Life With Father by Jamie Bernstein

This article originally appeared in the August 2008 issue of Town & Country.

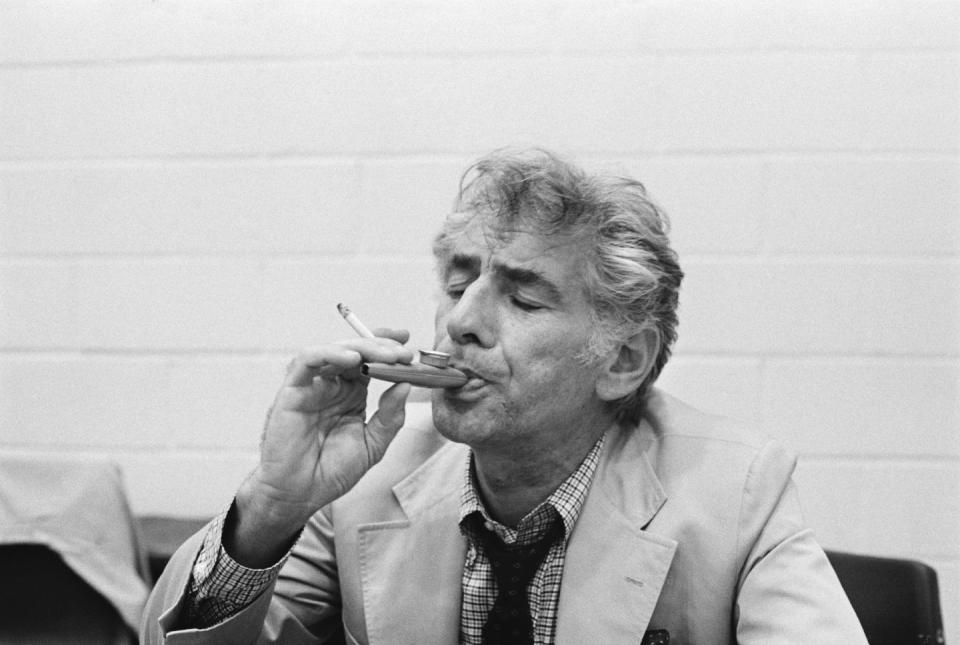

When we were little and shared a room, my brother, Alexander, and I used to drift off to sleep at right angles to each other, listening to the steady waves of laughter, piano playing and singing emanating from our parents and all their witty, noisy friends downstairs. This is what grown-ups did: they drank and smoked and interrupted one another and played raucous word games and sang at the top of their lungs and laughed until they choked. We couldn’t wait to be grown-ups.

Our house was a porous place; people constantly came and went. Fun people, like Betty Comden and Adolph Green, or Mike Nichols (he was really fun). Scary people, like Lillian Hellman. (Our dachshund, Henry, was so alarmed by Lillian that he actually chewed up her photograph.) Glamorous people, like Lauren Bacall and Rudolf Nureyev.

And always, there were our father’s siblings: his sister, Shirley, and brother, Burton, or Uncle BB, as we called him. They made up the original Cheering Lenny Up Brigade. We learned all the tricks from Shirley and BB for teasing a smile or a laugh out of a brooding Daddy—the funny accents, the wordplay, the musical in-jokes ranging from Tchaikovsky to the Drano jingle and, of course, the reverent citations of Yiddish jokes and vaudeville gags that our father himself had taught us.

One of the most important lessons we absorbed from Shirley and BB was how to accompany our father on tour. We’d heard the stories and seen the photos of the antic trio carousing their way across postwar Europe, playing mad games of canasta, buying puppies that peed on their hosts’ carpets and generally pushing the acceptability envelope everywhere they went. We behaved somewhat better, I think, but we understood the basic principle: it was a glorious ride, and one should never take it for granted. We didn’t, and neither did our father.

Going on the road with Daddy and the New York Philharmonic was as good as life got. Everything was first-class—the airplanes, the hotels, the parties and the concerts themselves. It was all very exhausting (and our father never could sleep, in any case), so it fell to us, his traveling companions, to make the most of our shared interstitial spaces: doing crossword puzzles, telling jokes, singing rounds, sharing books and snacks, and making fun of people, including many we should not have been making fun of. Daddy was successful and handsome; our mother, Felicia Montealegre Bernstein, was beautiful, classy and quick of wit; Alexander and I, two years apart, were good buddies when we weren’t squabbling; and we all doted on the baby, Nina. We loved our dogs and our summer house, in Connecticut, and our cavalcade of family and friends.

Until that Friday, November 22, 1963, when I was in sixth grade, that’s how things seemed to me.

On that day, seeing my parents cry for the first time, I felt my world lurch on its foundations. For the next week the grownups still gathered, still smoked and drank—in fact, more than ever—but now it was different. They were distracted and tetchy with us; they stared into space, seeming to be looking at something awful. Maybe being a grown-up wasn’t so much fun after all.

After the assassination, my father decided to dedicate his just-completed third symphony to his beloved John F. Kennedy. The title, Kaddish (as well as the sung text of the symphony), was, appropriately enough, taken from the Jewish prayer of mourning.

My siblings and I were awfully young to absorb the weighty themes and resonances of our father’s Kaddish Symphony. We had the added discomfort of watching our mother declaim in her honeyed, stagy tones the highly melodramatic spoken narration in concert. The music was thorny and unforgiving, with vast atonal wastelands to traverse. By the time the big tunes came along, our fragile attention spans had transmuted into a deep longing for cartoons.

Whatever happened to those bouncy Broadway shows Daddy wrote, whose cast albums spun so merrily on our nursery phonograph? They had all been created before we were born or when we were too little to notice. Now that we were old enough to observe what was going on, it did seem as if our father’s musical works were growing darker. There were failures and stillbirths, as well. We watched as not one but two Broadway shows failed to jell and had to be abandoned. One was an adaptation of Thornton Wilder’s Skin of Our Teeth with the team of Betty Comden and Adolph Green, who had also done both On the Town and Wonderful Town with our father. Another unfinished project, with the West Side Story team of Jerome Robbins and Stephen Sondheim, was based on a play by Bertolt Brecht. The one project that finally made it to the Broadway stage, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, was a calamitous flop, closing after seven performances. We got used to seeing our father slump into melancholy. We understood that it was our family job to jolly him out of his funks. And we were very good at it. Our mother, in particular, was a genius at making our home a lively, restorative place, bursting with friends, flowers and good food. In the summers at our house in Connecticut, nothing made our father happier than sinking his teeth into ear after ear of fresh-picked corn.

Leonard Bernstein was an ingenious recycler. When The Skin of Our Teeth failed, he put one of its loveliest tunes into the second movement of Chichester Psalms, which turned out to be one of his most performed and beloved concert pieces. “Chich” also gave him an opportunity to declare himself on the then-touchy subject of tonality.

Here is part of a poem he wrote in 1965 for the New York Times describing how he spent his sabbatical from the New York Philharmonic:

For hours on end I brooded and

mused

On materiae musicae, used and

abused;

On aspects of unconventionality,

Over the death in our time of

tonality,...

Pieces for nattering, clucking

sopranos

With squadrons of vibraphones,

fleets of pianos

Played with the forearms, the fists

and the palms

—

And then I came up with the

Chichester Psalms....

My youngest child, old-fashioned

and sweet.

And he stands on his own

two tonal feet.

The success of Chich and the pleasure he derived from writing it emboldened my father to embrace tonality on an even grander scale. I was just out of high school when my father began composing Mass (which also absorbed material from the Wilder project). He even put rock music in it! He was always so interested in what young people were thinking about and listening to. Instead of excluding that whole world from his own, as many parents would, he expanded his world to incorporate ours. Sometimes this was embarrassing, but mostly it was exciting.

We watched our father put his whole soul into Mass. He would emerge from his studio at dinnertime, rush to the living room piano and say, “Listen to this!” Then he’d slap down the new pages and raggedly sing and play what he’d just written. Even at our young age, we intuited the vulnerability, the bottomless need he must have felt for reassurance—and so we always told him it was great.

Mass was a cultural big deal because Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis had commissioned my father to write it for the 1971 inauguration of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, in Washington, D.C. We all went down to Washington in the disgusting humidity of early September. We got to stay at the Watergate!

By the time of Mass’s completion, we were waist-deep in the Vietnam War, and we had the very antithesis of John F. Kennedy for a president: Richard Milhous Nixon. For Kennedyphiles like my parents, it must have felt like the most vertiginous fall from grace. Being at the birth of the Kennedy Center was a considerable consolation; if only, my mother said, it didn’t so closely resemble a Kleenex box....

President Nixon declined to attend the Kennedy Center inauguration. He was even advised by the FBI to stay away from the event because there was a “secret message” disguised in Latin, hidden in Mass for the express purpose of embarrassing the president. The secret message? “Dona nobis pacem,” “Give us peace,” just a line in the standard liturgical text of the Catholic Mass. But I guess you couldn’t blame the Nixon administration for squirming.

Mass was criticized from many corners. The Catholic Church was appalled by many aspects of the piece. Music critics objected to the mixing of genres: how could Leonard Bernstein dare to combine a symphony orchestra with a rock band? And to many rock musicians at the time, the rock music seemed, well, square.

By now, the seventies sound of the rock music isn’t so much dated as vintage, and no one blinks an eye if a rock band performs with a symphony orchestra. As for the Catholic Church, it completely got over itself to the point where a few years ago, Pope John Paul II actually requested a performance of Mass at the Vatican! Oh, if only my father had lived long enough to see that happen.

After all the pain and ruckus of Mass, it would have been nice for our father if he could have had a smoother ride on the next project. But with 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the reverse was true.

For the bicentennial, in 1976, he and lyricist Alan Jay Lerner wrote a musical telling the history of a hundred years’ worth of White House residents—the presidents and their wives upstairs as well as successive generations of a family of slaves downstairs. Looking back on it, I think my father and Alan Jay were prescient in identifying racial injustice as the essential seismic fault in American democracy. (It was the very point Barack Obama made in his speech about race in America earlier this year.) But this was not a message Americans felt like hearing in our bicentennial year—much less from two white Jewish guys.

After an early run-through of 1600, my father came home elated. “You know?” he said. “I think this show’s going to be really important.” My heart sank.

It seemed as if the more time went by, the more keenly my father felt that he had to make momentous statements with his music. I think he actually believed that if he tried hard enough, his music could change society for the better. This quixotic goal was a burden to himself as well as to his family.

1600 was such a disastrous failure that the authors could not even bear to make a cast recording. They withdrew the work entirely. We were all very, very sad. And then our mother died of cancer at age fifty-six. My brother and I were in our early twenties; Nina was only fifteen.

Never was it harder, or more crucial, for all of us to find ways to lift our father’s spirits, to say nothing of our own. More and more, we turned to Adolph, who could still make our father laugh.

Maybe the most magical person in Leonard Bernstein’s life was Adolph Green. Nobody on this earth was or will ever be quite like Adolph. He was an utter original: brilliant, zany and devoted. Their friendship dated back to adolescence. Lenny was a counselor at a summer camp where Adolph was conscripted to play the Pirate King in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance. The story goes that Lenny “tested” Adolph at the piano. There was no piece Adolph couldn’t identify—and then, when finally there was one he didn’t recognize and he admitted as much, my father congratulated Adolph on his honesty and confessed he’d composed it himself. They were friends for life. On the day my father died, Adolph came over to the house, held his friend’s hand and repeatedly shouted, “Lenny! Wake up!”

Between those two incidents, Lenny, Adolph and the vivacious, brilliant Betty Comden wrote several Broadway shows, traveled the world, shared family vacations and kept one another laughing for all the decades that passed. There is a wonderful David Levine drawing of my father playing the piano while Adolph, like a demented sprite, capers on the piano lid. That summed up their friendship very well.

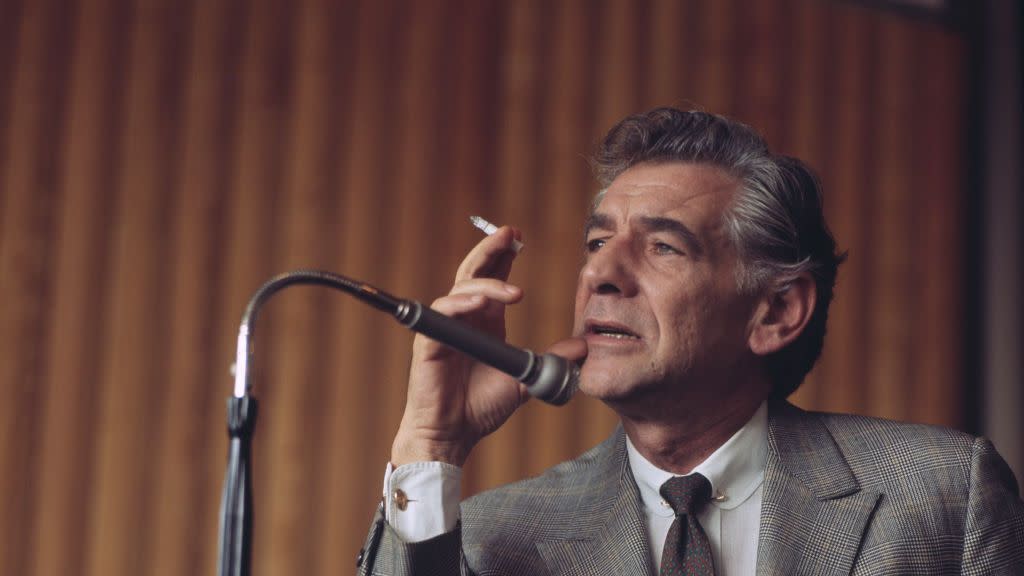

Leonard Bernstein was what my mother mother admiringly called “a man with a motor,” and when he went on the road, that motor went into overdrive. His life became ever more bifurcated between manic conducting tours and glum months at home trying to compose. When he returned from his prodigious global conducting feats with the great orchestras of the world, we’d set about “bringing him down to earth,” reminding him that he was a human being and not a deity. At home, for example, he could not successfully monopolize the dinner-table conversation. When other family members would insist on putting a word in edgewise, he would pound the table and roar with annoyance—but we persisted. Somebody had to. He partly loved being teased and partly didn’t.

There were continuing setbacks in his composing career. A gigantic opera, A Quiet Place, was ambivalently received in 1983. Yet there were still periods of delight. We all accompanied our father to London in 1986, when he conducted a series of command performances of his symphonic works for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. There was endless mirth to share: the frenzied instructions on royal protocol; the major gaffe that ensued when our father was erroneously instructed to strike up “God Save the Queen” before the queen had reached her seat, leaving her standing there like a cigar-store Indian; the mind-boggling vacuity of Prince Philip’s small talk on the receiving line. And then the fun of going home and regaling all our friends with the stories. The best sound in the world was our father’s paroxysmal, wheezy laugh—nearly always followed, alarmingly, by a fit of coughing.

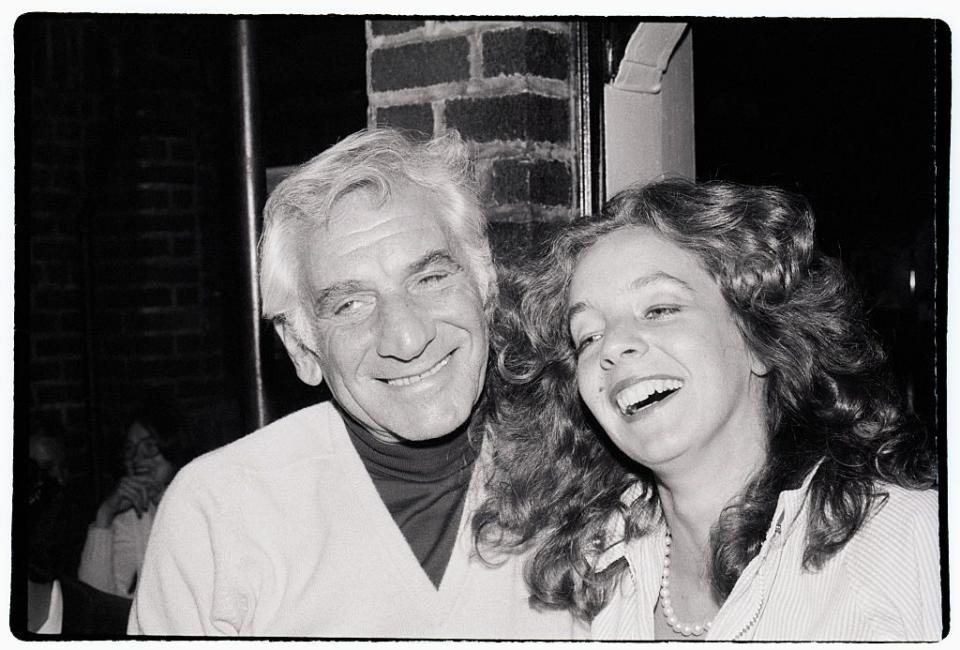

On his seventieth birthday, at Tanglewood, he was so depressed he could hardly get out of bed. He hated turning seventy. He wasn’t a particularly superstitious person, but reaching the Biblical span of threescore and ten really spooked him. (He died two years later.) We had never worked harder to bring some levity to the occasion. We wrote and performed songs for him. I brought his toddler granddaughter, Frankie, over; she could cheer up a train wreck. That evening, at his rented farmhouse near Stockbridge, Massachusetts, we heaped all his birthday presents on the dining-room table and sat down with him to keep him company as he opened them. He sat at the head of the table, disheveled and still in his bathrobe, brightening by the moment as he explored his cornucopia of goodies. While unwrapping the packages, he festooned his ears with the ribbons, the way he always did. Then I knew we’d done our job right, once again.

After my father was gone, what remained was his music. As time goes by, that body of work—so much work!— becomes ever more precious to Nina, Alexander and me. In his ninetieth-birthday year, the three of us are eagerly anticipating the large-scale festival of Bernstein music planned for this fall in an unprecedented collaboration between our father’s two main New York workplaces, Carnegie Hall and the New York Philharmonic. No doubt we’ll annoy our neighbors by singing along (as our father himself invariably did at concerts) at performances of everything from Kaddish to On the Town to Mass. Listening to our father’s music is the next-best thing to getting a hug from him—minus the bone-crushing part.

You Might Also Like