most of the interns. There's a ton of those kind of programs across the country.

We're introducing a program that allows the stores, our distribution centers, to be a pipeline into corporate. Some companies already had that. That will help us dramatically increase our diversity at corporate because we have a lot more diversity in our retail stores and our DC's than we have in corporate.

People always ask me, "Do I need to study [my field] at college?" I didn't — I studied political science, so that has nothing to do with anything. My advice is always: I don't think you need to. I think college is a time to learn how to think. So go do that. Take the opportunity to read books and learn how to think and apply that to get practical learning in other ways.

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.