A Legendary Gilded Age Mansion in Connecticut Gets a Second Life

Houses of a certain pedigree endure on their own terms. Their owners might best be described as stewards, watching over them for a while. Two hours from Manhattan, in Washington, Connecticut, a discreet redoubt that has long been a summer retreat for New York’s privileged, with Norman Rockwell hills punctuated by weathered stone walls and ample mansions (locals fondly call them “cottages”), there is one such home.

Tucked away off a lush tree-lined road, the Rocks was the personal residence of architect Ehrick Rossiter, who designed scores of crisp, shingled cottages in the early 20th century, shaping the now iconic look of gracious country living in the Northeast. Today only 17 of the country houses Rossiter built in Washington remain, and when one becomes available, aesthetes perk up.

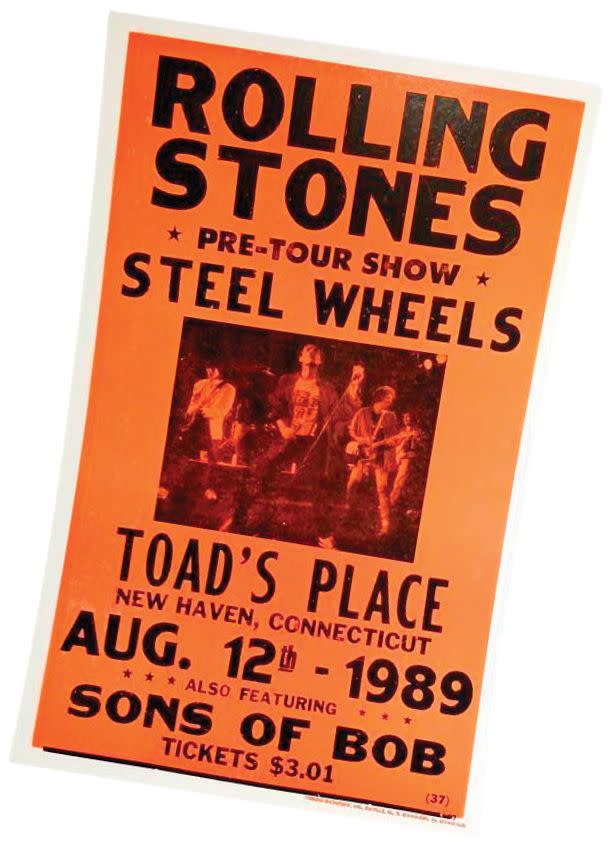

In 1989 the Rolling Stones took over the Mayflower Inn (designed by Rossiter and less than a mile from the Rocks) to rehearse for their Steel Wheels tour, and a year later the art dealer Robert Mnuchin and his wife Adriana bought the inn and its 58 acres and turned it into a luxury retreat. Movie producer Scott Rudin has owned two Rossiter properties, including the Rocks, which is widely considered the jewel in the crown. (He sold it for about $4 million in 2003.) Rossiter used the Rocks to experiment, putting glowing wood shingles on the Queen Anne Revival exterior and tinkering with the intricately carved details inside.

In the Gilded Age he was “rightly held in high regard in Connecticut,” says his biographer, Ann Y. Smith, but he had commissions everywhere from Texas to New York City, where many of his buildings, including the Royalton Hotel, still stand.

The most recent caretakers to heed the siren call of the Rocks are the art collectors Steven and Kathy Guttman, who bought it in 2015. “It was instantly a love affair,” Kathy says. “We didn’t know anyone here. We didn’t have any connection to Washington. We hadn’t even done a historic renovation like this before. But it was something special. When we walked through it we kept saying, through room after room, ‘Oh my gosh. Oh my gosh.’ ”

For all the house’s architectural charms, there were serious issues. “It had become notorious. There were rumors that some of its -owners had divorced or died. A lot of people lived here, and it was worn out, on its last legs,” says interior designer Daniel Sachs, who worked on the project with his partner, the architect Kevin Lindores.

They set about converting the warren of rooms, which had been haphazardly renovated and subdivided over the years, into a proper eight-bedroom, nine--bathroom and maximizing the views of the landscaped gardens and the Shepaug River Valley beyond.

The impressive vista was Rossiter’s doing. The architect bought nearly 150 acres surrounding the property beginning in 1886 to keep the land from being harvested by a lumber company, even though the purchase meant that he and his family had to live for a bit in the carriage house (now the Gutt-mans’ guesthouse). “Those years were seminal for Rossiter—his aesthetic shifted during that time,” Sachs says. “It would have been an entirely different house if he had built it when he had planned.”

Once the renovation was complete, Sachs set about filling it with the Guttmans’ huge collection of Americana farmhouse and midcentury modern furniture and contemporary art. Steven, a former investment banker, is the founder of the luxury art storage company Uovo, which caters to high-level collectors like himself.

“Daniel helped curate what we already had for the house,” Kathy says. “I approached the living room design as a landscape of furniture,” says Sachs, who met Lindores when they were both working for Frank Gehry, Sachs as a furniture designer and sculptor and Lindores as an architect. In the family room an 18th-century American table is paired with French modern Jean Prouvé chairs. In the main stairway, a 1942 Spiral ceiling light by Danish designer Poul Henningsen casts a soft glow; down the hall the library houses a large midcentury French bookcase.

“I saw the bookcase at an Italian design fair about two years ago,” Steven says. “I had no idea what I was going to do with it at the time, but it fits up there perfectly, as if it were made for that spot. When you have things you really love, you eventually find a place for them.”

For all the house’s blue chip touches—Kathy gestures to a drawing by Julian Schnabel and a large sculpture by Olafur Eliasson in the garden on her way to the custom Italian brick pizza oven on the terrace—the couple emphasize that this is a place for living. A third-floor dorm room has four twin beds for their four rambunctious grandchildren. If rainy days limit outdoor play, there’s a screening room for 18 lined with linen velvet and fully stocked for movie nights.

“It was meant to be a summer home,” Kathy says. “But with our family we find ourselves coming up every month.” It seems that, in the afterglow of its first century, long after its heyday as the cynosure of a great architect’s imagination, the Rocks is finally settling down.

This story appears in the February 2020 issue of Town & Country.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like