The Fascinating Story of How Lilly Pulitzer Came to Be

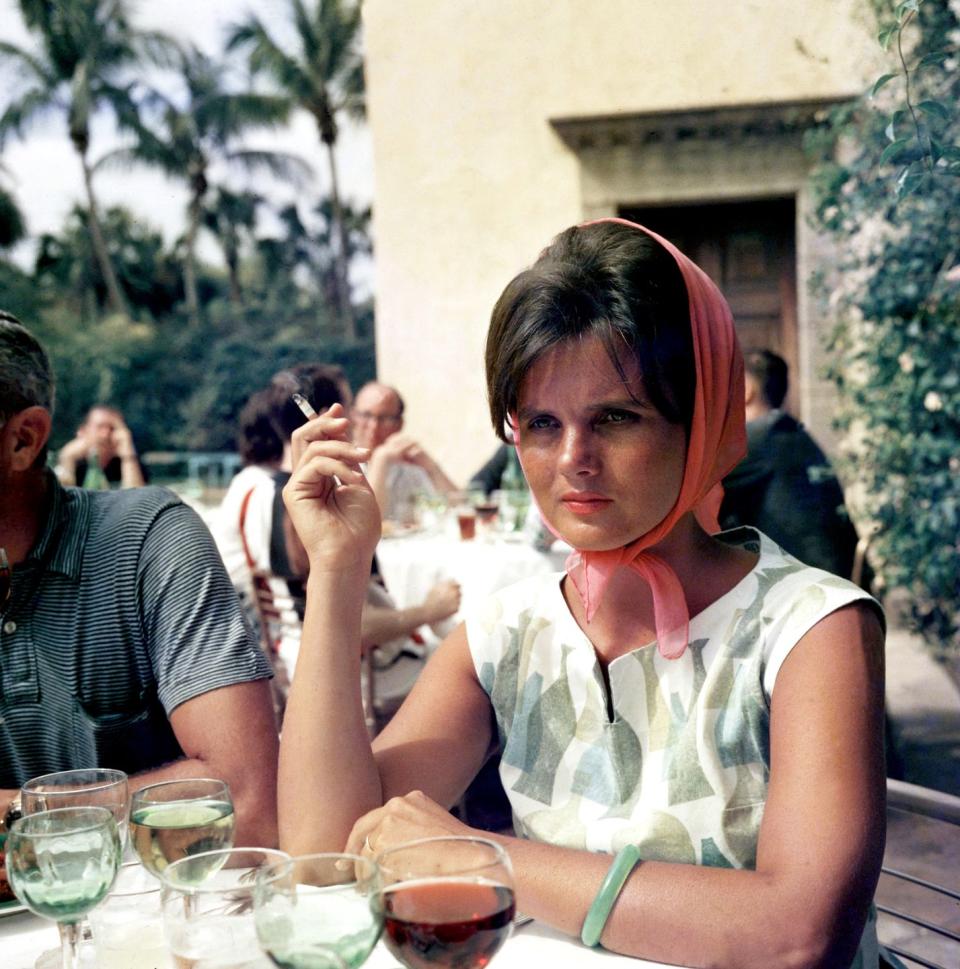

If you happened to find yourself strolling along Palm Beach's tony Worth Avenue on a warm day in the mid-1950s, it wouldn’t be unusual to encounter a small rhesus monkey. The monkey (Goony, as he was known) would likely be perched on the shoulder of a young, barefoot woman named Lillian McKim Pulitzer, who—despite what her dirty toes and unkempt hair might imply—was a local Palm Beach socialite with a privileged pedigree.

For many people, the name Lilly Pulitzer conjures up images of an affluent, prim-and-proper woman on her way to the beach; not a free-spirited bohemian who loved martinis, loathed underwear (she rarely wore it), and toted her pet monkey around town. But Lilly Pulitzer had a penchant for surprising people, and the story of how she launched her namesake brand is no different: it began in the confines of a psychiatric hospital.

The year was 1958 and Pulitzer, a just-married heiress and new mom, felt she was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. ("In hindsight, I think it was really and truly postpartum [depression]," Lilly’s daughter Liza said in a phone interview.)

Not knowing what was wrong with her, Lilly did what any wealthy twenty-something would do—she checked herself into a mental health facility. ("In the old days, we used to call it Bloomingdale's," she joked.) "I had never had a responsibility in my life," she said in a 1994 W magazine interview. "I couldn't button my shoes or do my own pigtails...All I had ever had to do was get to my tennis lesson or ride my pony."

Pulitzer spent several months in treatment and eventually received a startling diagnosis from the doctor. "There's nothing the matter with you," she recalled the physician saying. "You just need something to do." And so, she decided to open a juice stand.

As the story goes, Lilly thought up her now-iconic shift dress while squeezing oranges from her husband's orchard. The design would be printed to hide the juice stains, thick enough to go commando, and unfitted, to keep comfortable and cool in the Florida heat.

She asked a seamstress to create a sample, and before long, she was out of the juice business and into the dress business. "I asked my husband if we could put a few of my dresses in [his fruit shop], about 12 or 15," Lilly told the Palm Beach Post in 1964. "He said 'No—80!' I said, 'You're out of your mind.'"

But they were an instant hit, even before Lilly developed a partnership with Key West Hand Prints, a screen-printing shop, which would become essential in establishing Lilly Pulitzer's iconic vibrant aesthetic.

"The first Lillys were made from fabrics I'd buy in the dime stores in West Palm Beach," she said in a 1971 interview in the Palm Beach Post. "We were a real shock to everyone. People thought the Lilly dress was a fad that would last about two years...We just picked up steam and kept going."

The clothes sold because they were unlike anything else on the market.

"They were the antithesis of what most women were wearing at the time. In the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, women were corseting themselves to fit the clothes. They were wearing heavily constructed longline bras, panty girdles, full slips, stockings, stiletto heels—it was that Mad Men look, and Lilly would have none of that," said Steven Stolman, who not only curated the brand’s 50th Anniversary Retrospective, and worked on the revival collection of Lilly Pulitzer in the ‘90s, but also had a personal friendship with the woman herself. (Stolman is a regular contributor to TownandCountryMag.com).

"Remember, Lilly was not a little lady. She had a big personality, a huge heart, and an appetite for life. She loved good food and she loved a good cocktail," he said.

Key to the success of the business was Lilly’s network of society women, both in Palm Beach and back in New York, but none of whom influenced the brand’s popularity quite like Jackie Kennedy.

After the first lady was photographed in Capri wearing a polka-dot Lilly Pulitzer shift in 1962, the business “took off like a zingo,” to quote the dressmaker herself. And by February of 1963, Lilly was the one being featured in magazines; the popularity of her clothes, which by that point were being sold in boutiques nationwide, had warranted her a Life spread of her own.

“Palm Beach has long been the place where styles were set. But it was not the place where styles were made. A good-looking young brunette with a good head for business has changed all that,” opened the article, titled "A Barefoot Tycoon Makes Lillies Bloom."

"Almost single-handedly Lilly Pulitzer has created a dress fad that is sweeping the country—a design she calls the 'Lilly,'" it continued. The story, which featured Wendy Vanderbilt wearing Lilly’s styles, also highlighted the designer’s atypical lifestyle. "Lilly Pulitzer represents a departure not only from the way Palm Beach dresses, but also from the way Palm Beach lives."

Lilly's independent spirit wasn't a product of her time in Florida; rather, she was always an original thinker, despite growing up in the somewhat rigid world of old-money society.

Lillian Lee McKim was born in Roslyn, New York in November of 1931 (or somewhere thereabouts; Lilly was always a bit coy about her age). The great-granddaughter of Standard Oil partner Jabez A. Bostwick, she wanted for nothing and attended the famed Miss Porter's School right between Lee and Jackie Bouvier.

Following school, she eschewed a traditional debutante coming out, instead joining the Frontier Nurse Service. She later met and married Peter Pulitzer, of the Pulitzer Prize family, in a whirlwind romance.

"I was about 21. We eloped in Baltimore and flew down to Palm Beach,” she recalled in a W Magazine interview. “When I called home, Peter got on the phone and said, 'Mr. McKim, I've just married your daughter.' All Pappy said was, 'Which one?'''

Despite their spontaneous elopement, the pair settled down in Palm Beach—which even pre-Trump was a resort destination for the wealthy where few lived full-time—and shortly after, started a family.

"She was a very, very good mother. Because she was born into wealth, she had the luxury of being eccentric... She didn’t have the typical worries that a lot of people have of paying the mortgage, but she was also very sensitive to inequality," Stolman said.

"She was incredibly liberal and progressive, and I think she struggled fitting into what is essentially a mean old Republican town."

The ‘60s and ‘70s brought Lilly professional triumphs, but also personal troubles. In 1969, she and Peter split up. She married Enrique Rousseau, a Cuban émigré, not long after the divorce was finalized, but she didn’t change her company’s name. ("My parents remained the best of friends," Liza once told the New York Times, "but the love of her life was Enrique.")

Lilly launched a line of children’s clothes and another for juniors, and delved into menswear. Even the Duke of Windsor was a fan; according to a 1968 Suzy column he owned a pair of the brand's "bathing trunks."

Throughout it all, Lilly maintained her signature bright, printed aesthetic. "'The Lilly' doesn't really follow trends," she said in April of 1978. "It has become a kind of classic after all these years, kind of on the order of a Chanel suit. It doesn't change, you can always recognize one."

She kept designing until 1984, when what the Times describes as "a series of ill-timed expansions, combined with changing tastes toward more minimal designs" led the company to file for bankruptcy.

"Mom was never a businesswoman, but she was incredibly creative," her daughter Liza said. "She never set out to become a recognizable designer. Her whole being was a free spirit. She was happiest when when she was designing. The pressures that she felt most were knowing how to run a business." And so, when it got to be too much, she closed the doors.

The company was revived in the '90s, by Sugartown Worldwide, Inc, a company that owned the brand until 2010, when it was sold to Oxford Industries for $60 million. Steven Stolman was a designer for that initial relaunch collection; Lilly served as a creative consultant.

"The label had two lives," Stolman said. "There was Lilly Pulitzer when Lilly herself had her hand on the clothes, and then there was the Lilly Pulitzer when the label became the property of a corporate entity. Those clothes—the post-corporate ownership clothes—are very, very different than the original clothes. It’s as night and day as Coco Chanel’s designs for Chanel versus Karl Lagerfeld’s."

In the '90s, the brand had to adapt both to modern taste, but also to corporate ownership, and department store ambitions.

"Clothes had gotten far more body conscious by 1993," Stolman said. "Stretch fabrics had become the norm for women. Women wanted clothes that had a flexible fit, and the problem with 100 percent cotton poplin is that it is not flexible, so we needed to add further tailoring to make the dresses fit in a way that flattered women more. "

Despite clinging to its Palm Beach heritage, it wasn’t the same; it couldn't be, if it wanted to scale—a local business being run out of a small Miami factory simply isn't suited for mass-market retail goals.

And so the modern Lilly corporation looked to the future—moving their headquarters to Pennsylvania (the company now operates out of a pastel building nicknamed "The Pink Palace" in King of Prussia, and keeps a small design studio in Palm Beach), trying out trends like electric-neon prints, and launching collaborations with fellow giants like Target and Starbucks—all the while keeping an eye on the ethos of its namesake.

"Lilly herself was always looking forward and that’s how we approach our design process—forward-looking with a strong heritage," Lilly Pulitzer Executive Vice President of Product Design and Development Mira Fain wrote via email. She pointed out that modern silhouettes and innovative fabrics, like the brand's new UPF line (which helps block UV rays) are just as much a part of the current iteration of the iconic Lilly shift as classic dressmaker details and hand-painted prints.

"Through the years, women and girls of all ages have worn the brand for the sunniest days of their lives and made the happiest memories in Lilly—they’ve connected on a deeper level with the brand; they’ve connected emotionally," CEO Michelle Kelly added, emphasizing the multi-generational nature of the company.

Lilly Pulitzer's legions of hyper-engaged fans on social media (835,000 followers on Instagram and counting) serve as evidence to that connection, and prove an authentic heritage can be an appealing marketing tactic, especially when trying to capture customers of all ages.

But perhaps the strongest testament to the brand that Lilly Pulitzer created lies in the entrepreneur's last name.

"Growing up, people always asked if we were any relation to the Pulitzer Prize," Liza recalled.

And now? "People ask if Lilly was my mom."

Photo Research by Jenny Newman and Design by Michael Stillwell

You Might Also Like