La Quinta resident represented Frank Sinatra from Rat Pack glory days through mafia allegations

La Quinta resident Jim Mahoney’s first client upon becoming an MGM movie publicist in 1947 was Clark Gable, the “Gone With the Wind” star known as the King of Hollywood.

After that, his career grew.

His client list after forming his own public relations firm in 1959 included Dean Martin, Bob Hope, Judy Garland, the Rolling Stones, U2, Bob Dylan, Johnny Carson, Jack Nicholson and Steve McQueen. He went from representing Sonny and Cher to handling the City of Palm Springs after Sonny Bono was elected mayor in 1988. Bono used Mahoney to attract national attention for his fledgling Palm Springs International Film Festival.

But his most important client was Frank Sinatra, the longtime Palm Springs and Rancho Mirage resident who died at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles 25 years ago May 14.

Mahoney, 95, met Sinatra at his lowest ebb, as his wife, film siren Ava Gardner, was leaving him. He represented Sinatra through the heights of the Rat Pack when Sinatra built a small empire with his own film production company, his own recording studio and his own casino while recording such standards as “Strangers in the Night,” “Something Stupid” (with daughter Nancy Sinatra), “It Was A Very Good Year” and “Fly Me to the Moon.” He was making classic films such as the original “Ocean’s Eleven,” “The Manchurian Candidate” and “None But the Brave.”

Through Sinatra, Mahoney met John F. Kennedy while he was running for president and needing advice on how to win Richard Nixon’s home state of California. He met Chicago mob boss Sam Giacana and defended Sinatra from Mafia allegations. He was with Sinatra when kidnappers sought a ransom for Frank Sinatra Jr. In fact, he took the kidnappers’ call.

Mahoney learned how to mitigate crises about volatile personalities such as Sinatra from fabled MGM publicist Howard Strickling.

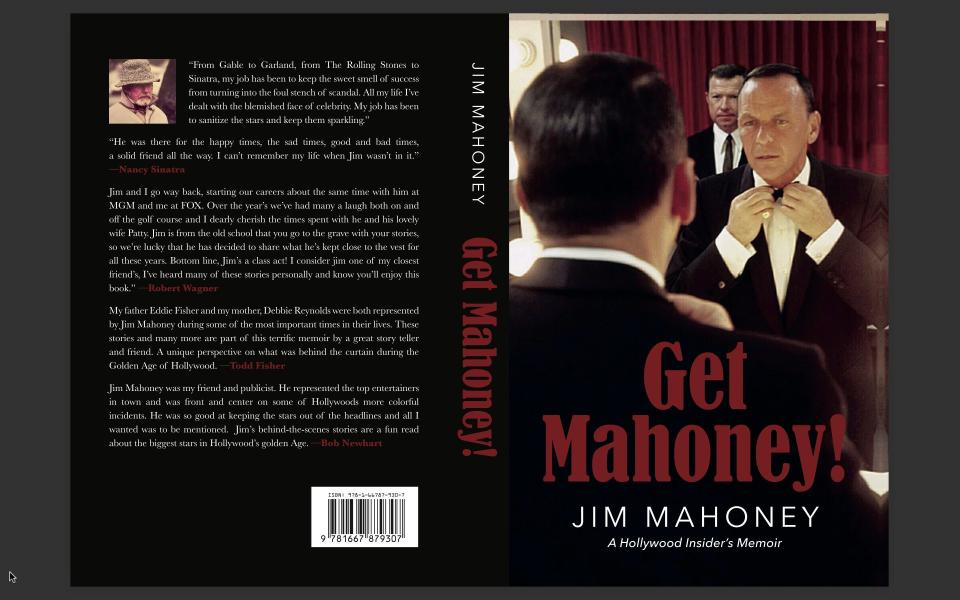

“My job,” he said in a promo for his new book, “Get Mahoney! A Hollywood Insider’s Memoir,” “was to keep the sweet smell of success from turning into the foul stench of scandal.”

Strickling taught Mahoney old Hollywood tricks of mastering coverups — by lying and paying bribes to hide crises ranging from stars’ sexual misconduct to suicide attempts. If Strickling couldn’t mitigate a PR problem with MGM money, he or studio boss Louis B. Mayer would assign Eddie Mannix, a Ray Donovan-type “fixer,” to take care of it.

Strickling’s Rule No. 1 was: Keep yourself out of the story. He once told Mahoney how an MGM publicist tried to refute a doctor’s report that Garland had cut her throat by calling it, “just a scratch.” When asked where the cut was, the publicist pointed to his neck and a photographer snapped a picture. The next day, a headline proclaimed, “MGM publicity man shows where Judy slit her throat.”

Mahoney discussed how his PR career preceded cultural shifts such as the MeToo movement and cancel culture in a wide-ranging interview at his home with his son, Sean, next to him to help him manage an injury from a fall. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Howard Strickling told you a publicist should keep himself out of the story. So why did you write this book?

A lot of people said, “Why don’t you write a book?” I was on a plane to Europe and I got a pencil and paper and started writing. It’s been an unbelievable journey. No one else has ever crossed that path.

Were you taking notes all that time?

Never. I never took notes.

The book chronicles an era when bad behavior was swept under the carpet. Today we’re taught to be transparent. If a star is accused of misconduct, we protect the accuser. It offers great cultural context, but is self-published. Did you have trouble pitching it to publishers?

I went to the William Morris Agency. The problem is, when I submitted the book 10 years ago, more often than not the publisher would assign the reviewing process to some kid that was an hour-and-a-half out of college. They didn’t know Alan Ladd. They didn’t know Gary Cooper. I was fortunate to handle some real characters. Lee Marvin, George C. Scott, Fred Astaire.

You call Steve McQueen your most difficult client. But Marvin did things that would land him in jail today.

He was one hell of a guy. Got his ass shot off in World War II (severing his sciatic nerve). He made (21) landings in the South Pacific, which is mind-boggling. They put him on a hospital ship and he never lived it down that he didn’t get back to support his troops (most of whom were killed in the Battle of Saipan). The reason he did a lot of drinking was because he thought he let his troops down.

I understand survivor’s guilt. But, did his war hero status give him a pass for bad behavior?

Sure. He did crazy things. He had guns and he’d go out and shoot cans (in Malibu). He got (drunk) one night and drove to Camp Pendleton to re-enlist.

You wrote of getting an early morning call from a cop who said Marvin put a woman in the hospital. You replied, “Well, he’s in Mass right now.”

They don’t teach that anymore.

That’s my point. They teach you not to say that today. But did you empathize with him because of what he’d been through?

Big time.

You’re wearing a Korean War veteran’s hat. I know you belittle your actions in Korea, but, can you say what you did to earn a medal?

Well, I was serving in a dangerous zone in Korea. My job was to call in artillery fire if the enemy got too close. On one occasion, I was on the front line. I had a Jeep driver, but we got lost (behind enemy lines). Luckily we got out of there and performed the mission successfully. That’s why they presented me with the Bronze Star.

How did the studio people act when you returned?

You’d think I was (World War II hero) Audie Murphy. I was writing a gossip column for the Herald Express for a couple months. My boss, Harrison Carroll, got seriously ill (and) in those months, I got to know everybody of importance at every studio. Debbie Reynolds was a good friend. She was doing a movie with Frank Sinatra and I was having lunch with the press agent. Debbie comes by and says, “Are you coming down to the set?” I said, “Your set is closed. Sinatra doesn’t want any press.” She said, “Bull. I want to talk to you. Get your ass down to the set after lunch.” So I went down there and all of a sudden, everything got church silent. “Doesn’t he know Sinatra’s working here?” Debbie sees me and says, “Jimmy, this is Frank Sinatra. Frank, this is Jimmy Mahoney. He’s a good friend of mine. I don’t want you to give him any shit.” That was my introduction to Sinatra. Throughout the period I was writing that column, I was welcome to any of his sets. He’d invite me to dinner. One night he says to me, “How long are you going to stay in that hokey business?” I said, “Til something better comes along.” He says, “It just did. I want you to work for me.” But, backing up, Debbie was under the impression I was some kind of war hero. I wasn’t. There were 10,000 guys who had more dangerous missions than me.

That speaks to the eras’ cultural differences. In my generation, guys returning from Vietnam weren’t considered heroes. Veterans from previous wars were given greater allowances for bad behavior. Did that make an impression on your clients, like Sinatra and Lee Marvin.

It made a big impression.

Your book is titled “Get Mahoney” because clients would call you whenever there was trouble. You said the first three rules of crisis management were: Money talks, pay big and pay fast, and keep it out of the press. Did you learn that from Strickling?

Strickling and Eddie Mannix, who was an executive at MGM, and Whitey Hendry, the (MGM) police chief. They had more policemen at MGM than in most small communities. If there was a problem of any kind, Strickling was there and Eddie Mannix was there. More often than not, they’d take me with them, which is how I learned.

Did Hendry have such clout that his word was respected as an official police report?

Hendry had a relationship with the police chiefs ― in Glendale and definitely Palm Springs. He was there for many years, and money, money, money speaks.

Did he give money to cops?

(There were) giveaways that came their way. Trips to Europe when they were filming there. Whoever the cop was, he got a nice vacation. That went on all the time.

Why do you say, “definitely Palm Springs”?

There were a lot of people connected to MGM that had homes down here.

You say in your book that things were swept under the carpet. You also allege Clark Gable killed a jaywalking pedestrian. It later became known that he impregnated (actress) Loretta Young.

Among others.

So, what was the process? When you got the news, what would you do first?

Tell Strickling.

And Strickling would talk to the victim?

Whoever he needed to talk to. If it was a teenager that was abused, he’d go to the teenager’s home and write a check.

Today that’s done with lawyers. They’ll offer compensation in exchange for an NDA. Did you and Strickling do a precursor to that?

Yes.

How did “the fixer” come into play? If Strickling couldn’t take care of a problem with money, he’d go to Mannix?

I think it was more Louis B. Mayer. He was, like you say, the fixer. If a guy’s contract was coming up for renewal and they wanted to make sure the deal was made, they’d call in Mannix and say, “Do something for this guy. We want to keep him.”

Was he “muscle”?

I’m sure he was. I never got into that, but it was there.

Do you know the story of how Eddie Mannix’s wife died in the desert in 1937? She was at The Dunes casino in Cathedral City with its owner, Al Wertheimer, of Detroit’s Purple Gang. They left after midnight and he drove off a road. The car rolled and she died. He was seriously injured. The Desert Sun reported that Mannix’s wife was at The Dunes with a bridge group and Wertheimer volunteered to take her home.

A perfect example of Strickling and Eddie Mannix.

You tell the story of (“Shane” star) Alan Ladd trying to shoot himself to death in the ’50s.

He missed.

Right. But that’s another case of how things were handled differently then. The studio’s priority was to keep it out of the press. Today, you’d be concerned about his mental health. Did you think, “We need to get this guy help?” or was that a lesser priority?

Alan was past his prime. He wasn’t getting the roles and he shot himself. Later, he overdosed in Palm Springs. Killed himself. (Riverside County Coroner James S. Bird Jr. ruled it an accidental death from a “high level of alcohol” plus Seconal, Librium and Sparine, according to a Feb. 4, 1964 Desert Sun story).

His wife was a PR person trained in that culture. That’s what I mean by the differences between the old era and today.

If you were under contract to MGM, and the same with the other studios, you never got sick. You never got pregnant. You were perfect. That’s why you never saw anything about Gable.

But even the doctor who treated Ladd seemed trained to perpetuate the myth. He volunteered to say it was an accidental shooting, right?

Also (with) the accidental overdose.

Do you think that studio culture enabled people like Harvey Weinstein to think they could get away with abusive behavior?

No question about it.

Let’s get back to Sinatra. Would you put him on your list of difficult clients?

No. He never caused me any problems really, until he went to Australia and called the press parasites and $2 hookers.

Rudin was your antagonist (telling Sinatra that Mahoney should have accompanied him to Australia to protect him on that 1974 tour. Sinatra fired Mahoney afterwards).

Rudin never liked me. He said I was giving Frank away.

For charity events?

I did influence him on that.

Let’s talk about the incident at the Polo Lounge (in the Beverly Hilton Hotel) where Frank, Dean Martin and Jilly Rizzo were with two Black women…

I wasn’t there.

No, but you were called to handle that. Did you talk to the waiters and bartenders to line up their stories? (The tale goes that Sinatra and Martin were confronted by a man who complained of their loudness. After returning to his seat, he allegedly uttered the “N word” and a brawl ensued. Rizzo reportedly broke the man’s skull, but no charges were filed).

They didn’t need to be educated. They were well educated in the process (of what to do) if there’s a problem in the restaurant. There was a problem and it was messy for a while.

But they knew to prioritize Frank and Dean because show biz was paramount in L.A.?

Yeah.

You start the book with an amazing story about how Sinatra summoned you to Lake Tahoe after Frank Sinatra Jr. was kidnapped.

He asked Rudin to get me on a plane. I was there to handle the press, feed them some material. It was a national incident. I was designated as the phone guy.

When you got back-to-back calls from (Chicago mob boss) Sam Giancana and (FBI Director) J. Edgar Hoover, did it surprise you that Frank chose to talk to Giancana first, making you put Hoover on hold?

Yeah. Frank got a kick out of that. He had the good guys and the bad guys working together.

You knew Giancana. How would you describe him?

He knew me because I represented Frank. I knew him from weeks, or months before (the kidnapping). Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra and I were going to Indiana to start a movie and, at the last minute, there was a change of plans. We were to stop in Chicago and go to a birthday party for some important friend. The important friend was Momo (Giancana).

You write about the Sinatra and Bob Hope golf tournaments (Hope allegedly refused to host the Palm Springs Classic unless Sinatra ended his 1963 celebrity pro-am because he didn’t think the desert was big enough for two pro-ams). Did they really have a rivalry?

It was amusing. Occasionally Sinatra would say, “How come I don’t get the kind of press that Bob Hope does?” And Hope would say, “How come I don’t get press like Sinatra?” I said (to Hope), “What do you want?” He said, “Why don’t you get me on a stamp?” I said, “You have to die for that.” “Let’s go on to another subject.” There was never any love between them. They got along, but there were bumps along the way. Hope was putting together a Sunday night Chrysler special and he had an idea with this manager. “Let’s get Frank Sinatra and pay him the $50,000 we’d have to pay for two or three people.” And Sinatra agreed. Word got back to Detroit that Frank Sinatra was the star of the special and the bigwigs at Chrysler didn’t like Sinatra as a spokesman for Chrysler.

Because of his alleged Mafia associations?

Could be, yeah. They wanted out of the deal and Mickey Rudin told Frank. Frank said, “They owe me $50,000.” He took the $50,000 and sent it to charity.

You also had Jack Nicholson as a client.

I didn’t have much to do with him. My partner, Paul Wasserman, handled some of these people — The Rolling Stones, U2. Who else, Sean?

Sean: Linda Ronstadt, Neil Diamond, Bob Dylan. Wasso did movies and rock 'n' roll.

How would you compare Wasso’s clients to your older clients in terms of keeping their “excesses” quiet? Was it as difficult to mask their bad behavior?

Sean has probably heard more (stories about) those people.

Sean: I’ve heard a few. U2 hired Wasserman because he handled the Stones. They wanted the guy who handled the biggest band in the world. Wasso handled some of the biggest rock 'n' roll bands of all time. But you handled some of the biggest singers of all time.

I handled Andy Williams, Tony Bennett, Vic Damone, Paul Anka, Eddie Fisher.

Wasso got sucked into the lifestyle of some guys he represented. You didn’t get into the crazy lifestyles of Marvin and George C. Scott. What was the difference?

I remember asking George why he drank. He said, “Do you know what I did in the Army?” “Not a clue.” He said, “Have you ever been to Arlington Cemetery?” I said, “Yeah. We buried Lee Marvin there.” He said, “Well, that’s what I did for two years. I buried people. That’s when I started drinking.”

If you were active today, would you handle your clients differently?

I’d be in a different business.

“Get Mahoney! A Hollywood Insider’s Memoir,” is available at getmahoney.com and online book sites.

Bruce Fessier is a freelance journalist and former Desert Sun editor-writer. Contact him at [email protected] and follow him at facebook.com/bruce.fessier and instagram.com/bfessier.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Frank Sinatra's publicist through Rat Pack days, alleged scandals