What it's like to grow up with a disease that's kept secret: 'I felt unclean'

Every family has secrets. For Lindsay Ventura, her mother, and her sister, the secret was a disease. At first it was something they didn’t even know they had, but when they were eventually diagnosed, they decided to keep it to themselves for years out of fear they would be stigmatized for it.

The disease was hepatitis C.

In 1990, when Ventura was 3 and her older brother was 5, their father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He was given six months to live. That set things into motion for Ventura’s mother. Despite being healthy and having no symptoms, Ventura’s mom — whose own mother had liver disease — started to worry about her health, knowing she would soon be her kids’ sole parent.

“She was 35 at that time,” says Ventura, whose father passed away in 1991. “The only reason this was on her radar was because [dad] was sick. She just wanted to know she would be around for my brother and I.”

Ventura’s mom went to her doctor to find out if she, too, had liver disease, like her own mother. A blood test revealed she had some form of hepatitis, which the doctor called “non-A/non-B hepatitis.” (The hepatitis C virus wasn’t identified until 1989, so it was still considered a new diagnosis then.)

Her mom eventually remarried and had two more children. A follow-up blood test in 1997 revealed a more accurate diagnosis: Ventura’s mom had hepatitis C. “Even still they knew little about it and said she’d likely die of old age before it was a concern,” notes Ventura. “She had no idea where it had come from. She worked as a physical therapist in burn units, administering wound care, and came in contact with patients’ bodily fluids, and she’s a baby boomer [baby boomers and veterans have higher rates of hepatitis C]. To this day, she doesn’t really know where it came from, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter.”

Ventura’s mom asked the family’s pediatrician if she should have her children tested for hepatitis C since it can be passed from mother to child during childbirth. The doctor said the chances were “minimal,” but her mom decided to have all four children tested anyway.

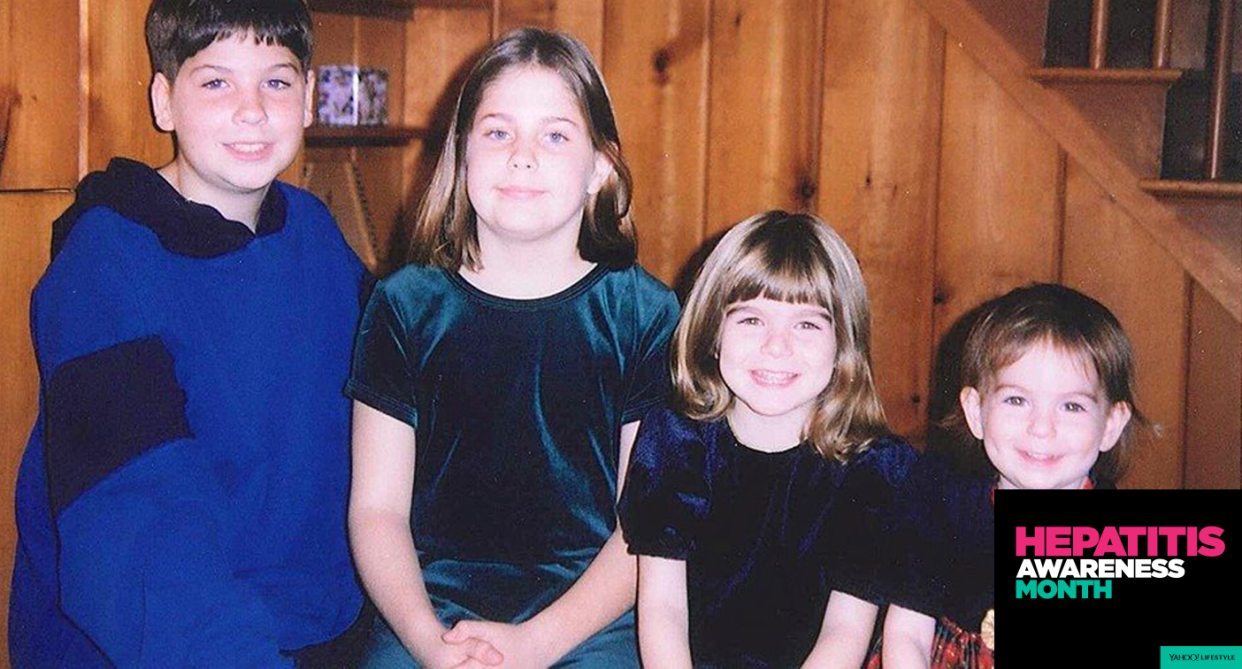

“Of the four of us, only two of us tested positive,” says Ventura. “I was 10 when I first was diagnosed, and my sister [who was also infected] was 3.”

Because Ventura’s mom was a health care practitioner, she was conscientious about teaching Ventura and her sister how to prevent them from infecting anyone else. “If we got cut, the person tending to it needed to wear gloves,” explains Ventura. “When I had my period, I had to reduce exposure.”

Since hepatitis C can be transmitted if you share a toothbrush or razor with an infected person, Ventura and her sister had to take certain precautions. “When I used toothpaste, I had to [apply it to] my finger instead of [directly on] my toothbrush. I’d have my own nail clipper kit. If I went and got a mani/pedi with my mom, I’d bring my own tools. She was very, very cautious, which I’m grateful for.”

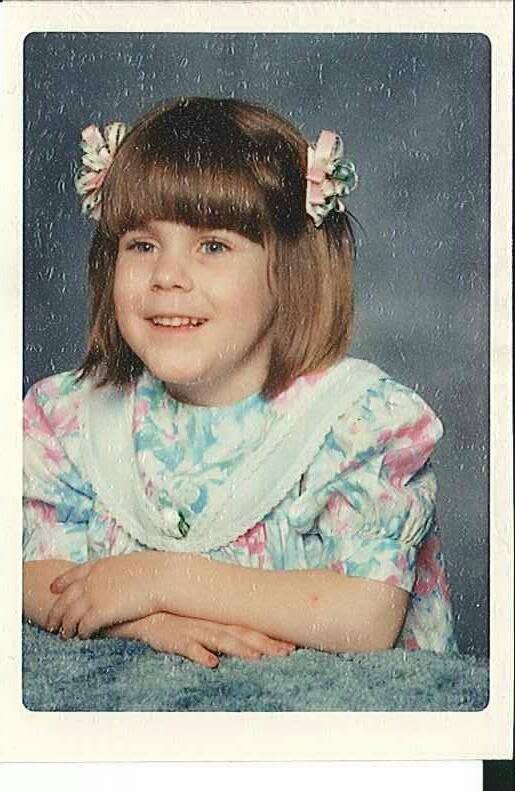

As a kid, however, there was an emotional burden to living this way. “I knew there was something wrong — I felt unclean,” she shares. “That I might make people sick. The way doctors would approach us like we were this interesting case study. But I wasn’t anything more than a little kid.”

The disease was also kept secret. “My mom made the decision she didn’t want anyone to know about it because of the stigma that exists, and fear and misunderstanding,” says Ventura, who lives outside of Boston. “She chose not to disclose it anywhere. We knew to be careful ourselves. So it was really a secret. Our youngest sister didn’t know for many years that we were sick, so it was really a secret in our own family.”

But the secret didn’t last long. In middle school, Ventura accidentally cut herself and went to the school nurse. “The nurse was trying to put a bandage on me without gloves and finally I came out and said I had hepatitis C,” she recalls. “Through the rumor mill, my small town found out.”

Because of the stigma of the disease, she ended up having to switch schools. “I grew up with these 80 kids my whole life and to not be around them anymore, it was hard,” she said. “From then on, I was very closed off about my hepatitis C. I was scared and fearful. The social stigma left a lasting impression of fear for anyone to find out.”

To monitor her health, liver function tests were a regular part of her life. Although these tests had always come back normal, that changed a week before Ventura’s 20th birthday. A liver biopsy revealed she had stage 3 fibrosis (fibrosis is when an inflamed liver starts to scar, replacing the healthy tissue and stemming the flow of blood to the liver, according to the American Liver Foundation).

“They said I’d be lucky to hit 30 without a transplant,” she says. “That was a real wakeup call. It was something on my radar, but never seemed like anything to worry about.”

In 2007, during her sophomore year of college, Ventura started taking the recommended prescription drug regimen available at the time (interferon and ribavirin) to cure her hepatitis — 6 pills a day every day for a year, plus weekly self-injections (her younger sister had started treatment at 14 years old). This caused serious side effects that took a toll, including nausea, vomiting, and excessive hair loss. “I would be in the shower and clumps of hair would fall out,” she recalls.

Rage was another byproduct of the medication. “I lost friends because of the way I was behaving,” she says. “I almost lost my job. It impacted me on many levels, emotionally and physically. I was just surviving. I wasn’t living. I’m thankful I had my mom to be there for me. But it was a hard year.”

A week before her 21st birthday, Ventura finished her treatment and was cleared of the virus. Ventura then realized that the symptoms she’d had for years, from severe itching she chalked up to dry skin to dark-colored urine she thought was from dehydration to fatigue she blamed on her heavy course load at school — not realizing they were all caused by hepatitis C — went away.

“That’s the danger of hepatitis C,” she notes, “even if you had symptoms, you wouldn’t think of them as symptoms of a deadly virus.”

For Ventura’s mom, after years of carrying the emotional burden of unknowingly infecting her children, having both of her daughters cured of hepatitis C was a huge relief. “She had always felt guilty for giving us the virus,” Ventura says. “Even though it wasn’t her fault. Post-treatment, I was elated for her that we were better.”

However, Ventura’s mother’s health then began to decline. Although her mom was able to take medication that finally got her hepatitis to undetectable levels, she was diagnosed with liver cancer. “She said, ‘Well, it’s a good thing,’” Ventura recalls. “She had cirrhosis for about a decade. Her score wasn’t high enough to get a transplant, so the liver cancer boosted her score.”

After waiting for 14 months for a liver transplant and watching her mother’s condition continue to worsen, the family finally got the call that there was a donor. Ventura’s mom received a liver transplant on May 1, 2014. “I never really knew how important the liver was until it stopped doing what it’s supposed to be doing,” Ventura says. “And I never appreciated how long she’d been sick until she wasn’t sick anymore.”

The 30-year-old continues: “It’s been a beautiful last couple of years knowing we’re all well and how easily cured [hepatitis C] is now. The treatment was scarier than the disease itself, and it’s not that way anymore. It’s simple, it works, and it has no side effects.”

After coping with family health issues that were kept secret for decades, Ventura decided to go public. Ventura, who works as the community outreach and education manager at the American Liver Foundation, started telling her story to others. “When I started sharing, kind of coming out of the closet with the disease, it was freeing and terrifying,” she says. “Now it’s becoming something that isn’t so taboo.”

She adds: “Only by starting the conversation can you break the stigma.”

May is Hepatitis Awareness Month. Read more about the disease on Yahoo Lifestyle:

The blood transfusion that saves my life gave me hepatitis C

Why baby boomers and veterans are more likely to have hepatitis C

Do you ever share toothbrushes? You could be exposing yourself to a disease

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.