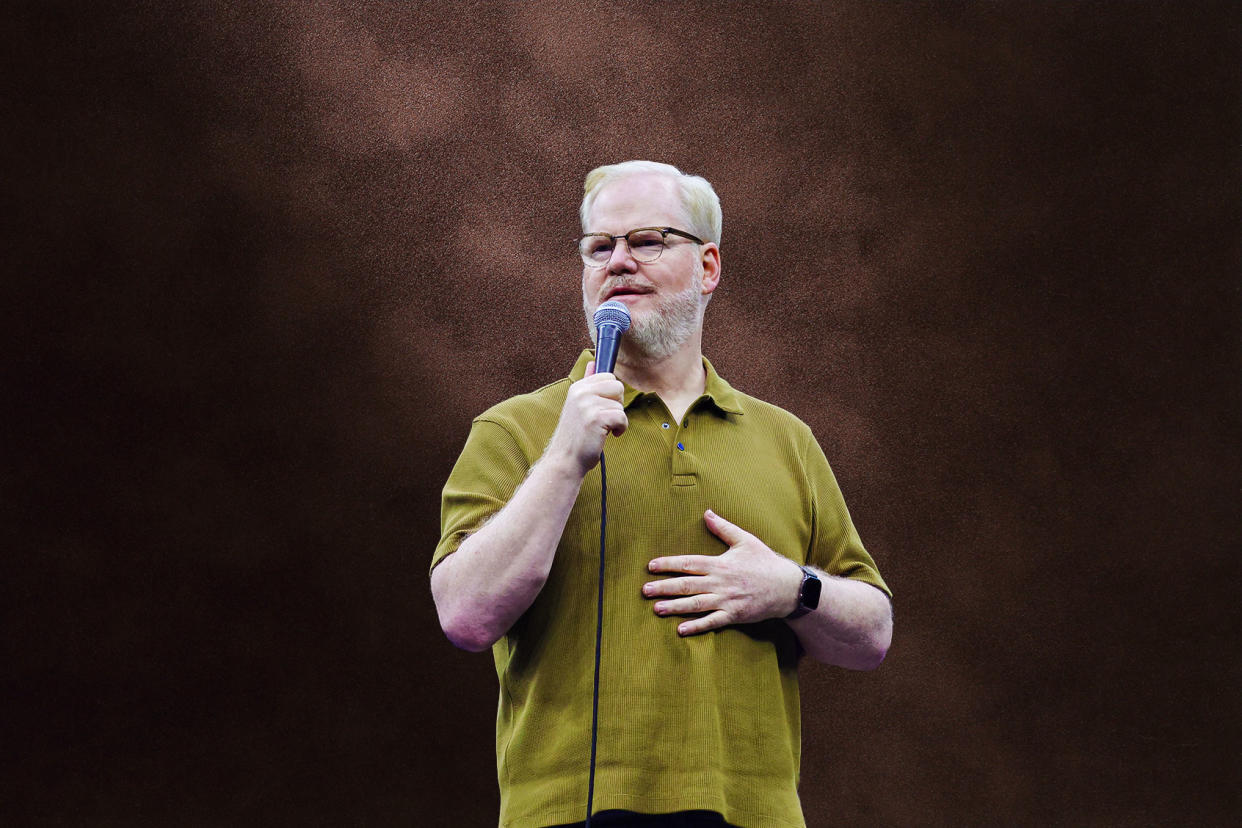

Jim Gaffigan on making darker jokes in today's divided America: "It's a decent vehicle for comedy"

"We have to acknowledge some of the chaos that exists and the fear that exists," says Jim Gaffigan. "If we're not a little bit cynical, we're living in a little bit of denial." Wait, the Hot Pockets guy says what?

Over his over two-decade-long career and 10 stand-up specials, Gaffigan has gained a reputation as a "clean" comic, the guy who ruminates about bacon and the challenges of raising his brood of five kids. And it's accurate to say that those aspects of his sensibility are as true as they ever have been. But the comic, actor and author is also, like all of us, a person who's lived through some rough times, and wants to talk about it.

In his new Prime Video special, "Dark Pale," (which he wrote and directed and the New York Times calls his "best yet") Gaffigan remains funny as hell, taking umbrage with family life and hot air balloons. And he also talks about death. "We have PTSD," he told me on "Salon Talks." "We've all lost someone, whether it's through the pandemic or just in everyday life."

Longtime fans of Gaffigan know that a touch of dread has always been part of his worldview. And over the past few years, his evolution has taken his observations in plenty of new places — even if some critics haven't always recognized the whole picture. "In one special," he recalled, "I had five minutes on cancer, and people were like, 'He's still clean. He talks about food.'"

But while there are plenty of other aspects to Gaffigan's comedy than his measured Midwestern pace and jokes about fast food, he also knows the label that matters the most to him. "The entertainment industry is perception," he says. "The only adjective that really matters with stand-up is 'funny.'" Watch Jim Gaffigan's "Salon Talks" episode here.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

You talk in this special about death, funerals and some really dark stuff. What has it been like going back out there with this particular special?

The audience has obviously all gone through the same stuff. We all have had this emotional development where we wanted to talk about the pandemic, didn't want to hear about the pandemic, [were] frightened of it coming back. We all occasionally will hear about somebody getting COVID, and you're like, "Wait a minute." We have PTSD. We've all lost someone, whether it's through the pandemic or just in everyday life.

I feel as though there's a maturity there. Initially, people were just ecstatic to get out. My relationship with audiences is that there is the value of time. My ticket prices aren't that high anyway, but if people are giving me two hours on a Friday night, it better be worth those two hours, because we don't have time. When people walk out, I definitely want them to be like, "All right, that was worth it," because I'm the same way. When I'm disappointed by a movie, it's not that it was 14 or 16 bucks – it's that, "Oh man, that's my night."

Every special that you've done is its own moment in your life, family and career. What was the story that you wanted this one to tell?

Some of it is that nihilism is pervasive and maybe it's necessary for how we process today, because we have to acknowledge some of the chaos that exists and the fear that exists. If we're not a little bit cynical, we're living in a little bit of denial. That's where I see the world. In a parallel way, my comedy specials, my children were younger and now three-fifths of them are teenagers, and it's a nightmare. Do you know what I mean? It's really hard.

I know exactly what you mean. That is the word.

When you have young kids, either people don't tell you how hard it is with teenagers or you don't hear it because changing a diaper is like a cakewalk compared to waiting for a teenager to come home on a Saturday night.

There are bookshelves galore about how to parent up to the age of two, and there are no books about how to parent an adult.

There are no books on how to parent a kid that's been exposed to social media for six years.

Speaking of your parenting, you took your son with you on this tour. Jack, who, if I'm not mistaken, gave you the title of your first book, "Dad Is Fat," as well.

Yes, he did.

Tell me what that experience was like, and why you wanted to do this.

We did two separate weeks of tour. Some of it was that I want to spend time with my son. Some of it is also, he's expressed interest in stand-up. He is also one of the funniest people I know. You can tell a kid something or you can have them experience it. I wanted him to understand the preparation that goes into stand-up and also that there is something involved in it that is outside of just saying the most irreverent thing.

We did two week-long tours, and I think he learned it. But there is also something of human beings, we learn things and then we have to relearn them. He is very funny, he could definitely do it for a living. But there is something about the entertainment industry, the amount of humiliation and rejection you have to consume. Not everyone has that appetite. I think he might, but I also know that when I was 17, I've probably had 10 different lives since then. I feel like every five years I'm a different person.

For a long time you have been known as the "clean comic." You're the clean guy, you're the Catholic guy, you're the guy with a lot of kids. Yet I've watched your stuff, and you talk about death, diarrhea and your politics and beliefs. That runs, I think in some ways, contrary to that image. What's that about?

The entertainment industry is perception. In a lot of ways you don't have control over that, and in a lot of ways, it's none of your business. I remember initially being resistant to being known as the clean comedian, just because the only adjective that really matters with stand-up is "funny." Like in one special, I had five minutes on cancer, and people were like, "He's still clean. He talks about food."

You don't have control over what people will take away or what people will assign to you. It's a strange thing where I go with the flow. I've had numerous acting roles yet with every acting project, people are always like, "What's it like to be an actor?" These are intelligent people that have seen my IMDb page, but in their perception, I am a guy who only tells jokes about food. It doesn't bother me, and it's not an indication of someone not doing their research. It's just the perception.

Has there been a shift in the last couple of years when you have been a little more vocal about where you stand on certain issues? Or does your audience know you? Do they know that that's what you're going to do?

There's two answers to this. One, I do like the idea of, not thinning the herd, but purifying it a little bit. So if I say something that the setup is like, "We all agree on gay rights," and then I just do another observation, if that initial statement turns people off, it's like, that's fine.

On the other side of it, I do feel like the relationship I have with people that come to my shows is that they don't necessarily have to agree with everything as long as I'm not preachy. In "Dark Pale," I have stuff about global warming. When you travel around the country doing material, you can get a different sense with how an audience is taking in a premise. There are times when I'm talking about global warming, someone in the audience will be like, "All right, I don't necessarily agree with this premise, but I think you're funny and I want to see your take on this." In this divided America that we live in, we don't necessarily agree with everything, but it's a decent vehicle for comedy.

I'm always so fascinated with the way that you use the voice of the audience in your act, and you've been doing that for a long time. That voice has changed over the years. What is that voice now? How do you tap into that? What do we sound like to you now?

I'm this slow-talking midwesterner, and I was in New York City in the early '90s, before YouTube or satellite radio. Stand-up was closer to combat than what it is now. The audience wasn't as educated on what stand-up is or even how to consume it. So it was a tool of just always speaking for the audience if they had a judgment, because I'm this white bread guy. If I went on stage, they'd be like, "Does this guy know how white bread he is?" It's like if I bring it up, not only does it communicate self-awareness, it's a shared like-mindedness.

I don't want to lean on it, but also, it adds an element of an additional point of view, which is always fun. So if my point of view on a topic is pro it, then the inside voice can be against it. It also is just a great way of defusing a situation. I did it when I was a teenager. People just feel at ease where it's like, "All right, at least he knows he's late."

You've been talking about your family as long as you've had one, which is over 20 years now. Your kids are getting older now, they're transitioning into adulthood. How do you balance now how you talk about them? Do they get any veto power in what you say? How do you create good boundaries so that they feel safe?

It's this moving target because you never want to go full Kardashian. We live in such a voyeuristic, exhibitionist era that if you are not revealing some of yourself, you're not going to develop a relationship with the audience. My general approach on parenting is that if a parent is complaining, it means they're involved, and I'm not hiding anything from my children.

It is hyperbole, but it's weird because it's one of those things where a 10-year-old's view on having a father that's a comedian is different from a 17-year-old's. My dad was a small town banker. I am aware of it. I would talk about my children as opposed to a specific individual. If it was a specific individual, and if I'm highlighting their behavior, it would be something that they would like. It would be them standing up to authority in an empowering way as opposed to the behavior of making them embarrassed. My kids are more worried about a photograph being posted.

It is interesting because we do live in this day and age where some of their peers are really into comedy, or their families are really into comedy, and they might have an awareness. And then some kids are not into comedy and it would never come up. Comedy is something that's enjoyed by everyone so it doesn't hit a particular type of kid. It could be an athlete, it could be someone that really excels in academics, and not that those are mutually exclusive.

Plus you live in New York City — all the kids' parents have Emmys.

I'll run into my kids' friends when I'm doing shows because they're going on stage. It's a strange thing in New York City. Or I'll be auditioning for something and I'll see some kid's parent. So New York City's a small world.

Watch more

"Salon Talks" with comedians