Was Lucian Freud a bohemian rake or closet bourgeois?

At the start of the second, and final, instalment of his Lives of Lucian Freud, William Feaver suggests his predicament as a biographer. The volume picks up in 1968, with Freud in his mid-40s. Of course, the painter, in middle age, hardly conformed to a cocoa-and-slippers stereotype of domesticity. Yet his antic days were behind him, and he was increasingly concerned with his ambitions within painting. Things, as Freud’s Boswell puts it, were getting “serious”. How, then, to sustain interest when your material is less, well, colourful?

With a fight-picking, bed-hopping adventurer for a hero, Feaver’s rackety first volume, Youth, was highly entertaining. There were set-pieces – Freud’s childhood in Berlin, his stint as a Merchant Navy seaman during the war – while the locations were alternately glamorous (Poros, Paris, Ian Fleming’s hideaway in Jamaica) and seedy (the slum-like terraces of Fifties Paddington, where Freud had a studio). As quoted by Feaver, Freud played the mischievous bar-room raconteur, chuckling over bygone stunts and scrapes, and sticking the knife into old foes with venomous relish. His tongue-in-cheek working title for Feaver’s long-planned biography – The First Funny Art Book – rang true.

Volume two, aka Fame, is a very different beast. For much of it, Freud shuttles in his Bentley between studios in Holland Park, where he had a sound-proofed flat, and his 18th-century townhouse on Kensington Church Street. When he isn’t painting, pepped up by Solpadeine tablets, he’s out cruising for sitters. Inevitably, there are love affairs: the book opens with Freud clambering a drainpipe to woo Sixties It girl Jacquetta Eliot. Later, there are kiss-and-tell vignettes of this Casanova in old age. (One fly-by-night partner, an art student whom he whisked to New York by Concorde in 1997, used to call him “frisky biscuit”.)

Those sitters with whom Freud wasn’t physically intimate prove more memorable. The shaven-headed performance artist Leigh Bowery. His friend Sue Tilley (aka “Big Sue”), the subject of Benefits Supervisor Resting (1994), which sold at auction, in 2015, for £35 million. Kate Moss: “over-enthusiastic”, Freud recalled, though he agreed to tattoo swallows on her back. And, of course, the Queen, whom he painted, cussedly and bizarrely, as Feaver doesn’t say, as a dragged-up gangland bruiser, with a five o’clock shadow.

Great chunks of the book, though, are dominated by art-world politics, charting, for instance, the ups and downs of Freud’s relationships with various dealers, whom he tended to chuck if they failed to stump up sufficient cash. While it is interesting to be reminded of a time when Freud couldn’t secure a museum retrospective, anyone thirsty for tittle-tattle may put down this book still feeling parched. At one point, Feaver quotes Frank Auerbach – another Berlin-born painter, accustomed to scrutinising sitters, who became Freud’s closest artist friend after his thick-as-thieves rapport with Francis Bacon withered. (“She’s left me after all this time,” moaned Bacon, referring to Freud. “And she’s had all these children just to prove she’s not homosexual.”) For Auerbach, Freud’s bohemian reputation is a sideshow: “He was the most focused and unshowy and concentrated painter that you could possibly imagine.”

This is corroborated by Freud’s novelist daughter, Esther, who was surprised, when she sat for him (“It’s nice when you breed your own models,” the artist said), by how “organised” her father’s life had become. Above all, Freud valued punctuality in his sitters, ensuring that he could cram in as many as possible, day and night. (Sometimes he had nine paintings on the go.) If Youth revealed Freud to be a shameless social climber, Fame proclaims his acquisitive instinct, and preoccupation with money. He collected art (Corot, Degas, Rodin), loved fine tailoring, made porridge using mineral water, and indulged his whippet, Pluto, with prime mince from the posh butcher down the road. Perhaps, after all, Freud was – to adapt Bacon’s jibe – a closet bourgeois.

Thankfully, some of his devil-may-care waspishness, such a feature of volume one, remains on show: Charles Saatchi is “stupid”, while the critic Brian Sewell was “an arsehole with a bit of rouge on it”. As for his brother, Clement, with whom he feuded from boyhood, Freud’s final put-down is brutal: “We never got on. He’s dead now. Always was, actually.”

In general, though, the backbiting is kept to a minimum, and the tone is more reflective – with meandering musings about painting, presumably murmured down the phone at Feaver after Freud’s customary opening gambit (“Hello, Villiam, how goes it?”). (Freud’s confidante for decades, Feaver – who declined to sit for his friend but often visited to review a night’s work over a slap-up breakfast of woodcock or deep-fried parsley – made notes of their conversations, which provide his primary source.)

There are diverting details about Freud’s methods – mixing charcoal dust into his paint to give it, as Feaver puts it, a sufficiently “Paddington tinge”; tranquillising a laboratory rodent from Japan with champagne and sleeping pills before sittings for Naked Man with Rat (1977-78). But there are also repetitions and digressions that could be cut for a taut, new, single-volume version of this biography.

Ultimately, Feaver’s proximity to his subject is both strength and weakness. Because he quotes the artist so liberally, we get a vivid impression of Freud as a companion. But difficult aspects of his character (his enmity towards his mother, his monstrously casual approach to fatherhood) are insufficiently interrogated. Freud was obsessively private, and he was careful not to reveal to Feaver anything too touchy-feely. Feaver, for his part, reports but doesn’t judge – which is fine (they were friends, after all), but, after more than 1,100 pages, across both volumes, I longed for less neutrality and more personality from Feaver.

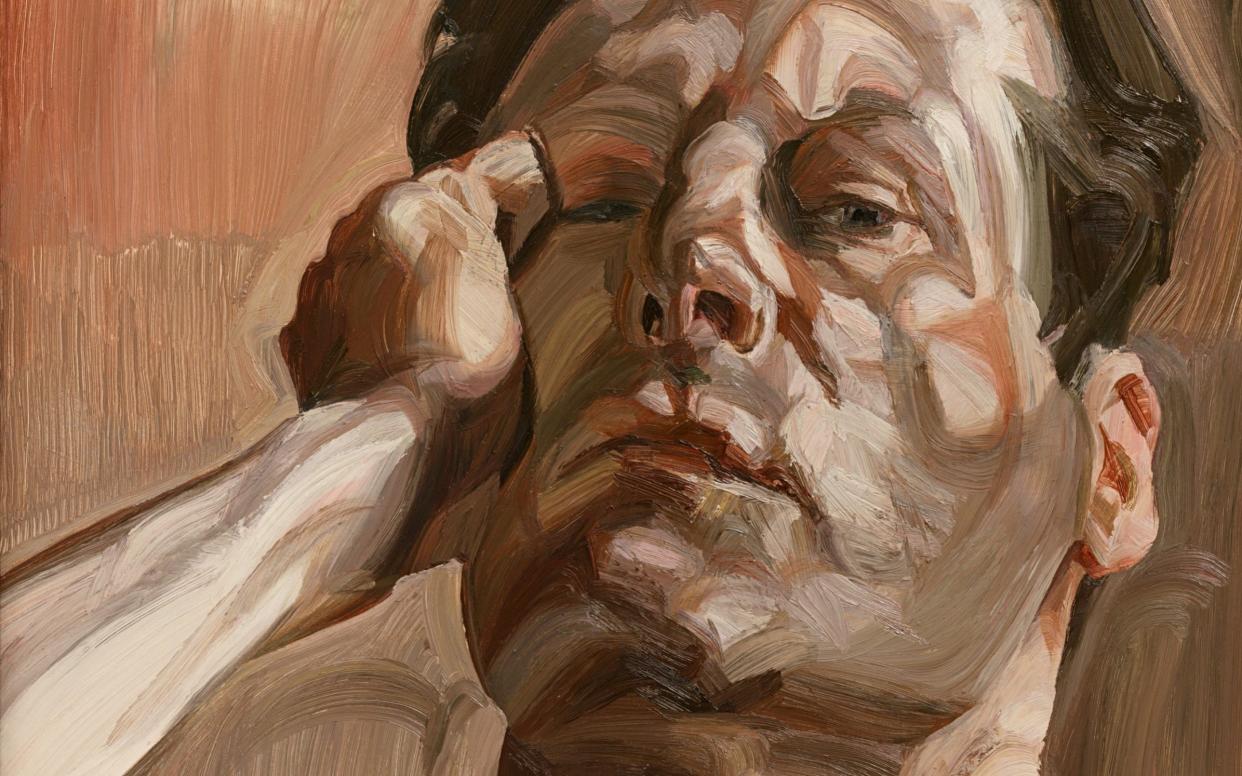

More analysis of the paintings, too: one of the joys of the first volume were Feaver’s intricate descriptions of individual canvases, such as Interior in Paddington (1951); in part two, such flourishes are strangely scarce. Freud’s greatness as a painter is taken as a given – but, because his approach (studio-based portraiture) was so old-fashioned, further examination of his achievements wouldn’t have gone amiss. Nine years on from the artist’s death, how should we think of Freud: as a sort of kitchen-sink Sargent, or something more profound? Feaver isn’t saying.

To order a copy for £30, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books