Should Lael Wilcox’s Arizona Trail FKT Come with an Asterisk?

This article originally appeared on Outside

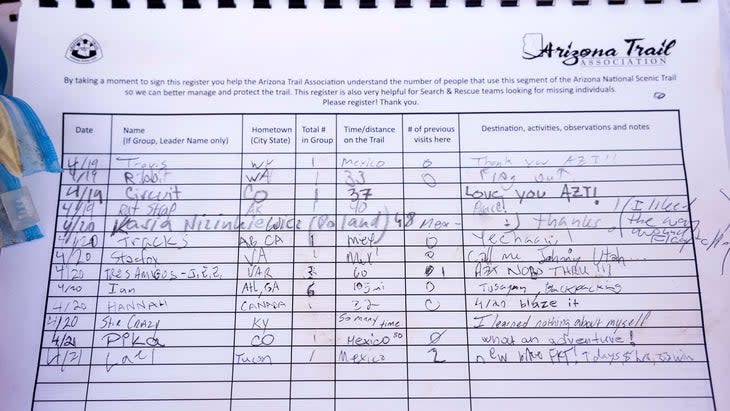

On April 21, 34-year-old bikepacker Lael Wilcox pedaled into the Stateline Campground on the border between Arizona and Utah. She had just finished the Arizona Trail, an 827-mile route, in record time: 9 days, 8 hours, and 23 minutes, which bested the existing record by more than two hours.

Wilcox, a rising star in the niche cycling discipline of ultradistance cycling, was thrilled. Her days on-trail had been grueling: she averaged just under 90 miles a day on a rocky, technical route that involved ample hike-a-bike. She carried all her own supplies, found water and food along the way, and pedaled without a pacer or support crew. But she was not alone. Her wife, photojournalist Rue Kaladyte, and a friend, Sean Randolph, drove along the route and hiked or biked out to Wilcox about twice a day to shoot videos and photos of her effort. They took pains not to provide her with any mechanical assistance or to hand her any food or drink, as a way to preserve the ride's status as being self-supported.

But when Wilcox finished the ride and announced her time online, John Schilling, the race director for the Arizona Trail Race, an annual mass-start event in late October, called into question whether Wilcox had followed the rules of self-supported racing.

"Rules," he posted on Instagram. "The AZTR has them and enforces them. Rule #2 explicitly states no media crews & no record will be acknowledged if a media crew is used. There's also a visitation rule which states excessive use may result in relegation. Unfortunately this too occurred over the entire 800 miles. Lael's finish time...will be noted, but not recognized as the self-supported record for violating the above rules." According to Schilling, Wilcox's time would be listed in official race records, but with an asterisk next to it, because having Randolph and Kaladyte following her conferred emotional support.

Schilling had already informed Kaladyte and Wilcox midride that Kaladyte's photography was at odds with the race rules, and Wilcox decided to continue with her initial approach and accept the asterisk--it seemed the situation was resolved. Then Wilcox and the cycling website The Radavist both made Instagram posts announcing the new FKT without adding an asterisk, prompting Schilling's announcement. And after his initial caption, Schilling added a comment that seemed to accuse Wilcox of cheating, and the conversation soured.

"You can disagree all you want, but the media crew was clearly doing more than simply documenting the ride," he wrote. "Just call it what it is: a supported FKT. The AZTR doesn't keep records for supported rides and doesn't have plans to do so. I hope she had a fantastic time and got everything she set out to accomplish, but don't call it a self-supported record. It's not."

Schilling says he was referring to excessive visitation, which is at odds with unsupported efforts. Some bikepackers argue that having the daily emotional support of a loved one--even just the reassurance that there's a person keeping tabs on you-- boosts a rider's performance on the trail in an unfair way. "That's the one thing I regret. I should have been more clear," he says. "I wasn't accusing Rue of giving her food or water. It was a 100 percent clean run."

The controversy sparked a fierce online discussion. One camp argued that rules for the AZTR were posted online, and so if Wilcox wants to set records on this route, she should abide by them. But others questioned whether one or two people shooting occasional photos and videos really constituted a crew, and whether this differed from Schilling's own practice of meeting riders out on the trail. Still others wondered whether these rules were being selectively enforced. The debate has highlighted the challenges facing the growing sport, including the ethics of self-supported riding and how the community treats its most prominent, successful athletes.

Even at a relaxed pace, riding the Arizona Trail is unforgiving. It starts at the Mexico border in the Miller Peak Wilderness and points riders northward into a mix of technical singletrack and dirt roads. It covers huge expanses of waterless, remote desert, traverses high mountain ranges, and includes a 21-mile hike across the Grand Canyon. The national park forbids mountain biking, so riders must carry their bicycles on their backs without letting the wheels touch the ground, even for a quick nap. The ride ends at the Utah-Arizona border between the small towns of Fredonia and Page.

Singletrack isn't Wilcox's comfort zone--she's a gravel rider, primarily--and she knows firsthand how many things can go wrong during a bikepacking effort. She began dabbling in the sport just over a decade ago and soon began putting down blisteringly fast times and getting what, in a niche sport, amounted to a lot of attention.

In an episode of the Bikes or Death podcast about the controversy, professional endurance cyclist Sofiane Sehili said of Wilcox, "She's by far the most followed person in this sport. … She's the person that inspires the most people out there, definitely."

Wilcox had tried the route once before, in 2015, during a film project with REI, but problems with asthma forced her to call it off. So she set out with the simple goal of riding to the best of her ability, hoping the FKT was in reach.

"The trail's been on my mind for seven years," Wilcox says. "I didn't know if I could get the record or not, but I really didn't care--the main thing was just finishing it. I wanted a redemption story."

From the outset, Wilcox made great time. Kaladyte posted updates to her Instagram page, and she was on pace for the record. At the Picketpost Campground near Superior, Arizona, about 300 miles in, Schilling--who lives nearby--came out to cheer Wilcox on.

Schilling oversees the AZTR as a volunteer, and he works two day jobs to support his role with the race. The event has no official ties to the Arizona Trail Association, the nonprofit that builds and manages the trail. Schilling's role involves organizing the mass-start event, an annual race held in October. He also tracks individual riders throughout the year and maps and maintains updated GPS data for riders interested in the route. People regularly complete the AZT as a bikepacking route independently of the mass-start event, and Wilcox was riding it as an individual time trial--which involves registering through the race website to get an official SPOT tracker. The race rules are listed on the website, but Wilcox said she hadn't seen them before starting her effort.

Schilling often hikes out to meet folks who are riding the route, take pictures of them for the race's Instagram page, offer them a smile or a high five, and send them on their way. He gave Wilcox a hug, they chatted briefly, and Wilcox set off in search of water--she had run out five hours prior and needed to keep moving.

Kaladyte and Randolph, who was effectively chauffeuring Kaladyte, were also there, along with Josh Weinberg, a journalist who works for The Radavist, a cycling website Wilcox has written for. Wilcox had pitched a first-person story to The Radavist before her ride, and it had agreed to publish her account.

"I don't think that went well," Wilcox says of the meeting with Schilling. Kaladyte and Wilcox alone, with a friend helping drive the car, could maybe be written off as personal media coverage. But the third person, and his affiliation with an official media outlet, could have tipped the scales.

After parting ways, Schilling sent messages to both Kaladyte and Weinberg. To Kaladyte, he wrote:

"Wow!! Lael is Flying!! She's ahead of Chase's pace by 21 hours through Sunflower...I'm ok with what you posted over the first day+ of the ride since you're based out of Tucson. However, I let them know that any further coverage from someone following her is a clear violation of the AZTR Rule #2 re: media coverage. It would negate any record. If Lael calls in with updates or sends along any pics that's fine. I'd love to see her smash it, just please follow the rules." He sent a similar message to Weinberg.

When Kaladyte and Wilcox met up next, they discussed the messages and decided to carry on with their original plan to document the effort.

"I didn't know that there was a new rule for the race--that rule came about in 2019," Wilcox says. "I was like, 'I'm not compromising. We're still just gonna do it, asterisk, whatever. If I'm not considered part of this race that's fine.' The trail exists outside of the race. It's a national scenic trail, it's public, it's free," says Wilcox. "I was like, 'OK, well then, I'm trying for an FKT on the trail, which is awesome.'"

Although Wilcox was racing the trail by herself, there is a mass-start event held on the trail each year. Both standing records for the trail were set during the race in 2021: Chase Edwards set the women's record with a time of 10 days, 18 hours, 59 minutes, and Nate Ginzton set the overall record in 9 days, 10 hours, 44 minutes. These records are kept on the records page of the AZTR website, which also hosts the rules.

"No support crews, this includes pre-arranged camera/media crews," the website reads. "The AZTR views this as support. Feel free to self-document all you like. If you want a camera crew to document your ride, either do it on your own or expect an *, no record times will be noted for media support." On visitation, the rules say only, "Visitation by spectators (friends, family) is OK if they are local to the route, the visit is near town/services and the visit is short. No pacers!"

This rule is not easy to find. To get to this version of the AZTR website, you'll have to follow a link in the bio of an Instagram page with just over 1,300 followers. If you Google-search "Arizona Trail Race bikepack," you'll wind up at an archived, older version of the rules that are nearly identical but say nothing specific about media crews. However, those rules do include lines that read, "The idea being that small forms of support and unfairness do not make much of a difference in the long run, and that we are taking ourselves too seriously if things like innocent spectating and cheering of a racer are prohibited."

Wilcox disputes the proposition that having Kaladyte and others documenting her ride gave her any greater emotional support than she would have received during a race. She also points out that she received emotional support from the people she encountered on the trail.

"I'm not riding in a vacuum. I passed dozens of hikers, and they all knew what I was doing, like a game of telephone across the trail. The rangers in the Grand Canyon were cheering for me as I crossed the river," she says. "It was so cool. Should we try and diminish that? That's so lame. For an FKT? Who cares? This is life!"

FKTs are a surprisingly slippery concept. If you're setting a course record in a race, there are clear rules, an obvious governing body, official times, and at least a few witnesses. But FKTs are often set in time-trial fashion: just an individual rider, runner, skier, or climber alone on a route. For runners, the website FastestKnownTime.com (which is now owned by Outside Inc., the company that also owns this magazine and website) has long served as the official arbiter of these efforts. A small staff of five, along with 15 volunteer "regional editors," evaluate FKT efforts for style and ethics, confirm GPX tracks, and determine whether that effort was valid--and whether it counted as supported (with a crew), unsupported (solo, with no outside help), or self-supported (solo, but with cached supplies). The website has grown to become widely accepted and respected.

"As a team, we acted as interpreters for how the community viewed things," says ultrarunner Peter Bakwin, one of the co-founders of the website Fastestknowntime.com, which tracks the records. "FKT is a culture. And really what we've been doing is trying to figure out, 'What are the cultural norms?' and then put them into writing."

The FastestKnownTime.com crew didn't create a rule about whether media coverage counts as support until last year. The question included too much gray area, Bakwin explains. Once, a cameraman ran alongside a runner for so long that it could have been considered pacing, which felt like an obvious breach of unsupported style, Bakwin says. But then there was the time a media crew was going to shoot a runner from a distance, using long lenses, so that he wouldn't cross paths with them at all--was that OK? Or did just knowing about their presence influence his effort? Another athlete approached FastestKnownTime.com staff with a plan to run unsupported, but with batteries for his camera, which he would use to document himself, stashed along the route. Would that make his run self-supported? Eventually, the FastestKnownTime.com staff opted to ban media from unsupported efforts--but this was after nearly two decades of listening to the community.

"If FKTs are going to be fair for everyone, there have to be clear lines demarcating what constitutes supported, unsupported, and self-supported efforts," Bakwin says. Schilling echoes the importance of rules--they exist to level the playing field.

But the rules around setting a route record in bikepacking are murky. FastestKnownTime.com doesn't keep records for sports other than running and skiing, and the rules that apply there don't align with bikepacking. (For instance, according to FastestKnownTime.com, self-supported refers to a route completed with cached gear and supplies, while cached gear would disqualify a rider from a self-supported record on the AZTR.)

In bikepacking, there isn't yet a widely accepted set of standards, a community-wide definition of a supported or self-supported effort, or a respected jury to turn to when things get muddy. For now, that responsibility falls on individual athletes and race directors (who are typically bikepackers themselves). In the case of the Arizona Trail, that responsibility falls somewhat uncomfortably on Schilling's shoulders, since the route exists independently of the AZTR. Because of his role, he's the closest thing to an authority on the route and how to ride it in good style. But the controversy over Wilcox's result raises questions that the bikepacking community at large will have to answer.

Wilcox does not believe her media team gave her an advantage--if anything, the it was more of a distraction. Sehili, who has ridden with media crews of his own before, agreed in a podcast episode, saying he doesn't think it confers any advantage.

But, he explained, hypothetically it could. Say he get got caught in a storm and worried that pressing on would be unsafe. Knowing there were people ahead who could help him out of a dangerous situation could change his decision-making, he said. Even without an emergency at hand, the idea that someone is waiting for you just ahead could boost morale. The issue is fairness, Sehili explained. "It's very hard to have a level playing field, but we need to do whatever we can to have one," he said. That's why the [personal] media crew that's out there to follow an athlete is something that we need to question."

With an easy smile and a charming, open demeanor, Wilcox is well suited to the modern demands of a professional outdoor athletic career--which involves regularly participating in film and photo projects, posting on social media, and telling her story to an online audience. In a fringe sport like bikepacking, where many of the biggest races don't require an entry fee but also don't offer prize money, there simply isn't a way to support yourself purely as a competitive athlete. High-quality photos and video are key to Wilcox's living.

"I became a sponsored rider through media and storytelling, which totally changed my life," she says. "I used to work in restaurants and bike shops, and now I get to do what I love every single day." In a 2022 interview with Outside, Wilcox repeatedly stressed a desire to share the sport, get people inspired to ride their bikes, and connect with the places a bike can take them. She's still amused, and delighted, at the trajectory of both her career and the sport itself. "I can't believe people actually care about bikepacking! I never thought that would happen," she says.

While the overwhelming response to Wilcox's internet presence is positive--she has almost 100,000 Instagram followers, a huge number for a bikepacking athlete--the backlash she's gotten from some members of the bike community is wrapped up, in part, in the fact that she's sponsored. In an Instagram post, ultra-cyclist Chase Edwards wrote, "Ultra racing is a game of resources. Without a set of standards for racing and record setting, the humans with the most resources will always come out on top."

This isn't the first time Wilcox has faced criticism for having Kaladyte follow her during a bikepacking event. In 2019, in preparation to ride the Tour Divide, an annual self-supported race along the Great Divide mountain-bike route, she asked permission six months prior to the race to have a crew film her ride. Matthew Lee, the unofficial race director, gave her permission, and she moved forward with planning her ride. The plan called for Kaladyte to shoot Wilcox's ride for her sponsor at the time, Pearl Izumi. Two weeks before the race, controversy erupted after critics argued that Kaladyte's presence constituted emotional support, and that her documenting the race violated the spirit of the race, even though filmmakers had previously documented the event. The night before the race, Kaladyte spent three hours talking with Lee, developing an elaborate set of rules involving multiple GPS trackers that would allow her to make the film without interacting with Wilcox.

"Then I get to the race and find out that this guy who is my direct competitor has his own team of three guys following him in a van shooting out the window, and no one said a thing," Wilcox says. "It was insane. I wouldn't jump to this conclusion except that this was such a controlled environment. Everything else is the same except that this is a guy, and he didn't ask for permission. Nobody cared."

Other racers who were angered by Wilcox's filming plan staged a protest at the start of the Tour Divide. One male rider even lost sponsorship after his treatment of Wilcox during the race. She eventually dropped out of the competition, completing the ride on her own.

Wilcox believes that the new media rule for the AZTR was fallout from the Tour Divide debacle, and Schilling confirmed her assumption. After watching the drama unfold in 2019 with the Tour Divide, Schilling says he thought the AZTR needed to have an established rule about media, and he consulted with other race directors in the bikepacking world before penning the rules online to avoid confusion.

"At the end of the day, nobody wants more rules. There should be one rule: do it yourself. But unfortunately it can't be that simple," he says. "The media rule has really nothing to do with media. Which is what a lot of the arguments are about: what does taking a pic have to do with anyone being faster or slower? But the media thing really boils down to an extension of the current visitation rule, which has been in place since 2006. We just wanted to limit human interaction. At the end of the day they're supposed to be solo, self-supported challenges. When you have somebody following you the entire route you're not solo anymore. It doesn't matter if you're not talking to them. It's a visit."

Wilcox accepted the asterisk, and though she didn't include it in her initial Instagram post about her ride, it's clarified at the top of her article on The Radavist. And her time is now listed on the AZTR's website, with a note explaining that she broke the media and excessive visitation rules.

"At this point I've learned if I'm going to make a video project I should do it as a time trial because I don't want to influence the other racers. It's better for me just to do it alone so that we don't have that discussion," she says. "I don't want to take anything away from Chase or Nate or any of the other riders. There's room for all of us to take this on in whatever way we want to. If that takes me out of the running of the official list on the race website, that's fine with me."

Schilling has also accepted the outcome. "There is no villain here and there's not really a right and a wrong, right? It just boils down to communication, and I think there was just a big lack of that," he says. "It just got blown out of proportion by a very vocal and passionate group of fans."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.