The King’s favourite architect, Léon Krier: ‘Europe has, in 70 years, never built a decent building’

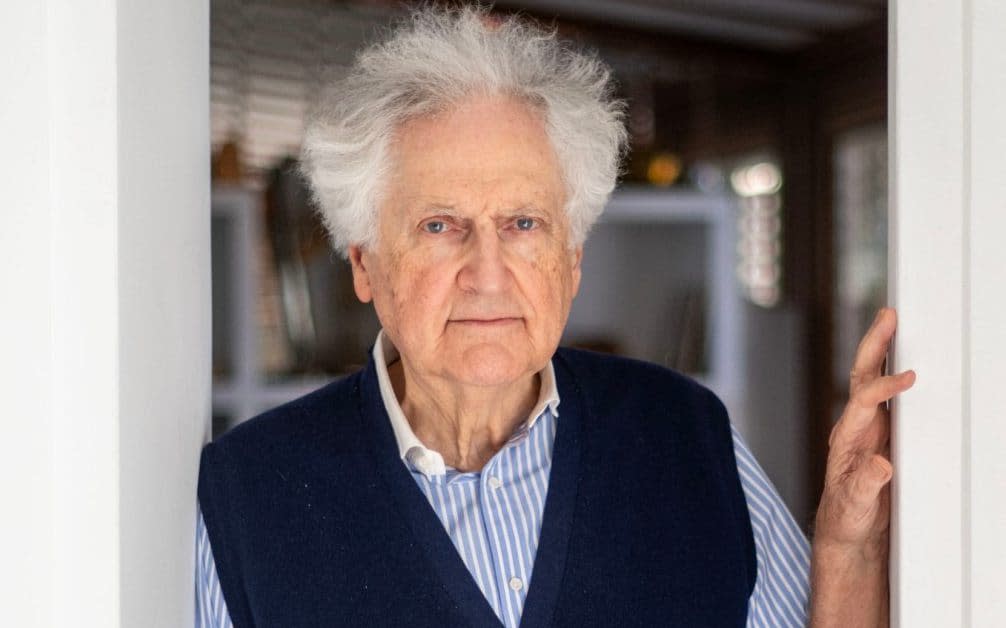

He is regarded as the King’s favourite architect; the man who built the model town of Poundbury in Dorset; who finds modernism and its high-rises repulsive. For more than half a century, Léon Krier has been pushing for towns and cities to be built on a human scale, drawing on traditional architecture and classical models.

And in recent years, the ideas for which he and the former Prince of Wales were once so roundly mocked, prizing community and sustainability over density, have become central to the discussion about how to build in the 21st century. “Well, they are not our ideas,” he says, when we meet in Palma, Mallorca. “They represent thousands of years of good experience. Whatever was bad about the past, architecture was not the bad part.”

The 77-year-old applies a withering gaze to present-day London and the look-at-me skyscrapers jostling on its skyline, subject of a damning comment piece recently in the New York Times, which suggested that planners nod through buildings by trophy architects, with no thought about height or appearance. “I travelled across London on the bus recently, from Greenwich to Mayfair, to see what’s going up,” he tells me – “the only decent thing about new building is the scaffolding – once they come down the truth is revealed.”

He’s an aesthete, with a Wildean way of delivering a put-down, in a deep, rich timbre. One could imagine encountering him in one of Europe’s great cities on the Grand Tour. He grew up in Luxembourg, and lives there, he says, “but I need the sun”. He and his partner Irene Pérez-Porro first met in Palma 50 years ago; their beautiful apartment by the cathedral looks out over the ocean. A grand piano greets you; the dark wood shelves are filled with books and music scores.

Yet this committed traditionalist is also seen as a guiding spirit of New Urbanism. The much-talked-about concept of 15-minute cities owes much to his ideas about urban planning, in which all basic amenities – work, shopping, healthcare, education and leisure – can be easily reached on foot or by bicycle. But the 15-minute cities concept has been dogged by a conspiracy theory that it is part of an anti-car plot.

“Within two or three generations, cars will probably be a very rare occurrence,” he says. “And it’s very difficult for people to understand that cars are not going to stay with us forever – electric cars even less.”

So does he think Sadiq Khan’s ULEZ scheme to keep cars out of London is a good idea? “What would be the alternative – let them all in? These towns were not built for cars.” We need to start planning now, he believes, for a future beyond fossil fuels, because they are a finite resource – their end could lead to the complete collapse of modern society, he believes. “The wars we have now are about the realisation of who is going to control the remaining fossil fuel and uranium and lithium.”

Of course, Krier is still most widely known for his association with the King. He was never an arch royalist, he says; he had regarded Luxembourg’s grand ducal family as faintly ridiculous as a youth, and paid no attention to the wedding of Charles and Diana in 1981. But when he heard the Prince’s famous 1984 speech at Hampton Court, in which he railed against the proposed extension to the National Gallery as “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”, Krier says it showed “not only sensitivity, but intelligence – and clearly, that he cares”.

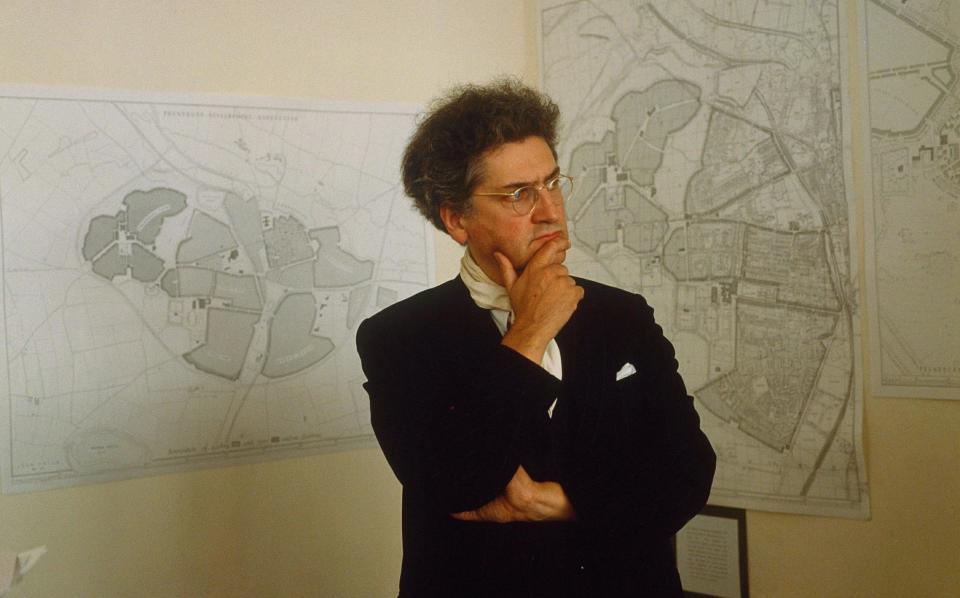

Krier met the Prince for the first time three years later, when he exhibited his original plans for the redevelopment of Spitalfields (he’d withdrawn when financiers insisted he build higher than four storeys). “The Prince said, ‘I know all about it. Let’s talk.’ He asked me to become his advisor on architecture and town planning, and so we met in strange places at night, you know, two o’clock in the morning in some Russian princess’s house, because we were not meant to be seen to be involved in schemes.”

Krier excited the wrath of City of London planners when he inveighed against the scheme for Paternoster Square near St Paul’s cathedral. The Prince would also double down on his earlier remarks, suggesting that modern architects had desecrated St Paul’s and done more damage to the London skyline than the Luftwaffe. His interventions, Krier recalls, prompted the architect of ‘The Gherkin’ and the Millennium Bridge, Norman Foster, to suggest, “‘we have to cut the oxygen of publicity to the Prince of Wales’.”

Krier takes no credit for influencing the Prince before their closer association. “Clearly it was intuitive, because when he officially visited these horrible housing estates or the National Theatre or Queen Elizabeth Hall…” He repeats the name in horror. “How can she accept such a horrible building to be called in her name? It’s so ugly, in detail and in whole… at the least, she should be revolted.”

Their high-profile allegiance, though, would soon bear fruit – several months later, he was appointed to do Poundbury. Krier’s vision of a traditional town built on Duchy of Cornwall land adjacent to Dorchester, was not embraced by the estate’s other planning advisors, who “colluded against it really dramatically”. Contracts had already been drafted for one of Britain’s biggest supermarket chains to build on Duchy land. “I said, ‘it’s a million wasted, it’s the wrong investment.’ [These chains] know how to plant a hypermarket in a geography, it’s a military operation, a colonial project.”

Krier wanted a mixed-use development with its own shops and cafes and a small supermarket. And what of those who see its ordered streets as a sterile, patrician exercise on the part of the King? “We live in a society which has hierarchies which are no longer proud of themselves,” he says, adding that it was astonishing to see how much one person could achieve, because “immediately, it worked” as a town.

Krier grew up with a brother and two sisters; his father was a tailor, his mother a talented pianist. They had survived the Nazi occupation of Luxembourg. “My father’s company was forced by the Germans to make uniforms for the Russia campaign,” he says, “and if production slacked, the commandant would say, ‘Little tailor, you know what will happen to you and your family if you don’t speed up.’”

Sandwiched between Belgium, France and the hated Germans, Luxembourgians looked towards Paris, Krier says, but when he visited, he was disappointed with it compared to his own capital city, which was “small but had grandeur”; it would be a lifelong influence. As a youth, Krier served for a time in the army, before studying architecture in Stuttgart, where his brother Rob Krier was working. The professors there disregarded his work. One even said: “This is the kind of thing we did in the Third Reich.”

It foreshadowed an argument that would later damage his career, when he published a book on Albert Speer, the German neoclassical architect who became the Nazi minister of armaments. “I lost everything,” he says. The whispering campaign that labelled him a Nazi led to Krier abandoning his own design for the National Gallery extension, and leaving for Rome. “Absurdly, it’s always traditional architecture that is associated with Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini,” Krier says. “But Hitler also built gigantic modernist buildings – why were they not forbidden?”

Krier found an escape route, without finishing his degree, when he sent some of his drawings to the British architect James Stirling. Moving to his London offices, though, Krier found his ideas increasingly at odds with the celebrated modernist. “He had just done the Florey Building in Oxford, which is an absolute horror. I worked on it, doing the tiles, but in the office we knew it was not good. I mean, technically and artistically, it’s the end of the line.”

It is also, one should point out, now Grade II* listed, but a lesser fate awaited Stirling’s futuristic concrete housing development for 6,000 residents in Runcorn town centre, which finally convinced Krier he had to leave. He spoke out at a company meeting. “I said, ‘I think we are building slums’,” he tells me. When the whole development, completed in 1976, was marked for demolition in the late 1980s, Stirling stopped by to see Krier at home. “I said, Jim, do you think they are wrong?” He slips into a gruff impression of the man after whom Britain’s most prestigious architecture prize is named. “They are wrong,” he barks. There is fondness there, though. “Stirling was nice to me,” he says. “I mean, he was a very difficult man, not easy to talk to, but several times in my life, he did things which helped me enormously.”

On leaving the practice, Krier began teaching at the Architectural Association and Royal College of Art, where he famously coined a phrase that has become associated with him: “I don’t build because I am an architect.” Zaha Hadid was one of his students, still to find her creative identity at the time but always first there in class, he recalled later. Her fire station in Weil-am-Rhein, Germany, that he visited when he went to see Frank Gehry’s Vitra Museum, was “better than I thought,” he concedes. Gehry’s masterpiece in Bilbao, too, he thought “more interesting, spatially, especially inside” than he had imagined. But he comes back to the cost of the grand statements of the starchitect era: “That kind of excessive cost is helping corrupt politicians to circulate money without control. For me, it’s architecture that has a lot to do with corruption. If it had produced great architecture like the Vatican, I would say, I didn’t care. But it’s junk.”

London, he suggests, attracts too much building. “All the growth goes in the South of England. And why?” he asks. “The North is very nice, too.” Instead of adding another million people to London, he insists, “why not build a series of new towns, which is combined with small-scale agriculture.”

Of course, one of the reasons people build densely in cities is because of planning restrictions elsewhere. Does Krier advocate the use of greenfield sites? He describes an argument he had when presenting a proposal for a town like Poundbury – “but a bit smaller” – to be built outside Malton in North Yorkshire. “It was opposed by the locals,” he says. “People came to me shouting, ‘You want to take down the trees. I have birds singing in my yard, you want to take away the birds.’ I said, ‘But Madam, before you lived there you had birds exactly where you stand. Should we stop now? The birds will still be around but we will make a new town, which will be more attractive than the old town – because it’s not attractive.’ And she said, ‘That’s offensive.’” The middle-classes are apt to see anyone who wants to build near them as a “class enemy”, he suggests.

Meanwhile, modernism has so dominated architectural thinking of the post-war era, he believes, that anyone who doesn’t accept its orthodoxy is shouted down. Yet he rejects it almost completely. “I recently met the Italian lady, Benedetta Tagliabue, who designed the extension to the Scottish Parliament,” he says. “I had only known the first part, but the second part is so bad, you think, ‘She must really hate the Scottish people.’”

As for the EU and its earlier iterations, he says, all its public architecture is “barbaric”. “Europe has, in 70 years, never built a decent building.” Well, perhaps one, the 1952 Court of Justice of the European Union in Luxembourg City, which has since been “renovated” by Dominique Perrault. “It was a nice building. Now it’s three skyscrapers in slabs of glass. He messed it up.

Of his own works, he says, only the Krier House in Florida is 100 per cent as he planned it. And his earlier statement that he didn’t build because his ideas would be corrupted? “I was right.” And Poundbury? The resulting model town, he says, is closer to his vision than he ever thought it would be, “because I was never optimistic”. The King remains a friend. They stay in contact, “but he can only come once a year unofficially to see Poundbury.” Work has just started on the final element of the town, which, Krier declares, “will be the best”. Is it, I wonder, only for the wealthy – a criticism that has been levelled, too, at the model town he designed in Guatemala City, Cayalá? People who attack it on that basis are “hypocrites”, he says. “When [Norman] Foster builds for the rich and the super-rich and the mega-rich nobody complains.”